How can marketing, advertising, and fresh new takes on retail banking strategy improve financial life for Americans? Top officers from three banks — Colorado’s FirstBank, direct bank Ally, and Umpqua Bank — gave The Financial Brand Forum attendees perspectives on new ideas can rejuvenate traditional banking services.

All three banks’ efforts, in different ways, came about by scrutinizing the role of money and banking in consumers’ lives.

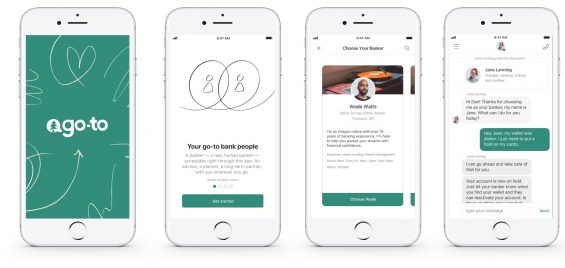

Umpqua Bank took the opportunity of the event to break the news that it was expanding its Go-To program, which pairs every Umpqua consumer customer with a human personal banking officer who is reachable for extended hours via a special app. Now Umpqua will let prospective customers request a Go-To personal banker as well.

Rilla Delorier, EVP and Chief Strategy Officer at Umpqua Bank, told The Financial Brand the bank will promote the Go-To feature to consumer prospects with an advertising and marketing program with a record-setting budget. This will include paid social media advertising. Delorier says that a small test of the prospect outreach via Facebook far exceeded the bank’s expectations.

Why Industry Cloud for Banking?

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking helps deliver personalized products and services that today’s customers expect.

Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

Build a modern credit card strategy that balances profitability and risk, adopts the latest technology and delivers the customization that cardholders demand.

Read More about Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

Maybe Too Little Friction Isn’t Good Either

The battle cry of the banking disruptor has long been “Reduce friction!” The idea is that the classic ways of handling banking affairs are full of pain points, unnecessary roadblocks, frustrating delays, postponed gratification, and more.

The unspoken implication: friction is a human factor — evolve the human banker out of the process and you eliminate the friction.

Almost heretically, at least in some circles, Rilla Delorier speculates that maybe money matters can grow too smooth.

“Money is a huge type of friction,” says Delorier. “What besides money complicates your life more? It deserves a little friction, a little consideration.”

Many Americans live paycheck to paycheck and are “financially fragile,” according to Delorier. This argues that something is missing, that they seem less than financially astute in many ways.

“People are over-banked and under-served,” says Delorier. Too many people make financial missteps — missing mortgage payments or falling behind on bills, for example — for anyone to think they are on such solid ground that they don’t need help. Many today put their hope in tools such as apps built on artificial intelligence, But Delorier says Umpqua believes that what is often missing from consumers’ banking relationships is … a banker.

“What customers care about is their money, and making the most of what they have, and sometimes they need help with that, and not self-service help,” Delorier says. “They need an old-fashioned bank person — a human. Somebody who knows them, understands their needs, who has experience and expertise, someone who can guide them.”

“Consumers don’t give a damn about our strategy,” says Delorier. To consumers, she continues, it’s just about their money.”

As a result, Umpqua has shifted its focus from channel thinking to thinking about “Human-Digital,” keeping humans at the center, and using technology to make it easier to assist people.

This program, launched in 2018, lets every consumer doing business with Umpqua select a personal banker from online rosters. (Delorier says that once a banker has reached 800-1,000 consumers, they are taken off the menu to allow them to concentrate on that following.) Technology in the form of the bank’s “Go-To” app facilitates communication and advice between banker and consumer.

“It’s the democratization of private banking,” says Delorier. While personal bankers are not available 24/7, Delorier says Umpqua is examining how to provide help when the consumer’s prime contact is off … or sleeping.

Read More:

- Secret To Digital Banking Success is AI With ‘Human-Like’ Feel

- Exceptional Customer Experiences Depend On More Than Data Alone

FirstBank: Add Humor and Humanity to Marketing Mix

While financial institutions have loosened up somewhat in recent years, the use of humor and offbeat promotions remains atypical. Heck, many banking brands bend over backward to avoid the color red in logos and other brand materials lest anyone think that the pigment came from their bottom line. Colorado’s FirstBank fit the usual mold up until about 2009, according to Jim Reuter, CEO and President. Its marketing was “very straightforward and down the middle.” In that year the bank engaged a new agency, TDA_Boulder, to bring it a fresh look and feel.

The agency, which continues to serve FirstBank, came up with some very different ideas.

“We said no to 50% of them,” Reuter recalls, “because, we said, ‘We’re a bank and we can’t do that.’ But eventually we got our courage up and took a little more risk.”

The timing of the shift to use more humor and more personality and humanity in the bank’s marketing wasn’t random. In 2009, as recovery from the Great Recession was just beginning, “it didn’t hurt to make your brand look more human,” says Reuter.

Today, FirstBank is known for wry advertising. For example, commercials launched in spring 2019 had the common theme of “customer service that’s almost too good to believe.” To illustrate that, the spots use three situations: a husband who greets his wife at the door, having been turned into a hedgehog by a witch; another wife greeted by a husband skimming their pool, while walking on water; and a neighbor watching the guy next door being beamed aboard a UFO.

The unbelievable thing in each spot is not the obvious, but that the wives and the neighbor have all received really good service at FirstBank. A FirstBank spot promoting Zelle admonished viewers to “pay your friends back, before they pay you back.” Payback examples included having one’s office filled with live chickens and a hair dryer being rigged as a smoke generator.

Another campaign featured scenes shot in the style of glamour magazines that actually illustrate ways that young people could save money. These steps included using parent’s TV logins, cutting one’s own hair, and making coffee at home instead of ordering high-priced brews at a trendy chain.

Reuter notes that the bank’s atypical marketing isn’t just about driving profits by tickling financial funny bones. The savings spots, for example, make a larger point.

“Millennials are actually very good savers,” says Reuter. “The reason they get a bad rap is because they don’t buy things — they save for experiences. We all think that because they don’t buy cars or houses as soon as other generations did that means that they’re bad at savings. We thought this campaign was a great way to make savings cool.”

FirstBank’s marketing has gone beyond traditional media and beyond advertising. The bank teamed up with the Copper Mountain ski resort for a sort of treasure hunt, called “Capture the Cube.” Orange cubes patterned after the FirstBank logo were hidden throughout the resort. Skiers and snowboarders who discovered them won their choice of limited edition designer skis and snowboards.

Reuter grumbled that one multi-time winner appeared to have an edge — “I think he had some friends who worked on the Copper Mountain ski patrol” — but when he asked if he could present one of his prizes to his girlfriend on camera, the bank went along. He sprung a surprise on both the woman and the bank: He knelt and popped the question. The social media payoff encouraged the pleased bank to pay for the bride’s wedding dress. That gesture goosed the social media pickup even further.

The cube promotion proved popular and was repeated. As time went on, the bank adopted other unusual efforts that built repeat efforts. One is “Colorado Gives Day.” In this program, on a designated day the bank publishes a list of hundreds of charities on the Coloradogives.org website. Consumers are encouraged to visit the site and make a donation to the cause of their choice, and the bank pledges an incentive boost to all donations made that day. The first year that the bank tried this, it aimed for a $1 million fundraising target. $8 million was raised. To date, Reuter says, $217 million has been raised, including $35 million in 2018 alone.

The cube promotion proved popular and was repeated. As time went on, the bank adopted other unusual efforts that built repeat efforts. One is “Colorado Gives Day.” In this program, on a designated day the bank publishes a list of hundreds of charities on the Coloradogives.org website. Consumers are encouraged to visit the site and make a donation to the cause of their choice, and the bank pledges an incentive boost to all donations made that day. The first year that the bank tried this, it aimed for a $1 million fundraising target. $8 million was raised. To date, Reuter says, $217 million has been raised, including $35 million in 2018 alone.

“Show, don’t tell people that your bank cares,” says Reuter.

“At the end of the day, we’re in business to make money,” says Reuter of the privately held bank. Reuter believes the change in the bank’s public personality has paid off. It’s seen a decade of record earnings, he says, in addition to which deposits increased 38% from the end of 2013 to the end of 2018.

Ally Bank: More than a One-Trick Pony

Two little girls are sitting at a kiddie table with a bankerly man joining them. He asks if they would like a pony. The first girl says she would, and receives a small toy pony. The second girl also says yes, and the banker nickers softly. From off camera wanders in a live, saddled pony for the second girl. She is understandably quite pleased.

The first girl looks at her now-disappointing toy. “You didn’t say I could have a real one!” she objects.

“You didn’t ask,” the banker deadpans.

The first girl looks on in disbelief and a trace of anger.

“Even kids know it’s wrong to hold out on somebody. Why don’t banks?” the voiceover asks. The spot goes on to describe Ally’s “Sleeping Money Alerts,” designed to let consumers know if they could be putting their deposits into higher earning accounts.

This was one of the first ads run by Ally Bank, a decade ago, as it began transitioning from its roots as GMAC.

“How can we solve the pain points? How can we solve the things that we don’t like as customers?” was the fledgling bank’s mantra, according to Andrea Brimmer, Chief Marketing and P.R. Officer at Ally.

“We’re in an industry that has a extreme amount of data,” says Brimmer, “and that’s a good thing. But sometimes this makes us see people as ‘spots and dots.’ 70% of consumers tell us they want to make an emotional connection to your brand. How do you reconcile these two things?”

From the get-go, Brimmer says, Ally has tried to focus on the consumer, with a square deal and elimination of bothersome elements found with other banking companies. All of this has been done in a completely digital approach to financial services.

“A lot of brands are scrambling to get to where we’re at,” says Brimmer. She says the “pony” ad put Ally on the map, and the marketing team has worked to continue putting the direct bank’s best efforts forward.

“As marketers, it’s our job to make sure people care,” Brimmer says. This has grown more important as competition continues to grow, coming from many traditional as well as new directions.

Read More:

- Why Ally Bank’s CMO is Really Their ‘Chief Disruption Officer’

- How Ally Bank Unified The Online, Mobile and Tablet Experience

Brimmer says Ally tries to frame its branding in three facets: incite, improve, and inspire.

Inciting, Brimmer says, means showing what’s wrong with the business that Ally can address.

Improving includes all the efforts to make such intentions a reality.

Inspiring means waking more Americans up to what they aren’t typically getting from financial institutions. One example is the bank’s “payback time” campaign of 2018, which stressed how many millions in lost interest people leave on the table by not being guided to the best earnings opportunities for their deposits.

One of the bank’s most recent efforts has been to encourage consumers to think more deeply about their financial choices. This is the bank’s ongoing 2019 campaign urging consumers to use the various published ratings of financial providers to make more educated decisions about providers. (Ally, naturally, scores well.)

Right at the time of The Financial Brand Forum, the bank was surprising selected consumers with gift deposits making up for their tax payments. This program, “Reverse Tax Day,” follows last year’s “Banksgiving” promotion, in which Ally call center workers were empowered to give cash gifts, including large amounts of cash, in some cases, to consumers they assisted.

While helping consumers, these campaigns also have a payoff for Ally. She points out that the “payback time” promotion enabled the bank to open over 71,000 accounts in two weeks, making October 2018 the best in the bank’s history. Brand awareness for Ally continues to grow as a result of its pro-consumer projects and campaigns. Brimmer says this was a tipping point, with volume spiking but not leveling off once the campaign was over. More broadly, she adds, research has found that these efforts have established Ally in the eyes of the public as a consistently consumer-centric brand.