A young woman with a retail job needs more income — let’s call her “Katrina” — so she seeks out additional work online for her days off. After exploring a couple of possibilities, she applies to be a shopper for Instacart.

The company offers busy consumers the aid of freelance shoppers like Katrina to tackle their lists at supermarkets, warehouse stores, and even chain pharmacies, all from the convenience of their computers or via an app.

After qualifying online — even demonstrating via smartphone photo that she owns appropriate insulated carriers for perishables and frozens — Katrina is onboarded as a full-service shopper. This means that she not only handles each Instacart consumer’s shopping, but also delivers it to their door, using GPS. The transaction finishes with a photo to verify that it was she who delivered the goods, and the Instacart app records not only her fee for the trip but also any tip given.

Welcome to a growing sector of the workforce both in the U.S. and abroad, the “gig economy.” Part-time work that’s not on a payroll has existed for ages, and temp jobs and other short-term employment opportunities have been around for decades.

What sets this apart today is the role of online platforms and their associated apps that connect those with labor to offer with those who need the labor, with a flexibility and spontaneity undreamed of before.

People who work in the gig economy need banking services, and some are more readily available than others. In a whitepaper Katabat notes that the sporadic nature of some gig economy income can make it harder for consumers who depend heavily on this work to obtain credit. Gig workers’ income can swing up and down, and they often lack the safety nets that traditional employment provides. There are no sick days for most gig workers — if they don’t work, they don’t earn. Collecting fees on a timely basis can be an issue for many, though the growing number of gig platforms are in part built on assurance of getting what’s due, and quickly.

Instant Messaging. Instant Impact.

Connect with your customers and provide lightning-fast support as effortlessly as texting friends. Two-way SMS text messaging is no longer optional.

Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

Build a modern credit card strategy that balances profitability and risk, adopts the latest technology and delivers the customization that cardholders demand.

Read More about Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

Bringing Financial Services to Gig Workers

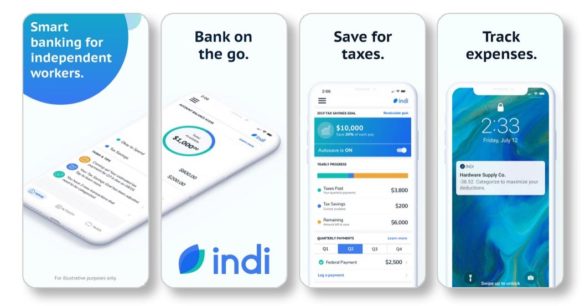

Some gig platform employers have introduced financial services for their workers, and some financial institutions have as well. For example, in 2019 PNC introduced Indi, a banking app specifically designed for gig workers. Indi was the first consumer product released by Numo, PNC’s innovation lab.

The Indi app addresses multiple pain points for running very small businesses, which is what gig work truly is. One pain point is assistance in savings towards income taxes, including reminders of quarterly payments. Two others are photo capture of receipts and automatic categorization of income and expenses, including yearend expense reports. All this with no fee for the app and no minimum balance requirement.

Other apps are also out there, such as Joust, which uses NBKC Bank accounts in order to provide insured deposits. The Joust service also includes PayArmour, an option that guarantees payment of invoices in exchange for one of two fee options. (“Joust” relates to “freelancing” and harks back to medieval times when a mercenary knight was a “free lance” who could fight, or joust, for the best offer.)

There is increasing recognition that the financial needs of this growing sector of the economy need addressing. Katabat points out in its whitepaper that the growing use of alternative credit scores is one response, as is the attraction of nontraditional lenders.

To a degree, among traditional lenders, lending to gig workers takes more work, and some out-of-the-box thinking. In a blog entry Freddie Mac explains the challenge:

“To underwrite self-employed borrowers, lenders must dissect a customer’s tax returns — versus a W2 — to validate his or her income. Complicating matters is the fact that the self-employed are incentivized to reduce their taxable income through deductions and write-offs. Loan officers and processors often must then manually reconcile dozens of pages of tax documents — including 1099s, Schedule Cs and other forms — to arrive at a reliable income total. The income-validation process can take days to unfold.”

Adding more technology to the process can help, Freddie Mac suggests.

At a time when traditional financial institutions face increasing competition on every side, adapting to this aspect of the economy may no longer be optional. Groups like The Freelancers Union, a nonprofit that curates multiple types of insurance, may fill the vacuum.

Let’s explore the size and nature of this growing market.

U.S. Gig Market Already at Hundreds of Billions

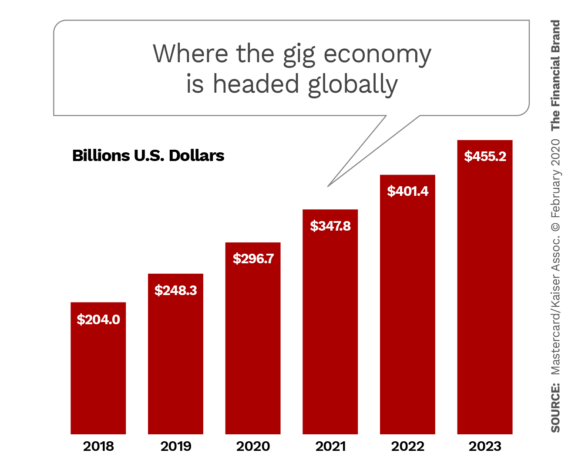

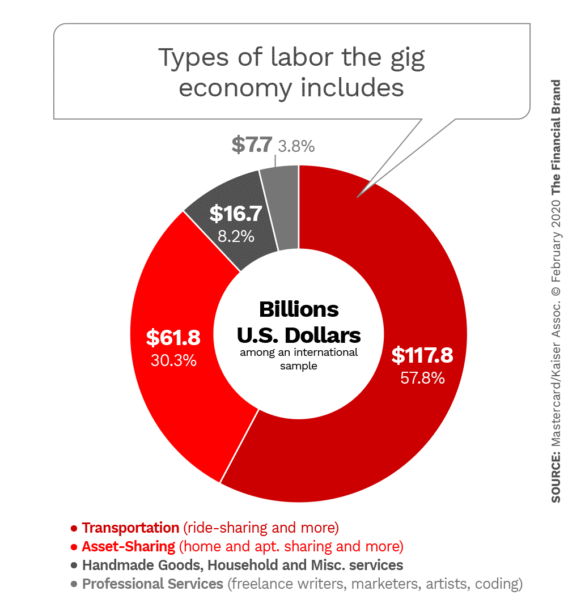

The gig economy is growing worldwide, according to research by Mastercard and Kaiser Associates, and could reach $455 billion by the end of 2023. This research indicates that in 2019 the U.S. represented 44% of the world’s gig work delivered via digital platforms. (The gig economy has multiple definitions and measurements. This study, and this article, generally concern the platform and app-based services. The figures in the pie chart and bar chart below include both gig workers’ earnings and the commission that the platforms take.)

The two big ridesharing companies Lyft and Uber account for about three out of five gig jobs internationally, but other forms of gig work continue to proliferate. Amazon offers multiple opportunities, including being an online shopper at its Whole Foods stores and a freelance delivery person via its Amazon Flex platform. TaskRabbit connects handy people with people who need things done — a common “tasker” job is assembling IKEA furniture.

And then there are sites that don’t even represent labor in the usual sense, but instead “asset-sharing.” This can include places to stay via Airbnb, parking spaces via Spot Hero, and rental of one’s own car via Turo. Even clothing has been shared via gig rental apps.

On the other side of the equation — demand for such services — segments of society, notably Millennials, like the instant nature of obtaining services from gig platforms. Businesses also have been tapping gig platforms as a means of outsourcing work. Research in the U.S. by Lightspeed/Mintel indicates that ride hailing, food delivery and lodging services have been the top three gig app services from the consumer side.

The MasterCard/Kaiser research suggests that several trends have converged to drive the growth of the gig economy via platforms. Among them: the rising costs of living, especially affecting the middle class; a societal shift towards flexible work-life arrangements; growth in potential gig workers and gig opportunities through increasing access to the web and apps via smartphones; and the evolution of attitudes about ownership of cars and more.

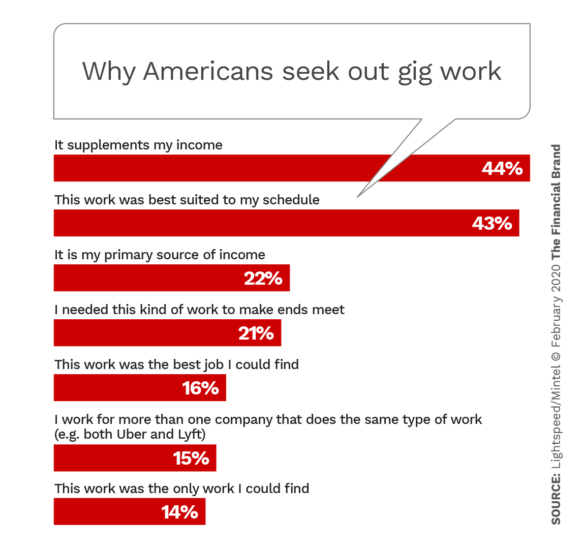

In research by Lightspeed/Mintel in the U.S. a bit over two out of five consumers doing gig work indicate that it is not their only source of income, but a supplement to their regular job, i.e., a “side hustle” or other description. But for one out of five gig workers, these jobs are their main source of earnings.

“The fact that one fifth of gig workers are already relying on alternative employment as their primary source of income, while many gig economy brands were not even operational as recently as a decade ago, underscores the incredible speed with which these brands have reshaped the employment landscape,” Mintel states.

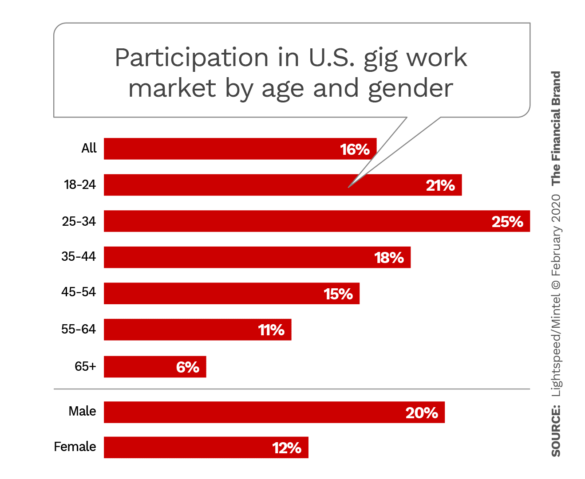

Currently, the sweet spot of gig work in the U.S. is among younger people, especially 25-34 year olds. But this could change. Earlier Mintel research among senior citizens indicates that many Baby Boomers intend to stay in the workforce in some way as long as they can.

“One in three Baby Boomers are still working full-time, and another 16% are either self-employed, freelancing or otherwise working on a part-time basis,” states Mintel’s report, “The Gig Economy.”

Field Trip: Next time you take an Uber or a Lyft, take some time to talk to your driver about their reasons for doing gig work. In the process you may learn more about the demographics of this world. We’ve tried that and found that while some drivers are young, a fair number are retired from other jobs — armed services, public sector jobs and others — and either needed the money to supplement pensions or wanted to get out and around.

Steps to Try to Serve the Gig Market

“Gig workers may be new to the economy,” Mintel states, “but they face the same financial difficulties as most average consumers, albeit often with less predictable income streams.” Financial institutions “need to figure out a way to provide real and meaningful guidance for this growing segment of workers.”

Ron Shevlin, Research Director of Cornerstone Advisors, suggests in a blog that traditional banking institutions need to move on this before newcomers outflank them.

“The needs of the emerging gig economy worker represent a need for a new type of financial product — or at the least, new features within the existing products,” Shevlin wrote. “But banks are watching this opportunity slip through their fingers.”

One bit of perspective comes from the Mastercard/Kaiser research, which notes that attrition rates can be high among gig workers. The report cites one study that found that attrition over the first six months of working for Uber hit 68%. Gig work is not for everyone, and workers, unbound by benefits and such, may feel free to try out other platforms that they perceive to offer a better deal. Mintel points out that job actions aren’t unknown, either. In 2019 Instacart workers struck to improve the default rate for tips, among other demands.

Katabat’s white paper counsels banking institutions to develop features in apps and other offerings that recognize the business needs of gig workers:

- Build in business invoicing and payment features.

- Integrate expense tracking and categorizing tools within banking apps.

- Set up loan specialist teams to devise approaches to gig workers’ credit needs.

- Partner with large gig platforms to set up programs to enable workers to receive their earnings ahead of schedule, when needed.

Mintel suggests in its report that there’s potential for good business here.

“If banks can successfully soften the financial strain of having unpredictable income and eliminate the feedback loop that often makes it more expensive to have a lower income, they will do so much to solve the problems that face not only gig workers, but large swaths of the general population as well.”