Once annually, in late September, FDIC releases branch level deposit data in its Summary of Deposits database. Due to COVID-19 restrictions and shutdowns there were general expectations that the data would show a staggering increase in branch closures, but that large decline in the number of branches didn’t occur … at least not yet.

I wrote about this data earlier on The Financial Brand, explaining that not only was there only a modest increase in closures, there was a large increase in the number of new branches opened. Pretty startling for all those industry experts touting the death of the branch channel.

But digging deeper there were even more insights that could be gleaned for this unique data set. Here are four hypotheses coming out of the data and what could finally be made of them:

The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Learn how to enhance your brand’s local visibility, generate more leads, and attract more customers, all while adhering to industry regulations and compliance.

Read More about The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

Build a modern credit card strategy that balances profitability and risk, adopts the latest technology and delivers the customization that cardholders demand.

Read More about Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

1. Hypothesis: It’s Chiefly Megabanks That Are Closing Branches.

Reality: Mostly true.

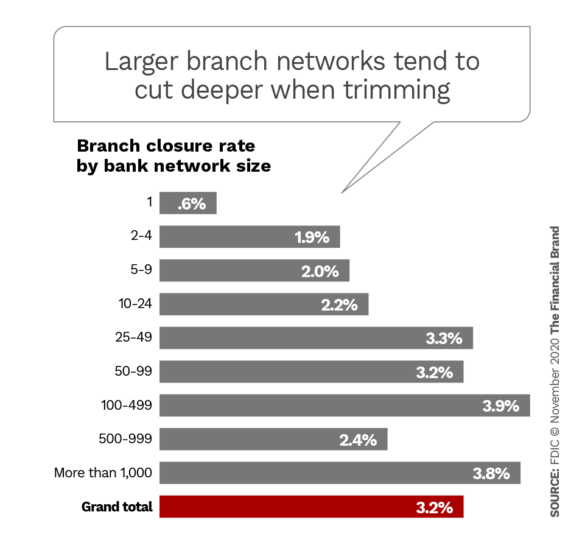

Branch closures are occurring at all branch network sizes but they do tend to skew higher among larger banks.

However, there’s an exception. The largest regional bank branch networks, between 500-999 branches, closed fewer branches proportionately than most groups. In fact, that group closed branches at only three-quarters of the rate of the industry in whole.

In past articles I’ve mentioned that the continued consumer behavioral shift to digital channels has been reducing the number of branch transactions for years. The less frequently you interact with a retailer, the farther you’re willing to travel to do that transaction. This phenomenon not only fits retail distribution theory but has been proven repeatedly in real life studies in my experience.

Read More: Branches Still Dominate, But Banks Won’t Need as Many to Compete

2. Hypothesis: Small-town America Will Soon Be Unbanked As Branch Closures Are Concentrated In These Smaller Towns.

Branches outside of Metropolitan Statistical Areas serve small-town America. By definition, those communities have smaller population bases and are more rural than more urban areas. With limited opportunity, surely branch closures would be concentrated there.

Reality: False.

About one in six branches today are located outside MSAs. Yet, these rural branches only represent 11% (one in nine) of branch closures in the last year. These smaller towns across the country are more lightly banked today with few communities having multiple branches of the same bank. Closing a branch means exiting that town so banks may consider that a significant barrier.

Read More: Trimming Branch Networks? Many Banks Find It Tough

3. Hypothesis: In-Store and Supermarket Branches Are Going Away Because They Are Unprofitable.

Reality: True.

The number of supermarket bank branches does continue to decline. Ten years ago, there were about 5,000 bank branches in supermarkets. Today there are about 4,000 — about 5% of total bank branches.

The count for these types of bank branches peaked in the late 1990s and has been steady decline ever since.

The rational for closing these sites is that the small space does not allow enough staffing to drive enough account acquisition to fuel long-term growth.

In the latest closure data, nearly 11% of branch closures are supermarket branches. They averaged only $22 million in deposits. They are going away at a faster rate than traditional branches, but are still likely to be around for years to come.

Read More: Rethinking Branch Networks Without Killing Sales or Growth

4. Hypothesis: Only Unprofitable Branches Are Being Closed.

Unprofitable branches need to be reviewed to determine the cause for the issue. Perhaps it’s a limited-opportunity market, or a poor location or site. Perhaps it’s because the office is over-staffed. On the other hand, perhaps it’s simply that these branches are new and haven’t yet built a mature customer base.

Reality: False.

The prior-year deposit base of those branches closed in the last year averaged $50 million in deposits. Given current net interest margins and fee income those branches averaged around $1.5 million in revenues. With average branch operating expenses less than $1 million annually the average branch closed was likely profitable.

And this isn’t a shock when you consider the history: In my many years in the branch distribution space, most of the 2,000+ branches I closed were profitable. In fact, many generated net incomes of $1 million or more.

The reason we closed them was that we could get away with the closing and not lose customers.

When you have the right data and analytics to study your branches, so that you can accurately predict what will happen upon a branch closure, you can make more surgical, targeted trims. We found that you could take the brick and mortar costs out and reassign the staff to other sites, saving about half of total branch expenses. The key was being able to keep nearly all the customers (96% in my experience), and most importantly nearly all the sales opportunities the closed branch captured (90%+).