There’s an interesting linguistic phenomenon in the banking world. Many financial institutions seem to use “Millennial” as the perennial synonym for “young consumer.”

This is a flawed — even dangerous — definition, with serious consequences.

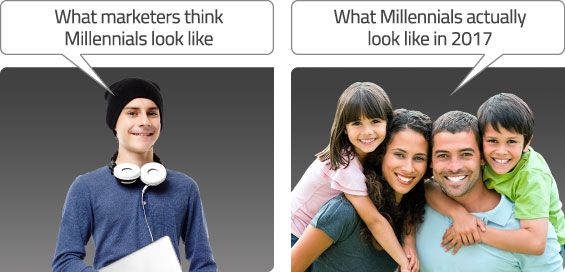

Banks and credit unions have been wrestling with how to connect with Millennials for more than a decade now. In the meantime, the audience that they once thought of as “kids” has grown up. They graduated college. They got married, and have kids of their own now.

The term “Millennial” was coined to describe a generation that would be coming of age at the turn of the millennium. In other words, kids who were becoming adults around the year 2000… 17 years ago.

Reality Check: It’s now 2017. How much does a kid graduating high school today have in common with someone who graduated back in the year 2000? Probably about as much as true Millennials share in common with Gen Xers.

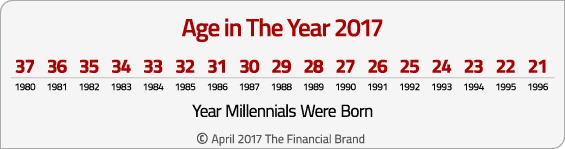

The majority of researchers and demographers define the start the Millennial generation in the early 1980s, and many end the generation in the mid-1990s. PricewaterhouseCoopers and Edelman use 1980 through 1995. Gallup uses the years 1980 though 1996. Ernst and Young uses 1981 through 1996. The Financial Brand has been using a similar age range since we published our first article on Millennials (or “Gen Y” as it was called back then) in 2008 — nearly ten years ago.

Now you have to really think about that. Demographers define the oldest Millennials as those born in the year 1980. That means they graduated high school at the age of 18 back in 1998. Today, that person would be 37 years old. There’s a big difference between a Millennial who discovered iPhones and Facebook in their teens and someone who was born in the year 2000 who never knew a world without the internet and tablets. To Millennials, iPhones and Facebook were once a novelty; but to Gen Z they are passé and taken entirely for granted — much in the same way Millennials don’t get always get Gen X jokes about brick phones, TV “clickers” and Betamax.

Reality Check: If you think “young person” when you think of Millennials, you’re way off. Nearly half are over the age of 30. Some of the older Millennials already have grandkids.

Even if you use 2000 as the outer edge to cut off the birth year for Millennials (as very few do), you still need to acknowledge that the bulk of this generation has grown up and is out of school. And yet many financial marketers still talk about targeting young people (e.g., high school age consumers, or even younger) in the context of their “Millennial strategy.”

Reality Check: Millennials aren’t looking for a “Student Checking Account” anymore. Or their first credit card. Or that first auto loan. They are now mature, mid-life financial consumers, facing all the same questions about banking and money management that previous generations wrestled with before them when they were in their late 20s and early 30s.

Read More:

- It’s Time To Stop Treating Millennials as a Single Segment

- Make Way for the Millennial Borrower

- Are You Ready For The Millennial Mortgage Boom?

Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Achieve a better return on your marketing investment. Leverage behavioral data and analytics to target the right customers with the best possible offers.

Read More about Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Instant Messaging. Instant Impact.

Connect with your customers and provide lightning-fast support as effortlessly as texting friends. Two-way SMS text messaging is no longer optional.

Now roll back to the year 2004, when financial institutions first woke up to the reality of the Millennial generation. Banks and credit unions started wondering how they were going to cultivate profitable relationships with these consumers — auto and home loans, to be specific. Everyone in the financial industry wanted to lock up Millennials with checking accounts to establish that coveted “PFI” status, hoping that they could secure those relationships long enough to turn them from pure depositors into profitable borrowers.

But that was 13 years ago. Today, Millennials are looking at buying their second or third car — not their first. Plenty are looking at getting their second mortgage — not their first.

That’s why Millennials have consistently said in one research study after another that they see value in physical branches (a fact that seems to surprise many in the financial industry). Granted, they don’t see much point in conducting basic transactions in branches, but they do see value in having higher level financial conversations with people they can trust.

Millennials aren’t worried about the basics of banking — e.g., “What is my credit score?” They have moved on to more advanced financial matters, like wondering how they might support their parents and provide for their medical needs. Or for instance, a Millennial today could be buying a new house, wondering if they should consolidate their student loan and credit card debt into their new mortgage. Or saving for their own kids’ college education. These are the kinds of financial questions that can’t easily be addressed through live web chats, mobile apps or 140-character tweets.

And yet many financial marketers still think of “Millennials” as “kids” in high school or college. This leads to “Millennial marketing strategies” built around financial education programs. And some financial institutions still think the best way to win with “Millennials” is to market to their parents — that these “kids” will bank wherever their parents tell them to. If this sounds like your institution, stop right there. Remove the word “Millennial” everywhere it appears in your strategy and replace it with “Gen Z.”

For that matter, you might consider tossing out generational labels altogether. Lumping all consumers from a 20-year span together in a single segment is the kind of crude demography that might have made sense back in the 1990s, but not in the Digital Age. Generational labels like “Gen X” and “Boomers” are merely terms of convenience — broad descriptors that socio-anthropologists and the media like to use — not strategic segments used by sophisticated modern marketers.

These days, with all the data and information at financial marketers’ fingertips, banks and credit unions can must define their segments with greater precision. Simply dividing your target audience into three clusters based on little more than age — Millennials, Gen X and Boomers — is only a slight improvement over saying you target everyone with a wallet and a pulse. Continuing to build marketing campaigns around these generational labels is akin to using only ZIP codes and household incomes as the basis of a segmentation strategy. Sure, basic demographic information like this was commonly used… 20 years ago. But we’ve come a long way since then. Data- and behavioral sciences now afford much more robust approaches to modeling audiences — from “look-alike” targeting to predictive analytics.

At the end of the day, every bank and credit union needs to be thinking about how they want to handle the youngest members of society, and there are two fundamental schools of thought here. One says that you should try to win relationships at an early age and hope/pray inertia sets in. In this first approach, the financial institution is willing to provide kids (up to age 18) with low-balance, high-cost checking accounts for many years, assuming that these consumers will remain loyal and eventually turn into borrowers when they come of age.

The other school of thought says that a banking provider should dismiss and ignore younger consumers until they actually have profit potential (after age 18, or even later). They are willing to let other banks and credit unions provide costly checking services for kids who will someday move away from home, and when they do, they will be looking for a new banking provider.

The first approach looks to “fill the funnel” with new relationships earlier in a person’s life, while the second approach waits until later. Both arguably have their own risks and advantages. It’s simply about defining the earliest lifestage that a financial institution is willing to target. Will you- or will you not offer checking accounts for kids? If so, is it because you are targeting the parents and not the kids themselves? Do you need to have an aggressive and robust financial education program, or not? Should you be forging connections and making inroads at schools to cultivate relationships with student before they graduate?

Either way, you need to define your institution’s approach to younger consumers. And it’s probably best that you don’t use generational labels “Millennial” or “Gen Z” when you do. Because before you know it, Gen Z will be all grown up too.