Credit unions will face a squeeze in 2024 that will pull down return on average assets and challenge managements through most of the year, according to the inaugural edition of the Kroll Bond Rating Agency’s “U.S. Credit Union Compendium.”

The agency says credit unions are seeing pressures parallel to those that beset the banking industry, but with important differences due to each industry’s funding practices, typical loan concentrations, and approaches to liquidity.

One positive for credit unions versus banks is that they typically maintain much thinner investment portfolios because they tend to devote a greater portion of their assets to lending to members, according to Brian Ropp, managing director, financial institutions, at Kroll.

As a result, Ropp pointed out in an interview with The Financial Brand most credit unions don’t have the underwater investment portfolios that shadow many banks. Likewise, he adds, on the whole the industry has much less involvement in commercial real estate lending, a threat overhanging many banks.

However, credit unions do generally have much more exposure to consumer credit travails. Compared to commercial and industrial loans, which he says have been surprisingly resilient for banks, Kroll considers this a significant exposure.

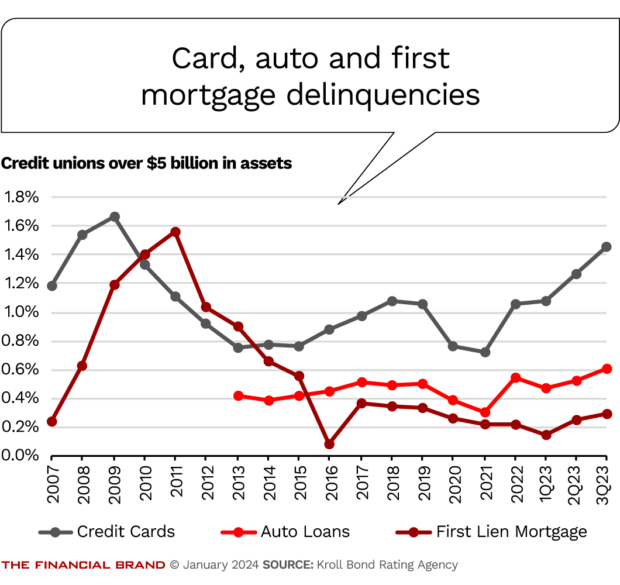

Kroll expects that exposure to continue to be worrisome throughout 2024, thanks to persistently higher interest rates, falling liquidity, and deteriorating consumer credit quality — especially in auto loans, a credit union staple.

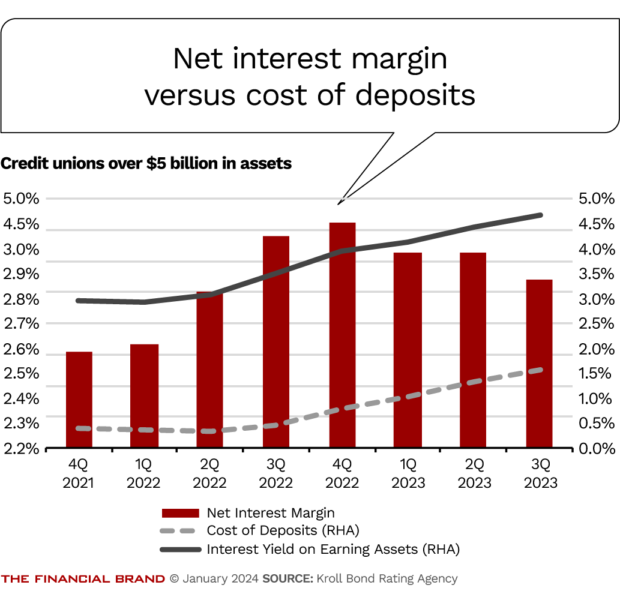

“The credit union industry’s ROAA has dropped from almost 1% in the third quarter of 2022 to 0.59% in the third quarter of 2023. So, the industry has seen a 40-basis point drop in earnings power, which would typically have been its first line of defense.”

— Brian Ropp, Kroll Bond Rating Agency

Faltering asset quality means credit unions will have to provision more to loan loss reserves at a time when both net interest margins and earnings power are declining. Under current conditions Kroll expects net interest margins to continue to tighten.

Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Achieve a better return on your marketing investment. Leverage behavioral data and analytics to target the right customers with the best possible offers.

Read More about Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Learn how to enhance your brand’s local visibility, generate more leads, and attract more customers, all while adhering to industry regulations and compliance.

Read More about The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Looking at Credit Union Loan Quality

Like banks, credit unions enjoyed an influx of stimulus funds from government programs that enabled them to expand lending. But as those funds have gradually gone away, the industry’s loan-to-deposit ratio has gone from 74% in the fourth quarter of 2021 to 91% in the third quarter of 2023. The latter figure is a blip over the median level of 90% seen in pre-pandemic 2019, according to Kroll’s report.

Credit card lending by credit unions has also seen weakening credit quality, but much of that occurs among larger credit unions, those with over $5 billion in assets. For the latter group, Kroll reports that card credit deterioration has been a bigger issue than auto trouble.

“Credit card delinquencies are at their highest point in a decade,” according to Kroll’s study.

Auto lending trouble arises from several causes. One is that consumers who were flush with funds have wound down much of that liquidity and they are starting to experience some stress repaying loans.

“We’ve talked to credit unions that are starting to see defaults on auto loans,” Ropp says. Thus far unemployment has not been a significant factor. However, “higher interest rates have definitely impacted marginal borrowers,” says Ropp, contributing to auto delinquencies.

From our archives: NCUA Chief’s Top Worries: Deposit Pressure, Loan Pricing and Fintech Partnerships

Many of the auto loans beginning to experience trouble were made during the height of the pandemic. Sticker prices ran higher in that period — remember, there was a backlog in auto production due to lockdowns and supply chain issues. Ropp points out that higher prices continued from 2020 through to part of 2022.

Auto loans made during that period are underwater, in terms of the value of the auto collateral now versus when the loans were closed. Prices have stabilized at lower levels so that when a credit union gets a car back, the outstanding loan balance is often higher than the value of current models of identical vehicles.

“We talked to one credit union that said that they are realizing close to 40 cents on the dollar when they have to foreclose and repossess and take the car to auction. So, they are basically writing off 60 cents on the dollar among vintages made during the COVID period.”

— Brian Ropp, Kroll Bond Rating Agency

Getting past this will require two things, suggests Ropp. One is continued stability in employment, to avoiding increasing default rates. (As of the January unemployment report, indicating steady hiring and unemployment rates, this has some promise.) And a drop in interest rates in the near future would enable many auto borrowers to refinance their vehicles at lower rates, which would provide some relief. However, Ropp thinks Federal Reserve policy and market conditions won’t produce that for at least a couple of more quarters.

“It’s a little bit like the proverbial pig in the python right now,” Ropp says in relation to the combination of higher balance auto loans at higher rates. “I’m hoping that by the second half we’ll have gotten through this and see some stability on the asset quality side.”

One footnote on autos: Ropp says the issues around electric vehicles are not an issue for credit unions right now. They represent a very small percentage of their loan base.

“Even if the volume of purchases was ticking up, EVs would still be somewhat of a rounding error,” says Ropp.

Read more:

- Five of the Best: How Banks Chased Deposit and Loan Growth in 2023

- 4 Surprising Charts on What’s Buoying the U.S. Economy

- Fintechs Powered the Growth of Unsecured Personal Loans. What Risks Are Emerging for Consumers and Lenders Alike?

The Funding Side of Today’s Credit Unions — and a Leading Edge Strategy

Historically, credit unions have enjoyed a strong deposit funding base. Ropp says that in the current environment of higher rates has meant changes. Credit unions are paying up for deposits, overall, as more noninterest-bearing balances shift into interest bearing. However, they retain access to those deposits, for the most part, and supplement them, to a degree, with limited amounts of brokered deposits, the report indicates. Deposit insurance continues to be a funding advantage.

Among larger credit unions, those with more than $5 billion in assets, and among those that have grown significantly in the last couple of years, there has been increased reliance on wholesale borrowing to make up for the gap seen between assets and deposits.

Borrowings in this group of credit unions have grown four-fold, “from a minimal 2% of total funding to a still-manageable 8%,” according to the Kroll report. (Banks of similar size are up to 11%.) The two chief sources of borrowed funds for credit unions today are the Federal Home Loan Bank System and the Federal Reserve, Ropp says.

Financing is more broadly available via subordinated debt. Ropp says that the National Credit Union Administration began permitting a greater number of credit unions to begin using these securities in 2022. Buyers include other credit unions, institutional investors and some banks. (Part of the reason for Kroll’s issuing its report was ratings announcements on five credit unions that are among newer users of subordinated debt.)

Ropp says credit union users of subordinated debt still represent a limited group of institutions, but the ability to tap this resource helps because credit unions, as mutual organizations, have few sources of capital outside of retained earnings. Credit unions can’t sell common stock, as banks routinely do. Lacking holding companies, credit unions benefit directly from proceeds from subordinated debt, which count as secondary capital, he says. On the other hand, because of their tax-advantaged status, while banks can deduct the interest paid on subordinated debt, credit unions can’t.

“We expect the industry to focus on capital preservation through periods of economic weakness and to moderate balance sheet growth relative to prior periods,” says the Kroll report. The latter has enabled some institutions to throttle growth in operating expenses by trimming loan origination staff and mortgage banking operations.

More about credit unions: How and Why Navy Federal Got Aboard Instant Payments