The startling ease of using Amazon One — and the growth in consumer use of the palm-recognition payments technology — just begs for a handy pun or play on words. Something like:

“You’ve got to hand it to Amazon.”

As a payment device, the palm is tough to beat for convenience — you might even say it wins, hands down. You can’t absent-mindedly leave it at home like a credit card that’s infrequently used or a dongle that’s attached to a key ring. You don’t even need to pull out your phone. And since the palm is “original equipment” so to speak, it has more appeal than the idea one U.K. company was promoting a year or so ago to implant payment chips in people’s hands.

Amazon introduced its Amazon One payment service in September 2020 as “a fast, convenient, contactless way for people to use their palm to make everyday activities like paying at a store, presenting a loyalty card, entering a location like a stadium, or badging into work more effortless,” in the words of an Amazon blog at the time. (The company had filed a patent application for the technology in 2018 and it was granted in late 2020.)

Amazon announced in July 2023 that the technology had been used over 3 million times and that it would begin a major expansion of Amazon One to bring it to all 500 of its Whole Foods Market stores in the United States by the end of the year. At the time, it was in place at about 200 Whole Foods Markets, along with Amazon Fresh stores and other non-Amazon locations. (Whole Foods is an upscale organic grocery. Amazon Fresh, which is undergoing strategic reevaluation by Amazon, is intended as a mainstream, mass-market play involving physical grocery stores owned by Amazon. It originated as a delivery service.)

“This means Whole Foods Market customers who choose to use Amazon One will no longer need their wallet or even a phone to pay — they can simply hover their palm over an Amazon One device,” Amazon said in the announcement. Amazon Prime members who link their account to their palm get their in-store prime savings automatically when they check out.

Do consumers feel comfortable with this idea? What is Amazon up to? How does it work? How secure is it? And finally, what does it feel like to use it? The Financial Brand set off to find out.

The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th

Explore the big ideas, new innovations and latest trends reshaping banking at The Financial Brand Forum. Will you be there? Don't get left behind.

Read More about The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th

The unfair advantage for financial brands.

Offering aggressive financial marketing strategies custom-built for leaders looking to redefine industry norms and establish market dominance.

Consumers Aren’t Very Comfortable with Amazon One … Yet

Amazon is clearly pushing the Amazon One palm technology, but many people will need time to get used to the idea.

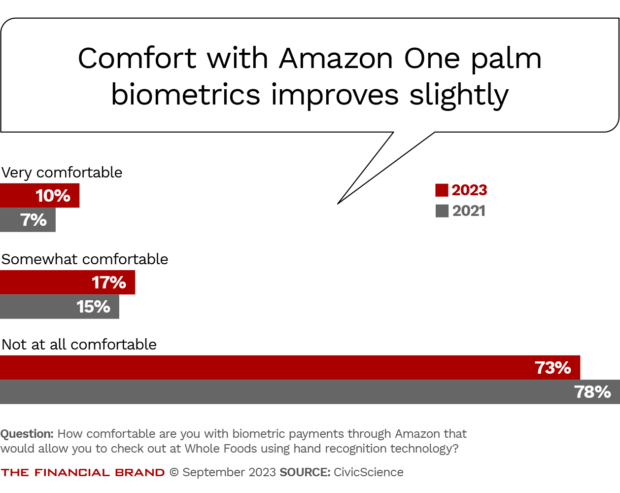

CivicScience surveyed consumers twice about their comfort level with palm recognition technology, in 2019, when Amazon had announced it was coming, and during July 2023. This year, 10% said they were “very comfortable” with the technology, an improvement from 2019, when 7% were. This year 17% said they were “somewhat comfortable” with the tech, compared with 15% in 2019. As the chart below shows, there’s only been a five-percentage-point change among those who describe themselves as “not at all comfortable.”

One bright spot for Amazon in the CivicScience research is that just over a third of consumers who already use mobile payment apps say they are at least “somewhat comfortable” with palm payments. Yet 66% are “not at all comfortable.”

This is a significant point because in some circles Amazon One technology is seen as much more than a way to pay seamlessly at Amazon locations. It’s being used at a handful of Panera restaurants and other retail locations for purchases and has been used for access at concerts. But the stakes could be much bigger.

“Amazon’s expansion of this biometric technology … is an effort to compete with Google and especially Apple in the realm of digital wallets,” says Christopher Mims, a Wall Street Journal tech columnist. (And remember that digital wallets also handle identity documents and other purposes.)

Mims goes on to suggest that it could be a long-shot play, as Amazon hasn’t succeeded thus far in becoming a major payments player in the league of the likes of Apple, PayPal and Square.

On the other hand, “this is Amazon — a company with the kind of resources and patience that allowed it to go from being a giant in ecommerce to also being the world’s leading provider of cloud computing,” Mims says.

Read more: How to Unleash the Full Potential of Digital Wallets

What’s Going on Inside the Amazon One Palm Reader

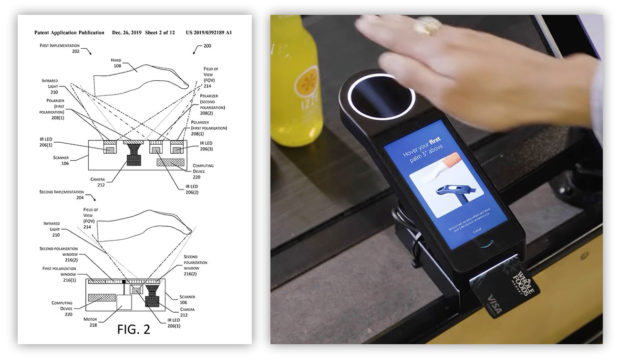

The title on Amazon’s patent for Amazon One is “non-contact biometric identification system.” The photo below from Amazon’s website shows how it looks to the consumer. The diagram, taken from the patent application, gives an idea of what’s going on inside the device. We’ll keep the description highly simplified.

When people register, they are asked to show both palms, one at a time. The hand scanner records the user’s palms in two ways, using two different light sources and two different cameras. (While this is going on, during the registration phase the card for the account the user wants to link to their palm is sitting in a built-in card reader. Additional data is input along the way with an incorporated touch screen.)

The diagram from Amazon’s patent application for Amazon One shows what’s going on behind the experience that the consumer sees. The black shapes represent the two types of cameras that Amazon One uses to build its data about the consumer’s hand.

One camera uses infrared light at one “polarization” to record characteristics of the palm that could be observed by the human eye, such as wrinkles. (Very simply put, polarization in this context concerns the direction of the light.)

A second camera uses infrared light at a different polarization to go beneath the user’s skin to photograph the pattern of the person’s veins. The frequency of the light is absorbed by the hemoglobin in the blood, which reveals the pattern. When lit this way and photographed, that vein pattern, which is unique to each human, functions similarly to a fingerprint but on a grander scale. The roots of vein pattern recognition technology go back to the early 1980s when a Kodak engineer in the U.K. had his bank cards and his identity stolen and he wanted to solve the problem. One advantage this kind of biometrics has is that it is less intrusive than having a retina scan.

These two scans are just the beginning. The system uses a neural network — a form of artificial intelligence considered to be machine learning — to analyze the images. Generative AI also played a role, specifically, training the system to recognize palm characteristics. The patent application contains many pages of detailed technical explanation of the steps involved.

“Amazon One does not use raw palm images to identify a person. Instead, it looks at both palm and underlying vein structure to create a unique numerical, vector representation — called a palm signature — for identity matching,” Gerard Medioni wrote in an Amazon blog from June 2023. He is vice president and distinguished scientist, at AWS Applications, part of the Amazon organization. He said in the blog that after millions of interactions with the system there had not been a single false positive.

Read more:

- Is CFPB’s Mobile Payments Salvo at Apple & Google Good for the Industry?

- Wearables: The Future of Watches, Rings & Bracelets in Payments

Is Amazon One Secure?

The issue of security arises because of the past history of palm biometrics. In late 2018, in an episode initially reported by the online publication Motherboard, “Hackers Make a Fake Hand to Beat Vein Authentication,” white-hat hackers created a crude fake hand from wax that was used to fool a vein sensor device. The hackers claimed to have photographed their own palms with a single-lens reflex camera with its infrared filter removed in order to capture their vein patterns and then replicate them in wax.

Coming up with a way to beat a biometric system is called “spoofing.” In an April 2021 interview with a Syracuse University publication, professor Vir Phoha, who teaches biometrics there, raised concerns about Amazon One. He noted that “there is a lot of overlap in the structure of hands of different people.” He also said techniques using silicon gloves can be used to replicate palm prints left on glass surfaces, for example. In a follow-up interview with The Financial Brand, he said this would hinge on having sufficient details about the person’s hand, as a beginning.

When asked about these challenges, Amazon responded by referencing Medioni’s blog.

“Your palm’s unique characteristics, such as creases, friction ridges and underlying vein network, are a result of independent biological processes — even identical twins with the same DNA do not have the same palm surface and vein patterns,” the AWS scientist wrote. “While your palm and vein patterns are permanent, the digital signature we use for identification is not. This allows us to delete palm signatures, and generate new ones, at any time.”

Amazon also stated in the blog that it had added something to the process that it calls “liveness detection.” The blog said that this enables Amazon One to tell the difference between a live palm and a replica.

“We even tested Amazon One with more than 1,000 silicone and 3D printed palms and Amazon One rejected those attempts,” Medioni wrote.

Would the Syracuse University professor use Amazon One himself? Phoha says he would be inclined to, because the process necessary to produce a workable fake is not a common skill.

However, Phoha suggests that a secondary form of ID verification, also biometric, be incorporated. He says this could be facial ID or even identification of the user by their gait — characteristics of how they walk. One way of capturing the latter is using the gyroscope and accelerometer that are built into smartphones and similar devices, which can be used by diet and fitness apps to track steps and miles walked. The same tools can capture gait as an identifier.

One last point from Medioni’s blog: “While most people are comfortable saving biometric data on their persona devices, the Amazon Web Services cloud protects sensitive customer data by offering several enhanced security capabilities not available on your phone.”

Getting that, Apple and Google?

Read more:

- Paze Digital Wallet Launch Delayed to Early 2024 – Here’s the New Plan

- In a Superapp Race, Apple’s Far Ahead of Twitter & Everybody Else

Taking a Test Drive in an Amazon Fresh Store

My wife is a good sport, so when I suggested that we try out Amazon One at the one company location in our area that’s set up for it, an Amazon Fresh Store, she agreed.

You can follow our progress along in the photos below, by number.

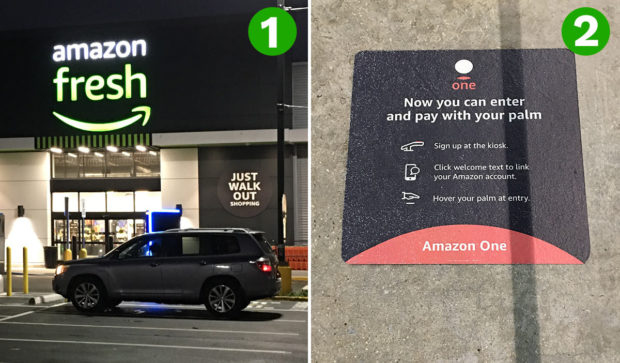

After seeing several reminders up front that we could just grab our groceries and go (1), we continued in our resolve to try out Amazon One (2).

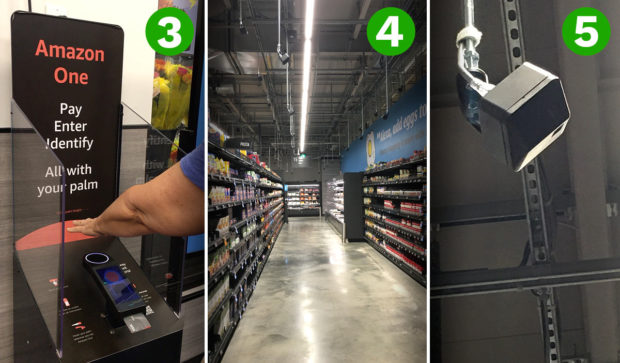

The registration terminal (3) is right inside the Amazon Fresh foyer. My wife put in one of our credit cards, had her palms scanned and entered a bit of information. Time elapsed: under 30 seconds. Not even enough time for me to browse a copy of the paper sales circular for the store that I grabbed from a pile nearby. (It seemed odd in a store that was otherwise so devoted to gadgets, but it did contain four QR codes to obtain special deals.)

At the entrance gate, my wife waved her hand over a palm reader, and I scooted in behind her, as the gate opened. Above the aisles (4) is a veritable forest of monitoring cameras to see and record what shoppers take from the shelves. This (closeup, in 5) reminds me of a maxim my mother used to enforce when cookies or rolls were placed on the dinner table, “You touch it; you take it.”

Signage here and there (6) reminds shoppers that there are deals for Prime members.

Some Amazon Fresh stores provide Dash Carts, special shopping carts that let you scan groceries as you load them in your cart using a dashboard on the cart itself. This store didn’t include that feature, as it is set up for “Just Walk Out” service.

But there are periodic places where you can consult Alexa, the Amazon voice assistant, to find particular grocery items or ask where to find the bathroom. And, as you shop, since what you are buying is being tracked as you grab it, you can bag. In our area, plastic bags are discouraged and bringing your own bag is encouraged, but for those who forget (we didn’t), there are displays here and there where you can pluck a paper bag. (7)

There’s a charge for that, and it’s incurred as you take the bag, same as would happen with an avocado or a can of tomato soup.

What happens if you pick up a can of soup, say, and discover it has an ingredient you can’t eat? Amazon says anything taken off a shelf is automatically added to their virtual cart, and anything put back on the shelf comes out of the virtual cart. Many areas of the store also use shelf sensor technology.

Once you’re done, you leave via gates that include a palm reader. My wife waved again, and we were billed in the ether somewhere, to receive our receipt later, in our Amazon account.

On the way out my wife asked a cashier why he was there.

“Now and then,” he said, “we still get cash customers.”