Alyson Clarke recently received two birthday emails. One came from her bank, essentially saying, “Hi Alyson! Happy Birthday!” End of message. The other came from a container store that she’s shopped at before. The retailer not only gave her birthday greetings but also presented her with a special birthday offer tailored to her shopping history — in this case the store offered savings on shoe storage boxes, something she’s bought before.

Clarke says her bank’s message just barely merited a shrug. The container store offer at caught her attention.

“Getting a simple ‘happy birthday’ from your bank is not personalization,” says Clarke, Principal Analyst at Forrester Research. She says that her bank knows much more about her than the container store does, yet the birthday message from the store meant much more than the bank’s.

“There are so many ways to see what’s important to me,” says Clarke. “Instead, all I got was ‘Happy Birthday’.”

The need to do better than that has been widely recognized. A Harvard Business Review report states that “many organizations across industries are already investing in this area, and reaping the rewards. When executed effectively, strategic personalization initiatives, can drive significant revenue impact … fostering greater customer loyalty and retention.”

While most banks and credit unions recognize the value of personalization, however, they lag in building the capability. Less than 10% of the industry has actually deployed advanced personalization technology, according to the Digital Banking Report.

In fact, the rallying cry of “personalization” drives lots of missteps, according to Clarke. Sending reminders to the deceased is one example — how well does the institution really know that consumer? (The opposite — being told by a credit union teller that records indicate that one is dead — is irritating “non-personalization,” as well.)

The truth is that simply stamping a consumer’s name at the top of a message means very little, no more than would sewing one’s name in an off-the-rack garment make it “tailored.”

As Clarke defines it, “Personalization is an experience that uses customer data and understanding to frame, guide, extend, and enhance interactions based on that person’s history, preferences, context, and intent.”

Ultimately, “personalization means adding value,” says Clarke. “If you’re not doing that, you aren’t really personalizing.”

At The Financial Brand Forum and in a subsequent interview Clarke spoke about personalization efforts that really work versus common errors. She also discussed nearly a dozen real examples of financial institutions that have been getting personalization and innovation right.

The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Learn how to enhance your brand’s local visibility, generate more leads, and attract more customers, all while adhering to industry regulations and compliance.

Read More about The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Instant Messaging. Instant Impact.

Connect with your customers and provide lightning-fast support as effortlessly as texting friends. Two-way SMS text messaging is no longer optional.

Personalization in Banking Means Tossing Out the Sales Mentality

Since the Wells Fargo sales scandals, some banking institutions will twist their terminology like a Bavarian pretzel to avoid using the words “cross selling.” Sometimes terms like “personalization” and “consumer-centricity” get co-opted to sound like benevolent alternatives to the out-of-favor term.

“Every time I hear bankers say they want to make the ‘next best offer,’ I cringe.”

— Alyson Clarke, Forester

“Every time I hear a banker say that they want to make the ‘next best offer,’ I cringe,” says Clarke. The usual meaning of “next best offer” is, “The consumer bought the first product offered, so what’s the next good fit on our shelf for them?”

That is a sales-oriented viewpoint, Clarke maintains.

“‘Next best offer’ to me means personalization on the bank’s terms, not the consumer’s,” says Clarke. “It’s pretty much like, ‘Do you want fries with that?’ That’s not really personalization at all.” It’s still a way of thinking how to close another sale, which may or may not be in the consumer’s interest, and she maintains that that’s not personalization.

Clarke says thinking in terms of the “next best interaction” makes a much better way of looking at a consumer relationship, because it implies a consultative, communicative role that may not result in a sale.

For Clarke, personalization entails knowing the consumer sufficiently well that the bank or credit union has earned the right to take a conversation to the next step. She compares the true personalization relationship to dating. The two parties ideally build a relationship in the process of learning more about each other.

Just as true courtship takes time, Clarke believes banks and credit unions must avoid rushing personalization. “Too many firms check off the box on delivering ‘personal’ experiences too quickly,” she says, resulting in sometimes awkward messages. Assuming too much familiarity when the institution and the consumer haven’t done much business is one example.

Most banks and credit unions are not rushing, however. The opposite of awkwardness is the institution that, having learned some key points about a person, fails to account for them in communication. In addition, having one or two data points about a consumer and extrapolating an entire view from that is dumb. After all, “two fuzzy ears, sharp teeth,” may describe a white mouse, a puppy, or a grizzly bear.

Using data to determine what to ask about next, rather than as a guide to a “next best offer,” keeps the learning in the process, Clarke states.

Read More:

- Crafting Amazon-Like Banking Experiences Easier Said Than Done

- 5 Tips For Financial Marketers to Tap AI’s Personalization Potential

Think ‘Curation’ Instead of ‘Offers’

There are ways to enable consumers to bring their own choices to the table that financial institutions can learn from, according to Clarke.

Any cab or ride-hail customer who has suffered through their driver’s love for heavy metal, for example, should appreciate Uber’s “Your Ride, Your Music” service, which allows the consumer to select from their Pandora or Spotify account to play on the car’s speakers.

Clarke says that Airbnb improves personalization by recommending sites of interest, restaurants, and more near the accommodations it rents to consumers. These are filtered based on what the company knows about the consumer, but are not thrust on them.

“Airbnb curates content based on what it knows of you and how you like to travel,” she explains. “For most banks, offers are still one size fits all.”

In fact, Clarke thinks banks and credit unions need to move beyond the concept of “offers” and adapt more of a “curated” viewpoint in bringing options to consumers — stop thinking from the bank’s perspective, in other words.

Clarke thinks that institutions attempting to adopt personalization must think more broadly and deeply. There are many places where the relationship can be personalized. These include:

- Content and language—Onboarding, messages, marketing, websites, and apps should all be personalized. Many institutions that set out to personalize underestimate how much content they will need to have on hand to truly tailor what the consumer sees to their needs and preferences. “Even content can’t be one-size-fits-all,” Clarke insists.

- Human interactions—Empowering front-line employees, real-time insights, “whisper agents,” and “agent matching.” Whisper agents are AI-based bots that prompt call-center employees what to bring up, based on past interaction with consumers. Agent matching re-pairs consumers and call center agents where there has been a good experience in the past. “Why not use that chemistry?” is the thinking.

- Offers—Offers are not verboten. But they need to be tailored as to type of deal, pricing and the selection of product features.

Clarke suggests that learning to personalize isn’t so much rocket science as common sense. She points to Japan-based Rakuten — the “Amazon of Japan” — as an example.

Rakuten, which offers banking services, asks many questions of applicants when onboarding them. The answers received dictate much of what those consumers will see from Rakuten going forward.

Read More:

- 94% of Banking Firms Can’t Deliver on ‘Personalization Promise’

- The Psychology of Personalization In Banking

Financial Firms Worth Imitating in Your Personalization Quest

Clarke points to several financial players that have committed to personalization.

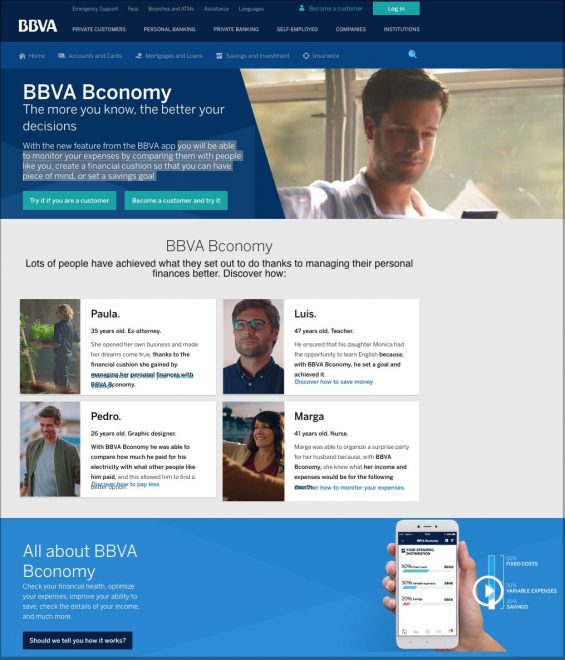

1. BBVA’s “Bconomy.” The big Spanish bank’s app is a financial wellness and budgeting tool that promises that “you will be able to monitor your expenses by comparing them with people like you, create a financial cushion so that you can have piece of mind, or set a savings goal.”

Clarke says the software asks questions to determine what is important to the consumer and the types of advice offered hinge on that. Without those facts, institutions can’t possibly personalize services in a meaningful way. She notes that 500,000 consumers signed up the first day the bank offered it. (This service is not presently available to U.S. consumers.)

While Bconomy is open only to customers, Clarke notes that BBVA’s “baby planner,” which helps consumers figure out how to afford children, is available to non-customers.

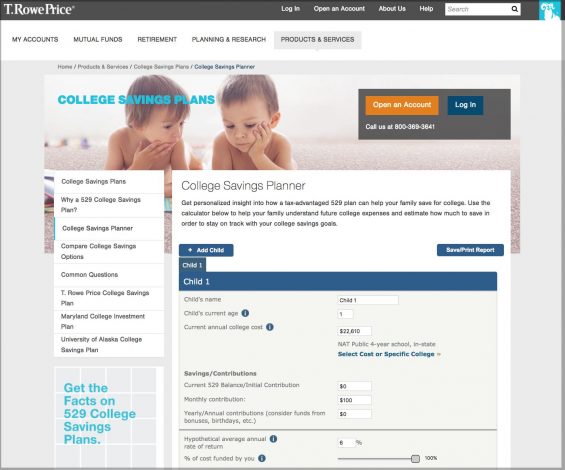

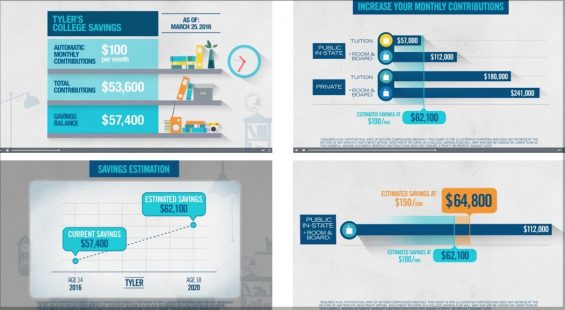

2. T. Rowe Price’s College Savings Planner collects a great deal of personal information from interested consumers and uses it to not only drive recommendations, but produce a customized video including inclusion of the child’s name. The plan below involved a child named Tyler.

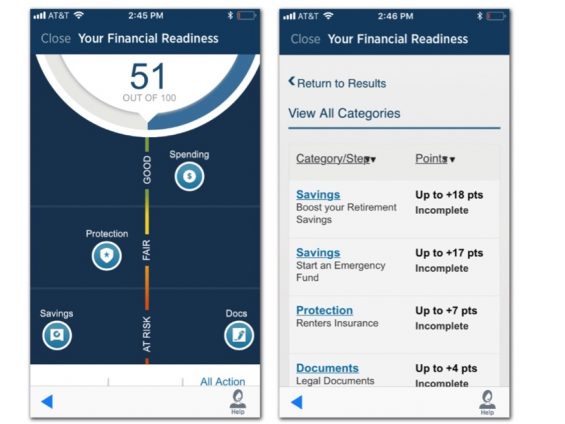

3. USAA’s Financial Readiness Score program pulls in relevant data from account holders’ existing relationships with the savings bank, and prompts the user to input data from additional sources outside of their USAA relationships.

The software produces the original score and provides recommendations for improving that number.

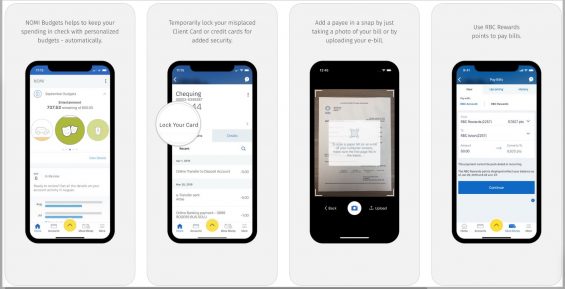

4. Royal Bank of Canada’s NOMI (“Know Me”) is a personalized app that assists in budgeting, monitoring spending, and assisting savings. One feature, “Find & Save,” makes automatic transfers from checking to savings on the basis of analysis of past spending.

This AI-driven assistance is designed to help would-be savers become savers.

The app “reduces cognitive stress for the consumer,” says Clarke. She explains that many consumers wish to save, but always mean to start, “later — and later never comes.”

Looking at Personalization’s Future

Financial institutions that decide to make a real commitment to personalization face a long do list, but the good news is that the task is possible, not a vague dream.

“The technology exists now to completely personalize your public side,” says Clarke.

“I am still completely flabbergasted at how much remains one-size-fits-all,” she adds. Something banking companies must learn to do is iterate. “It’s not a big bang,” says Clarke. “You’ve got to test and learn and grow.”