Is Carvana an internet-based used-car sales platform? Or is it an online lending platform? Actually, both — and that illustrates part of how auto sales and auto lending will continue to evolve going into a new decade. Your competition won’t be coming just from national lenders, captive finance companies, or the other financial institution in town. Some will be “invisible” in plain sight.

If you want to understand Carvana, think of Amazon not only getting into banking but also into the used-car business— complete with home delivery in its own fleet of trucks.

“Consumers currently view the car purchasing process as a necessary evil they must be subjected to in order to get a vehicle,” writes Hannah Keshishian, Automotive Analyst at Mintel, in a report. “They tolerate the current process because they feel they have no other options in terms of where to purchase from; however, as younger generations grow into their purchasing power, they might look to startups and other disrupters that will give them the experience they seek.”

And this sounds a lot like Carvana. The company — which launched as an independent concern in 2012 and which went public in 2017 — is something both local car dealers and lenders should be watching while considering the future of auto lending.

How Carvana Plays Both Seller and Lender

While a number of internet platforms exist in the highly fragmented car sales space, Carvana has strong appeal to Millennials and others who love the idea of marrying car sales and ecommerce.

“It appeals to the so-called Amazon mentality of instant gratification, doing things from the comfort of your couch while streaming Netflix in the background,” says Zachary Brown, Research Analyst at Comperemedia, a Mintel company. “People are more open to making some of the more complicated financial decisions in their lives this way.”

Consumers can shop at Carvana’s site, viewing their choice of an inventory of roughly 20,000 cars at any one time. Each vehicle has been screened and can be viewed in high resolution from multiple angles, inside and out, so the consumer can see what they’d be getting, right from their kitchen or couch. They can order the car online and then either have it delivered to their front door, ready to drive, or they can enjoy the experience of having it “dispensed” from one of Carvana’s giant vending machines. Consumers literally put a giant coin in a slot to activate the process of the dispenser positioning the car for delivery.

They have seven days to try out their car. If they decide after this prolonged test drive that they don’t want it, Carvana will pick it up, much like an ecommerce company picking up shoes that don’t fit.

Here’s the Wakeup Call. But what consumers can also do is arrange financing for their vehicle during the same online session, only needing to answer ten questions. Consumers can bring their own financing to the virtual table, but if they go with Carvana they are dealing with a seller that also does its own underwriting. Carvana is not a bank and does not portfolio the loans. They are sold to investors. As the company evolved it moved into securitization, selling its third auto loan securitization in the third quarter 2019. That was the third offering in the year.

Are You Ready for a Digital Transformation?

Unlock the potential of your financial institution's digital future with Arriba Advisors. Chart a course for growth, value and superior customer experiences.

The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Learn how to enhance your brand’s local visibility, generate more leads, and attract more customers, all while adhering to industry regulations and compliance.

Read More about The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Company officials believe they can now serve nearly 70% of the U.S. population and are working towards even higher coverage. Carvana not only sells cars but recently began buying them remotely as well.

In the Automotive News ranking of used car sales top 100 for 2018, announced in early 2019, Carvana ranked eighth, selling 94,108 vehicles. What makes that especially notable is that the company didn’t even appear in the previous ranking, when it sold 44,252 vehicles in 2017.

The quest to remove pain points in the car buying process goes beyond Carvana. Other similar platforms also offer credit. Vroom, a brand that shows up frequently in YouTube pre-roll ads and emphasizes buying via mobile device, partners with banks and other major lenders, among them JP Morgan Chase, Capital One, Ally and TD Bank. In a twist, in September 2019 Carvana and Regions Bank launched an arrangement in which a co-branded site offers the young firm’s cars and an easy segue to the bank’s online financing.

Read More:

- Beware: Customers May Cut Banks From The Digital Journey

- What Bank and Credit Union Marketers Can Learn From Auto Dealerships

- Four Ways to Beat Digital-Only Lenders at Their Own Game

Traditional Lenders Have Decisions to Make

Banks and credit unions have long worked as indirect lenders with car dealerships, buying dealer paper. AutoNation, the country’s largest auto retailer, which handles multiple brands, offers financing through third-party lenders. But the advent of a seller that also makes its own loans, albeit for sale, is a development that financial institutions have to watch closely. Consider that Quicken Loans, exclusively an online lender, became the nation’s largest mortgage lender before many local banks and credit unions realized it was a competitive threat.

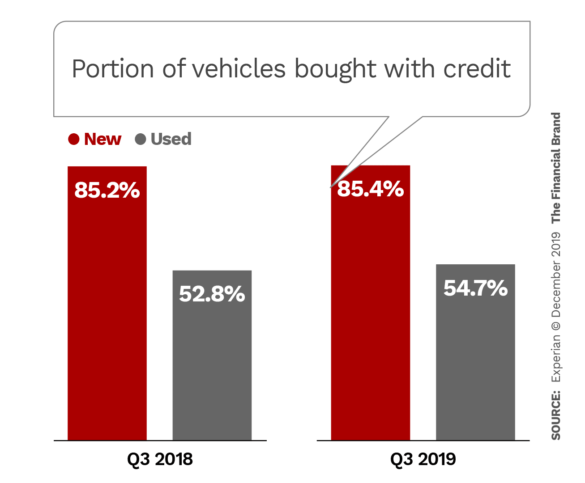

According to a late 2018 Raddon report, 65% of consumers purchase their cars with indirect credit from banks, credit unions or other lenders. The same report suggested strongly that financial institutions put more emphasis on direct auto lending, in order to maximize cross-selling opportunities.

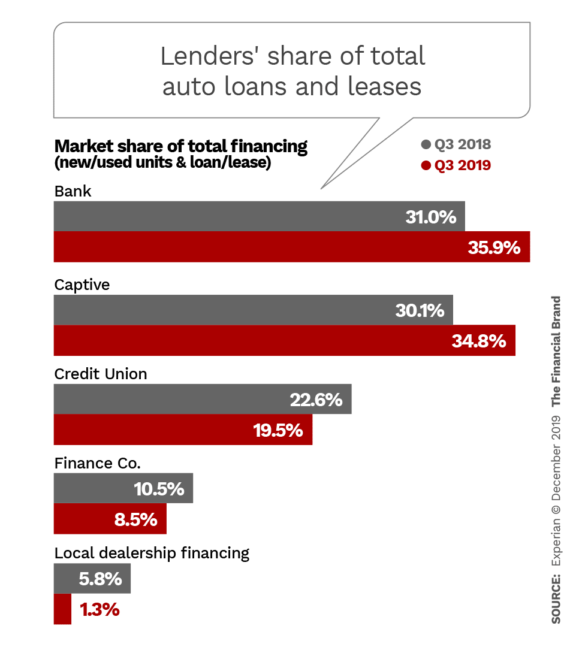

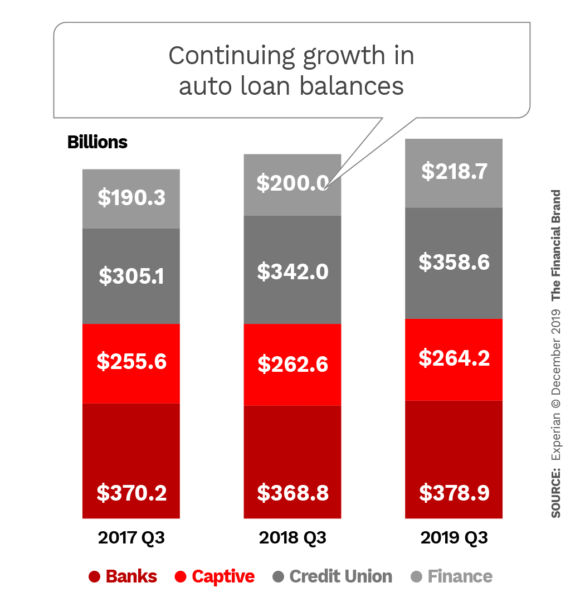

Auto loan balances are at record highs, notes Zachary Brown, Research Analyst at Comperemedia, a Mintel company. At the end of the third quarter of 2019 they stood at $1.22 trillion, according to Experian. In spite of this saturation, Brown notes, his research in 2019 indicates continuing emphasis by lenders on auto loan originations, with a de-emphasis on marketing auto loan refinancings.

Brown explains that the pullback on refinancings comes from lender concern about rising delinquency rates on outstanding auto loans. In December 2019 TransUnion projected that the portion of auto loans 60 or more days past due — considered serious delinquency — would tick up slightly to 1.47% once the quarter ended. But while this is up a bit from the fourth quarter of 2016 (1.44%), TransUnion says that serious delinquency levels continue to be historically low.

The lenders’ reticence may be leading to a missed opportunity. While there is a preference for originations, TransUnion expects to see increasing issues over auto affordability going into 2020. As new vehicle prices continue to rise, sales will decline, the firm notes. While overall auto loan balances will continue to grow, the rate will slow in 2020 as the price issue continues to bear. More competition for fewer loans.

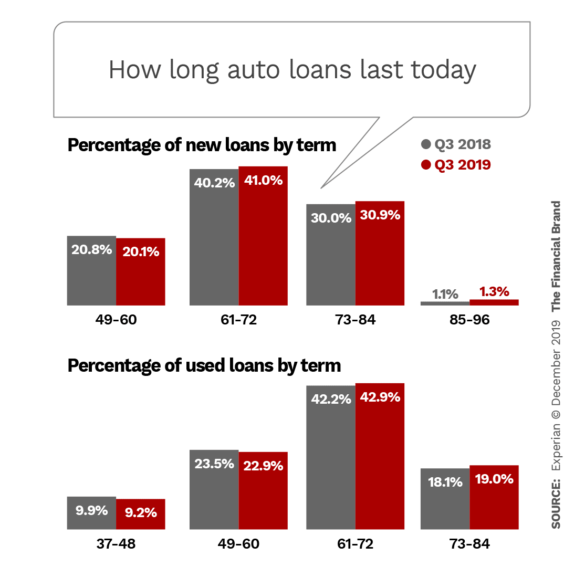

Which ends first, the car or the loan? One way that some consumers will attempt to deal with the price issue is extending their terms, a practice that has been going on for years. This stretching is beginning to go to unusual lengths, with even eight-year new car loans not unheard of. It’s a matter of dealing with rising auto prices by managing the monthly payment — a longstanding tool used by auto dealers, after all. (Experian reports that the average monthly payment for a new vehicle was $550 in the third quarter of 2019, while the average monthly payment for a used vehicle reached $393.)

However, Matt Komos, Vice President of Research and Consulting for TransUnion’s financial services business unit, indicates that the company has seen this trend slow down somewhat as some lenders resist going out so far. TransUnion believes most of the growth in new loans will be among prime and above consumers as lenders exercise caution.

Comperemedia’s Brown thinks refinancing offers will have a strong chance of succeeding. He understands lenders’ hesitation, but suggests that a strong targeting strategy to sift out the best risks among existing borrowers would help.

Brown suggests that a key market would be people who graduated from college in the last few years. He reasons that many will have borrowed for their first car, once they found jobs, and are paying higher rates because they started with weak credit ratings. Having had a few years to get their financial act together, they may be in better shape and could qualify for lower rates now.

“This is a population that lenders are loving to target anyway,” says Brown. “Young people most commonly receive auto loan offers right now.” His point is instead of trying to sell them on borrowing on a new vehicle, they could refi their existing one.

While the opportunity is there, Brown suspects it will take one or two large players shifting emphasis toward refis before most traditional lenders will make the move.

That said, rivals may step in where traditional lenders don’t. TransUnion’s Komos says some fintech lenders are beginning to offer auto refinancing, some of them offering the ability to do it through your smart phone.

Among the brands that come up as pay-per-click advertisers in a Google search for car refinancing are Lending Tree, a marketplace lender, but also Clearlane. The latter is actually part of Ally Financial, a direct bank that often behaves more like a disruptor. Clearlane taps a multilender network through its marketplace. Interesting given that Ally’s roots are in auto lending, going back to when it was General Motors Acceptance Corp.

Read More: 5 Ways Banks and Credit Unions Misread Consumers Today

Stop Ignoring 55+ Year-Old Car Loan Prospects

One more opportunity that Brown suggests: Don’t let auto loan marketing dwell solely on the young.

In his report Brown notes that over half of 18-34 year-old consumers with annual incomes of $75,000 or more plan to buy a vehicle in 2020. “Current direct mail distributions reflect this area of opportunity,” Brown writes, “with young consumers making more than $50,000 receiving auto loan offers at the highest rate.”

But his research, using the firm’s consumer panels, finds that older, wealthier consumers — 55+ years old making $75,000 or more, who represent good credit risks, aren’t being tapped.

“Nearly a quarter of these people expressed intent to purchase a vehicle in the next 12 months,” in Mintel research, the report states, “but they are the least likely to receive auto loan offers.”