A source of angst for neobank creators and the investors who back them may suggest a potentially successful strategic direction for traditional institutions large and small that are willing to double down on neobanks’ blueprint and create their own alternative providers.

In fact, consulting firm Simon-Kucher says that one out of three neobanks being formed now already have an incumbent bank or a larger financial services organization as their parent. The firm expects this trend to not only continue, but potentially accelerate.

In a sense this amounts to things coming full circle, with traditional institutions disrupting the startups that disrupted them. And they are doing so with advantages that most neobanks have not had.

Perhaps more significantly the trend also means that traditional institutions increasingly are disrupting their own industry from within.

Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Vericast’s 2024 Financial TrendWatch explores seven of today’s most critical financial services trends to provide a complete view of the current loyalty landscape.

Read More about Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

83% of FI leaders agree investing in AI is essential for 2024 but how you leverage AI is instrumental in success and meeting customer expectations.

Read More about Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

How Traditional Banks’ Place Versus Fintech Neobanks is Shifting

The term used for these new-age neobanks is “speedboat.” The idea is that traditional banks face multiple legacy factors keeping them from serving businesses or consumers with fresh ideas, including their sheer size in the case of the largest banking players. However, a newly created speedboat built to serve a specific market niche can enjoy an agility that few banking institutions would otherwise have approaching that niche in traditional ways.

Christoph Stegmeier, Senior Partner at Simon-Kucher, distinguishes between the two subvarieties of neobanks in this way:

Nonbank Neobanks are “the garage startups, the smaller players, who have the initial pioneers like Revolut and N26 as their models.” They find a model, generally built around solving pain points in traditional institution processes, raise venture capital and work to scale up. Simon-Kucher estimates that few among the 85 U.S. neobanks in this category are breaking even.

“Many of these founders are not bankers, and that’s why they focus a lot on user experience,” says Stegmeier. “But very few of them actually have a deeper understanding of financial services and where money is made.”

Banks’ “Speedboats” have chiefly been formed by larger banking parents. Among the examples around the world that Stegmeier cites are Chase, the digital banking brand JPMorgan Chase started in September 2021 in the United Kingdom. Others include Liv, from Emirates NBD, Bancolombia’s Nequi, and Deutsche Bank’s Fyrst.

Such “bank neobanks” get a slug of funding from the parent, rather than having to continually pitch to investors. “Prove to us that you can be successful in your early stages,” Stegmeier says the parents tell the speedboats. “If you’re successful, we’ll give you more money to spend and grow.”

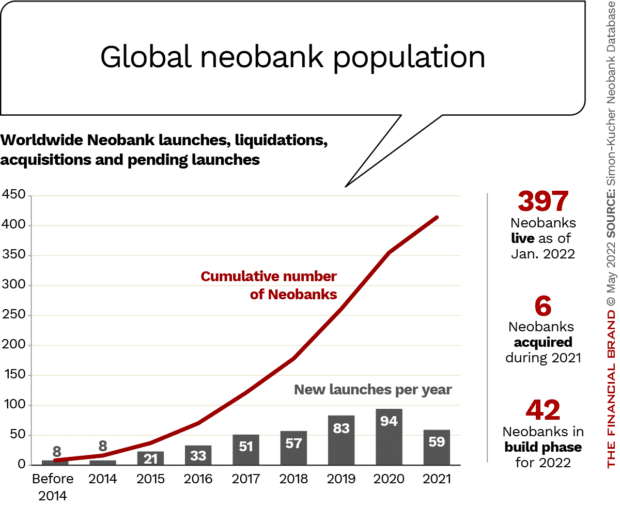

The world’s population of neobanks stands at roughly 400 players at different points in their lifecycles. Simon-Kucher analysis indicates that out of the top 25 neobanks around the world only two have reached profitability. Most earn less than $30 in annual revenues per customer.

“Out of the 400 or so neobanks, there are at least 300 that will not be around for too long.”

— Christoph Stegmeier, Simon-Kucher

Read More:

- Four Strategic Lessons from Digital-Only Banks and Neobanks

- The World’s Biggest List of Digital Banks

- Digital Bank & Fintech Slogans: 200+ Taglines from Around the World

- 5 Popular Fintech App Features Banks Should Add to Mobile Banking

Why Starting a Neobank May Be a Good Strategy for Banks

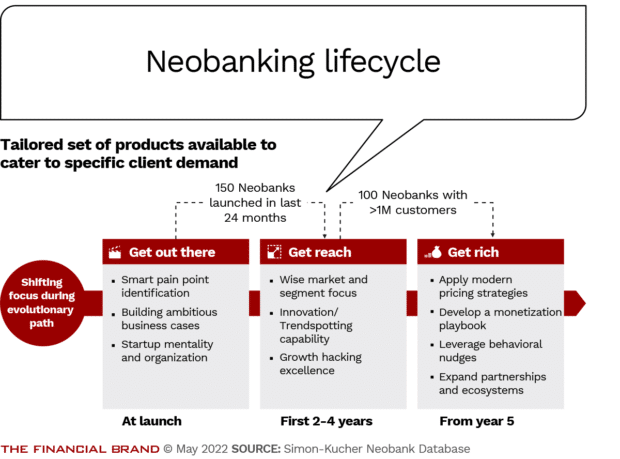

Bank-originated neobanks can serve as “digital attackers,” according to Stegmeier. The firm sees the neobank movement overall going beyond the early idea of bringing digital user experience to consumer banking. Now the emphasis is on serving market niches, such as creators (artists, writers, etc.) or ethnic communities, or, like the Chase effort mentioned earlier, attacking new geographic territory digitally.

Stegmeier says that some bank-originated neobanks may represent learning experiments or incubators for new ideas and innovations. An example of the latter, he says, is Santander Bank’s Openbank, which is being used to launch a buy now, pay later offering in Germany.

Getting started with a bank neobank means capital, but how much is needed depends on the target market and the goal. Stegmeier says he has seen new neobanks started for as little as $5 million from the parent, but some have been as high as $500 million or more.

The basic technology to get a neobank going is no longer the uphill climb it once was. “In most countries you now have almost plug and play solutions for starting a new neobank, so hardly anybody builds that themselves,” he explains. “Specialized providers will help you set it up.” (Among such players are Synctera, Treasury Prime, Synapse, Rize and Nymbus.)

The human factor remains a key challenge, assembling the proper team. Typically bank-originated neobanks get going with a blend of bankers from the parent organization as well as outsiders who bring other skills to the new effort.

Fresh Thinking Takes New Faces:

Banks have found that using the same people, working in the same building, as the original institution produces a neobank that looks almost exactly the same as the traditional parent.

Stegmeier adds that career bankers typically can’t spot the pain points of banking as readily as do industry outsiders. They’re too much of the traditional system. However, some traditional expertise is actually a competitive edge with a new venture. Think of it as the mentorship that the typical neobank has not had.

“Most startup players do not have any lending business and its difficult to make money in banking without a balance sheet,” says Stegmeier. Neobanks that begin inside a bank have the institutional lending experience and understanding to lean on and the charter or license permitting them to be a lender, typically with the advantage of raising relatively cheap deposits.

As a result of these advantages, neobanks with bank parentage tend to reach breakeven faster than fintech neobanks. Stegmeier notes that while there haven’t been many neobanks launched by smaller institutions, “we think this is a clear opportunity for a community bank.” However, he adds that smaller banks must know precisely what they are trying to do with a neobank strategy and who they are trying to reach and serve with it.

Stegmeier says that some regional banks and co-operative banks in Germany have created small neobanks with a focus on one or two products that the parent is very good at. They seek to use the neobank as a way of building a broader base for that specialty.

“I call this approach the ‘piranha strategy’,” says Stegmeier. “I think it could play a very interesting role in the U.S.”

Examples of smaller institutions’ forays into neobanking in the U.S. include BankDora (actually part of a credit union), Monifi and BankMD.

Read More: Neobanks’ Growth Comes at a Cost: What it Means for Traditional Banks

Looking into Future of ‘Traditional Neobanks’

Stegmeier says the potential for “inside investors” will feed the trend towards the bank-originated neobank strategy. By contrast, investors in fintech neobanks increasingly “are starting to ask questions about why we aren’t making any money?”

Neobanks have also been called “challenger banks,” and they will have a peculiar challenge of their own in the economy of 2022 and beyond.

Part of the reason that so few neobanks turn a profit is that they give nearly everything away, at least initially and at the most basic levels. Those with payment elements have interchange income, or a least a piece of it, through banking as a service arrangements. But Stegmeier says that for many neobanks the key to profitability is “the need to move from ‘free’ to ‘fee’.”

The challenge is to upsell account holders to a for-pay level of the neobank’s service. However, Stegmeier points out that consumer-oriented neobanks generally don’t serve the affluent. More typically they serve mainstream consumers, or even young people and the underbanked.

“Many of them are being hit quite hard by inflation,” says Stegmeier. Upgrading people to paid product levels is going to be harder when inflation causes more people to struggle.

However, inflation has another side that may help fintech neobanks: consumers’ quest for return.

“As inflation increases, consumers are going to feel that they need to invest differently, rather than just having their money lying around,” says Stegmeier. He says the U.S. fintech neobank fraternity is well established in this area, with the likes of Acorns and Robinhood. Other neobanks will jump on that increased appetite for return, “and they’ll make savings and investments one of their key priorities.”

Neobanks backed by banks, with the direct ability to offer insured high-rate deposits, will enjoy an advantage too. However, with a few exceptions, Stegmeier doesn’t see direct banks as competitors to neobanks.

“Neobanks are trying to do things very differently to disrupt traditional banking,” Stegmeier explains. “A direct bank doesn’t really disrupt except, maybe, on price. I’m not sure there is enough innovation or agility in the direct banks to move towards the neobank. They might come a bit closer, but I don’t see them coming together with neobanks.”

Read More: 8 Fintech Trends Changing Banking Forever

Instant Messaging. Instant Impact.

Connect with your customers and provide lightning-fast support as effortlessly as texting friends. Two-way SMS text messaging is no longer optional.

The unfair advantage for financial brands.

Offering aggressive financial marketing strategies custom-built for leaders looking to redefine industry norms and establish market dominance.

4 Key Elements for Building a Neobank ‘Speedboat’

For both fintech and bank-launched neobanks, Stegmeier outlined four activities that Simon-Kucher considers “must-haves” to boost profits. The rationales that follow each are from the firm’s study:

• Buy now, pay later as embedded financing. “It can be easily embedded into a neobank’s core offering. It’s a booming market, and presents little price sensitivity for clients.”

• Digital and hybrid investments. “One of the most profitable digital banking products — rapidly increasing customer base among digital natives.”

• Cryptocurrencies. “High-margin products. It’s a quickly growing market with many first-time users and is gaining increasing attention from larger banks.”

• Digital mortgages. “There’s a lack of truly digital solutions in this space. It provides access to profitable customer segments.”

Some of these elements may not be comfortable for bankers, such as crypto. However, Stegmeier says it is important to think in terms of potential growth.