Frontline staff at branches across the country are getting a lot more ad hoc pricing requests than in the past. Decisionmakers, in turn, are spending more of their day approving exceptions for depositors bargaining for a better deal.

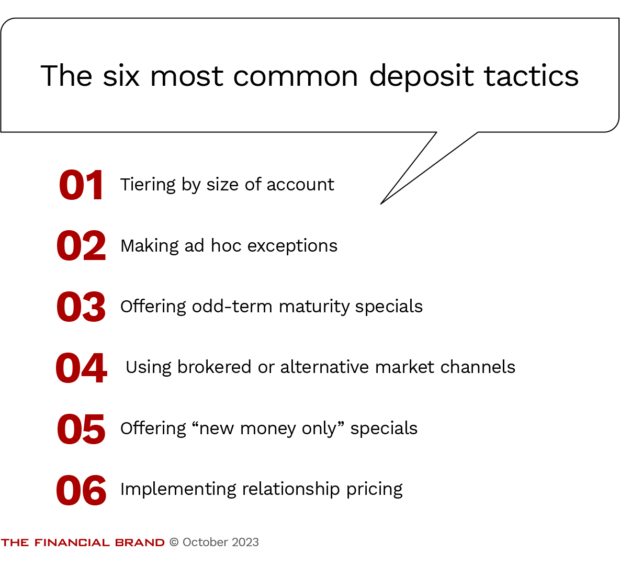

Seeking respite, financial institutions tend to consider a host of “creative” strategies to retain or attract deposits. But they should wade in carefully.

These tactics are not silver bullets. Many, including implementing relationship pricing, providing depositors a rate based on the size of an account, or offering odd-term maturity specials, can be counterproductive, depending on the situation. Others, such as ad hoc pricing, are problematic.

And two tactics — new-money-only rate specials and brokered deposits — can be outright destructive to future profitability.

No deposit tactic is “bad” or “good” in and of itself. So when and how are these tactics helpful? And how are they not?

Unlocking Digital Acquisition: A Bank’s Journey to Become Digital-First

This webinar will offer a comprehensive roadmap for digital marketing success, from building foundational capabilities and structures and forging strategic partnerships, to assembling the right team.

Read More about Unlocking Digital Acquisition: A Bank’s Journey to Become Digital-First

Are You Ready for a Digital Transformation?

Unlock the potential of your financial institution's digital future with Arriba Advisors. Chart a course for growth, value and superior customer experiences.

A Measure of Deposit Differentiation

There are four questions that executives at banks and credit unions can use to assess when and how deposit tactics fail.

1. Will it be perceived as fair and consistent by depositors and staff alike?

Consider new-money-only deposit campaigns as an example here. Do they pass this test?

Usually not with current depositors. The enthusiasm often found in asset-liability committees for these offers is certainly offset by the disappointment and frustration among existing depositors.

Frontline employees also get frustrated because they’re the ones who have to mollify loyal depositors who’ve heard about a special they cannot get.

2. Is the pricing strategy easy to understand and execute for the frontline staff?

Before answering “yes,” look deeper at how well the staff is supported by a process. For example, consider what happens when institutions acquiesce to most depositors, also known as exception or ad hoc pricing. The approach leaves the frontline staff vulnerable to rate shoppers, with many of them demanding a manager intervene if they don’t get a satisfactory answer.

3. Is a tactic valuable to depositors and the institution?

New-money-only rate specials, while they fail as a fair and consistent tactic, pass this test on the depositor side with flying colors, at least for the new depositors. Rate shoppers get what they came for: a-top-of-the-market rate. The institution gets funding while avoiding repricing current depositors. The catch is that rate shoppers have no loyalty and will likely leave for the next best rate. So, is it truly valuable to the institution in the long term?

Think Twice:

New-money-only rate specials can attract new customers. But, if their loyalty is fleeting, is this really the best tactic for achieving the institution's goals?

4. Is the approach effective at attracting and retaining the desired deposit volumes at healthy margins?

Profit is ultimately a function of spread and volume. Executives at banks and credit unions often focus solely on cost of funds, but they must never forget they also need funding volumes as well. Providing a rate based on the size of an account is an example of giving up healthy margins automatically.

The balance moves depositors into a higher interest rate, even those depositors who might have been content with the rate they already had.

An Assessment of the Each Deposit Tactic

How do common deposit tactics perform when measured by these four questions?

Tiering by size of account

It’s hard to criticize institutions that pay depositors more based on their balance. It’s fair and consistent to provide better pricing to larger relationships. Banks and credit unions have done this for decades, and core systems all anticipate and facilitate tiering automatically, making it easy for staff to manage.

Executives can avoid cannibalizing deposit volumes at healthy margins by assessing what each tier should pay depositors given the institution’s funding needs.

This tactic fails the fairness test when the institution does not provide appropriate proportionality. An example of inappropriate proportionality is paying 0.30% for balances under $100,000 while paying 4.30% for balances over $100,000.

Ad hoc or exception pricing

Haggling makes everyone uncomfortable, and the result isn’t consistent for the depositors, staff or institution. While negotiation is commonly required in engaging depositors, the ad hoc experience trains them to see staff as impertinent obstacles rather than advisors there to help them.

In the long term, the result of staff feeling their way through each interaction is slow service and executives’ ability to manage the desired deposit volumes at healthy margins is severely diminished.

Odd-term maturity specials

Markets are used to institutions offering deposit specials based on specific funding needs. Offers like a 13-month CD at 4.70% can make a lot of sense for the balance sheet; they feel fair and provide value to depositors, and the frontline staff can understand and execute them.

But, when they are part of a permanent account lineup, depositors become conditioned to promotions, and the staff becomes habituated to offering them.

Similar to cable TV and cell phone plans, however, depositors learn that the best price is only achieved by shopping. It’s not as haphazard, but odd-term specials can become a kind of planned ad hoc approach — with the result being that the institution still does not have a comprehensive deposit strategy.

Brokered or alternative market channels

Purchases of brokered deposits by institutions are generally opaque to depositors, and many institutions use alternative brands to avoid the negative consequences of not offering preferred pricing to those in their traditional markets.

The frontline staff isn’t involved in brokered CDs. And alternative market channels allow an institution to offer things like callable CDs with reduced negative impact. Calling the CD does not risk relationship damage since these are generally not relationship accounts.

Brokered deposits, however, are highly dependent on wholesale funding pricing levels, a risk to garnering deposit volumes at healthy margins. They also do not produce a long-term relationship with the end depositor.

See also: What To Know About the Alarm Over Brokered Deposits

New-money-only specials

Can you imagine sitting in front of an elderly woman as a personal banker — a longtime customer who you’ve helped at the branch numerous times — as she expresses her frustration that the bank values new money more than her money?

There’s not enough charm, hustle, or apologies, to clear the negativity from the experience for staff or for the depositor. And it’s all done to gain new money from rate shoppers who are only there for a great deal. These tactics are “a poison pill,” pure and simple.

Relationship Pricing

Bank and credit union executives frequently express the desire to deepen relationships. The tactic of relationship pricing feels fair to depositors, and frontline staff can easily assist loyal depositors in achieving a better rate.

It can be systematically put in place using years of relationship, number of related accounts, number of related services, estimated current relationship profitability, and estimated lifetime account value.

While beneficial in small doses as it aligns with the logic of the marketplace, it is not the cornerstone of a robust deposit pricing strategy because it tends to take the institution in the opposite direction from profit maximization. Institutions may want to provide relationship pricing, but they should consider carefully before automating it.

Read more:

- Unique Youth Savings Account Aims to Hook Gen Z & Gen Alpha

- See all of our latest coverage of checking accounts

The Deposit Squeeze Is On

With a cohesive deposit strategy, rather than swerving between one-off tactics, the frontline staff can avoid the downsides of each of them. The result can be funding volumes at outsized margins that institutions will need badly this year and next.

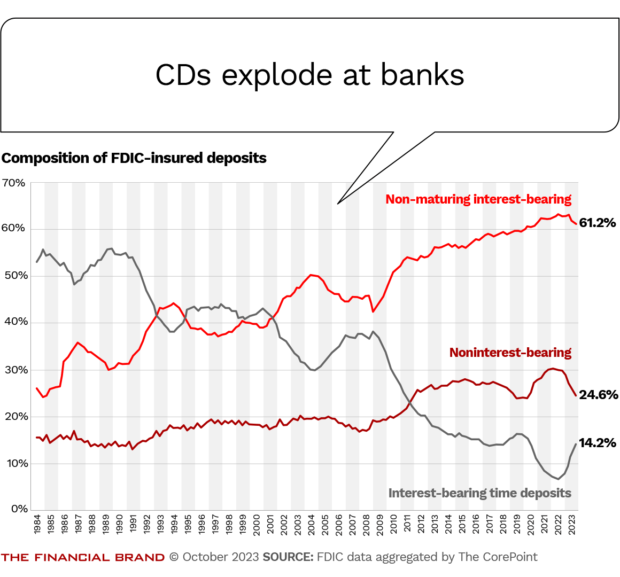

Data on banking institutions’ deposit composition shows steep declines in noninterest-bearing deposits in recent quarters. Both institutions and depositors are embracing certificates of deposit.

At banks, CDs have gained more volume in 12 months — second quarter 2023 to second quarter 2022 — than they have since the turn of the century.

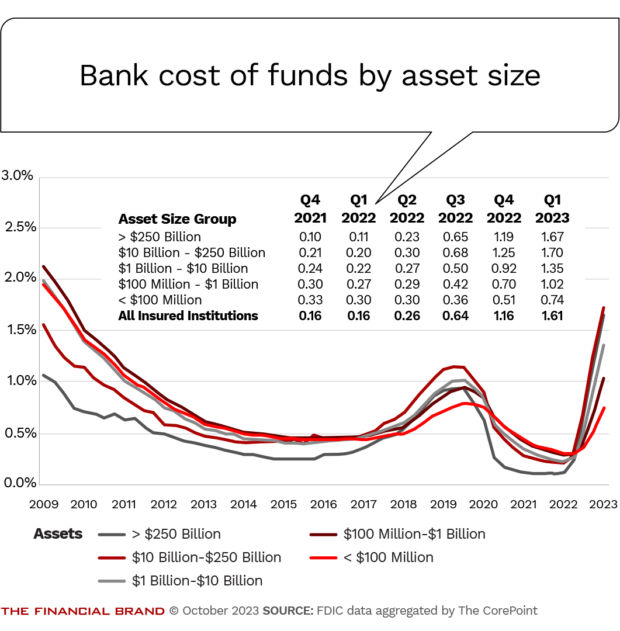

In just a year, total interest expense — a metric showing what deposits cost banks — has climbed by more than 400%, according to second-quarter data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Across the spectrum of bank sizes, cost of funds now exceeds levels not seen since 2009, especially for banks $1 billion and above.

Rates have entered a new reality. While they may decline some, they are unlikely to go back down to 2022 levels. The Fed funds target is 5.25% to 5.50%, as of this writing. CME FedWatch, which forecasts the probability of rate increases or decreases by the Federal Reserve, currently indicates overnight rates are unlikely to fall below 4% until December 2024.

Read more:

- The Art of Pricing: Growing Loans and Deposits by Optimizing Rates

- How Deposit Campaigns Can Grab More Dollars with IP Targeting

Which Deposit Strategy Will Keep Customers and Staff Happy?

Executives at banks and credit unions can no longer expect depositors to sleep as they have during the past 15 years. A growing number of people are becoming more active about managing where they deposit their money because it is simply in their own best interests to do so.

And now, after years of pandemic-fueled digital banking adoption, account holders have the technology at their fingertips not only to change institutions but to do so quickly.

Provide a fair and consistent offering in depositors’ eyes and equip staff to negotiate effectively. Then your institution will have its best chance of attracting the funding it needs at the best margin possible.

About the author:

Neil Stanley is the founder and chief executive officer of The CorePoint.