Credit score “migration” isn’t a new phenomenon. Scores for individual consumers rise and fall by definition. If someone gets behind on a loan, that counts against their score. If they apply for a lot of credit cards, that’s a hit, too. Keeping current on an account helps keep the score up.

The credit score system has been a basic of consumer credit for decades now, and the age of mobile phone apps for tracking scores has only heightened consumers’ own attention to these numbers. But in the last few years, unprecedented policy steps taken in response to the Covid pandemic shifted credit scores broadly — “migration” with a capital “M.”

Some key forms of credit went into “suspended animation” for a time. Mortgages became eligible for forbearance, federal student loan payments were suspended, and interest on those loans was reset to 0% for the duration. Direct stimulus payments helped consumers pay down debt.

Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Vericast’s 2024 Financial TrendWatch explores seven of today’s most critical financial services trends to provide a complete view of the current loyalty landscape.

Read More about Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

83% of FI leaders agree investing in AI is essential for 2024 but how you leverage AI is instrumental in success and meeting customer expectations.

Read More about Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

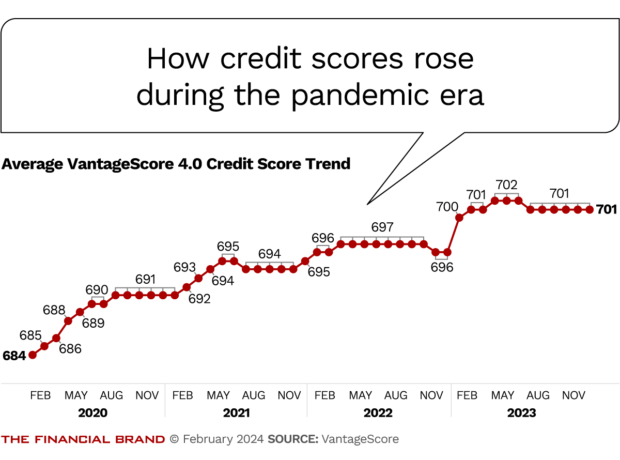

The net impact was an unprecedented increase in credit scores for many consumers, according to experts. According to VantageScore, average credit scores have been running at about 701 for six consecutive months since July 2023. (The maximum score is 850. The chart below shows the trend since the pandemic began.)

In June 2023, Rikard Bandebo, EVP and chief product officer at VantageScore, cautioned against an overreaction, calling credit score inflation a “dangerous myth.”

“It is erroneous to conflate the changes in median or average scores with the relationship between scores and the risk of default,” wrote Bandebo. He said that macroeconomic factors had to be considered:

“The risk of default for a given score will decrease during strong economic cycles and increase during weaker economic cycles.”

But others — among them, Capital One’s chairman and CEO, Richard Fairbank, — remain concerned. During Capital One’s yearend earnings call, Fairbank specifically used the term “grade inflation,” and said the bank had taken steps to not get drawn in by temporarily higher numbers.

What worries these commentators is that credit is being granted on the basis of scores that don’t accurately reflect the true risk of some consumers.

Read more: Auto Lenders Shift Gears in a Race to Outrun Covid Aftereffects

Do Credit Scores Mean What They Used to Mean?

And the distortion effect is not over yet.

With the exception of certain borrowers who qualify for special Biden administration relief efforts, payments on federal student loan payments have resumed, and interest is again accruing. But reporting of federal student loan defaults won’t begin again until the last part of 2024.

In 2023, the three primary credit bureaus also removed medical debt with an original balance of under $500 from credit reports and won’t gather such data in the future. And the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau started a rulemaking process in 2023 that aims to remove all medical debt from credit reporting. KFF — formerly known as the Kaiser Family Foundation — estimates that two out five consumers owe money for medical care.

Read more:

- How Alternative Consumer Credit Data Increasingly Supports Lending Decisions

- Why Headwinds from Deteriorating Auto Loans Will Whip Credit Unions in 2024

- Credit Card Watch: Balancing ‘Growth Math’ and Lending Risk

Concerns About Credit Score Trend Began in 2023

Ironically, the CFPB itself has raised alarms about ballooning credit scores.

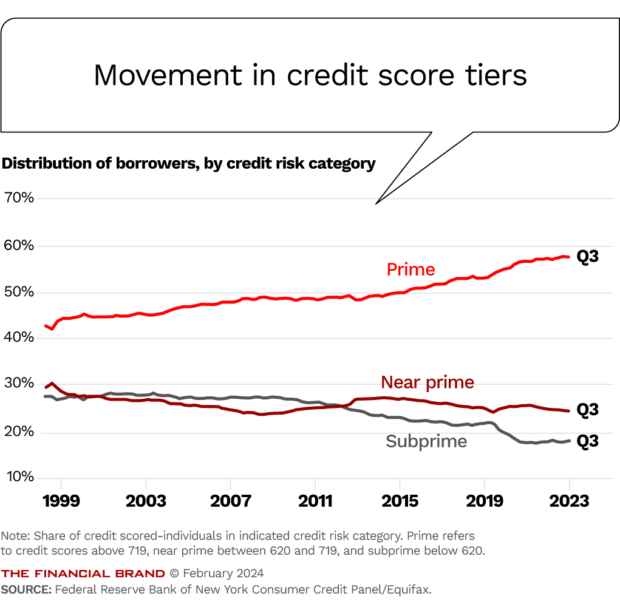

“We found that the deep subprime and subprime tiers experienced the biggest upward shift, though individuals in higher credit score tiers were also more likely to move up at least one tier than they were before the pandemic.”

— Consumer Financial Protection Bureau analysis

In July 2023 TransUnion noted that median credit scores had been rising during the pandemic and said its analysis had revealed that “some consumers who migrated to higher credit score ranges are becoming delinquent on their credit obligations at higher rates than historically observed for those risk tiers.”

In TransUnion’s yearend report, credit card delinquencies of 90+ days past due rose to 2.59% in the fourth quarter, the highest level since the 1.3% seen in the final quarter of 2020.

Some lenders appear to be adjusting. TransUnion noted that nonprime card issuances were down year over year in the third quarter, falling to 20.1 million new card accounts versus 21.6 million in 2022. (TransUnion reports originations of card accounts one quarter in arrears.)

This was a departure from the usual behavior at that point in the year. “We will be carefully watching to see if typical seasonal patterns will return based on liquidity events, such as tax returns and annual wage growth,” said Paul Siegfried, SVP and credit card business leader at TransUnion.

Read more: Credit Card Trends Have Bank Issuers on Alert

Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Achieve a better return on your marketing investment. Leverage behavioral data and analytics to target the right customers with the best possible offers.

Read More about Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Instant Messaging. Instant Impact.

Connect with your customers and provide lightning-fast support as effortlessly as texting friends. Two-way SMS text messaging is no longer optional.

Federal Reserve Study Probes Subprime Shifts in Card and Auto

Now a new staff study from the Federal Reserve, published in mid-January 2024, found that many consumers benefited from the movement between credit tiers during and after the pandemic.

“Many consumers saw an increase in their credit scores sufficient to move out of the subprime category, and the share of borrowers with subprime scores decreased to the lowest level seen since the late 1990s.”

— Federal Reserve staff study

But this migration also muddied delinquency analysis, particularly among borrowers who remained in subprime categories. The report noted that delinquency levels had risen in both auto lending and credit cards among subprime borrowers — in the case of vehicles, to its highest level since 2000.

The research, using simulations, suggests that part of that trend reflects the “graduation” of some consumers out of subprime: “Because so much of the increase in subprime delinquency rates owes to this migration, the large increases in these rates should not be used as a sole indicator of deteriorating credit quality.”