When asked why Americans would trust a good deal of their finances to algorithms, Forrester Principal Analyst Peter Wannemacher likes to begin his answer by telling a story about his in-laws. Decades ago, the couple bought a TV set, and the salesperson offered them a remote control, which at the time was an option you paid extra for.

Husband and wife looked at each other, and responded, “No. Do you think we’re too lazy to get up and turn a dial?”

Of course, now we control everything by remotes, or by special mobile phone apps. We reason, if the technology is there and makes life easier, why not use it? Clearly, few people worry anymore that they’ll be considered lazy because they leave a task to technology.

In fact, “for more than a century, firms have been building better mousetraps for customers,” a recent Forrester report states, “but now, many are promising to catch the mice for the customer.”

Banking Transformed Podcast with Jim Marous

Listen to the brightest minds in the banking and business world and get ready to embrace change, take risks and disrupt yourself and your organization.

The New AI: A Banker’s Guide to Automation Intelligence

Manual tasks across channels is costly. And while AI is hot, there’s a simpler way to bring efficiency that many bankers have overlooked.

Read More about The New AI: A Banker’s Guide to Automation Intelligence

Algorithms Will Run Banking’s Future

This thinking now encompasses consumers’ use of apps that apply algorithms to many common financial challenges and chores. In the report, which traces the use of algorithms to manage our financial affairs, Wannemacher and other Forrester researchers noted that many such apps manage fairly narrow areas of our financial lives, but that this will evolve.

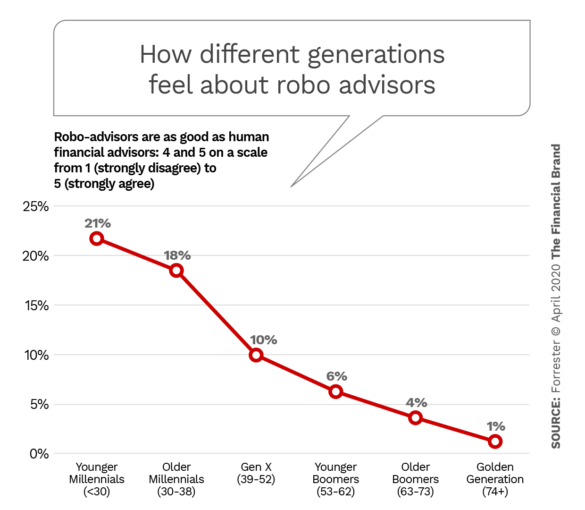

As a consumer survey by Forrester found, the younger people are, the more likely they approve of and trust a roboadvisor to handle their investments. Taking this as a proxy, Americans will increasingly be willing to have algorithms that have been fed their personal data alert them to financial issues on all fronts, not just in regard to banking. The better the technology “knows” them, the better it can serve them.

Forrester refers to this technology broadly as “autonomous finance,” which the report defines as “algorithm-driven services that make financial decisions or take action on a customer’s behalf.” Much as people will come to trust autonomous cars someday, consumers increasingly will trust the financial equivalent.

The report advises financial institutions to get into the game now, if they haven’t already. As algorithms take over more functions, the lines between banks and credit unions, insurance companies and fintechs will continue to blur. Those who don’t participate risk falling behind or becoming irrelevant.

“While the technology to deliver comprehensive automated financial advice or dynamic insurance underwriting is not yet ready, you can start with experimenting in single product areas or experiences today,” the report suggests. The key is to find some pain point and work at an algorithmic solution. The report makes clear that this will be an ongoing process once it’s started. These tools cover both the consumer and business sides of banking and intersect with other trends driving change. These include the internet-of-things, artificial intelligence and other automation.

Much of this development will hinge on cooperation with fintechs. But the report makes the point that fintechs don’t own this area exclusively. Large banks’ R&D functions have been developing such functionality as well, so that will keep the momentum going.

Forrester research indicates that one out of three consumers surveyed trust an algorithm to make at least one type of financial decision or action. Further down the road, as artificial intelligence becomes more adept, the report predicts, tools such as “digital financial assistants that offer more holistic advice and dynamic execution across financial products, connected devices, and suppliers will surpass today’s single-product focus.”

Forrester doesn’t see this trend strictly as aiding people with many financial relationships to manage. The report lays out potential use cases. One of them concerns a woman small business owner who periodically struggles with cash flow. Autonomous finance could monitor her accounts and automatically provide microloans based on present numbers evaluated against historical trends.

Algorithm-based approaches will appeal not only to consumers but also to busy small business owners and operators. Wannemacher notes that small firms on average have to juggle a dozen different financial services in order to run their firms, none of which have anything to do with the actual business they are in. Algorithmic services such as Xero, a cloud-based accounting platform, can pull everything together.

“In the wake of the pandemic, small business owners have one job — to make sure that their business survives,” says Wannemacher. Having such tools in place already would be handy.

Read More:

- Artificial Intelligence, Algorithms, Big Data & The Future of Banking

- Banks Losing Customers Who Want Seamless Digital Experiences

- Big Tech Firms Push Further Into Banking With New ‘Super Apps’

- How Personalization Strategies Can Backfire on Financial Marketers

COVID-19 Won’t Stop the Advance of Algorithms

As much of a game-changer as the iPhone was, no one outside of Apple and perhaps some sci-fi fans knew they needed one, says Wannemacher. Yet when the iPhone and the iPad came along, they made many solutions possible. In much the same way, people know that their financial lives don’t quite work consistently. They manage a diverse assortment of financial products and relationships that follow structures going back decades, and juggle more than their parents or grandparents did.

“Consumers need a better way to manage their financial affairs but aren’t able to articulate the product that would help them do so because autonomous finance services are still in their infancy,” the report says. In some ways the “pain points” of the business arise because traditional services grew out of how banks and credit unions organize their operations, rather than on how consumers try to meet their needs.

In this country and overseas a body of algorithm-driven apps target specific needs. Some, such as Dave and Even, handle such tasks as monitoring cash flow into and out of transaction accounts forecasting overdrafts and analyzing spending and savings trends in order to offer advice. Others, such as Tally and Zero, track and manage credit card accounts and may help the consumer improve their repayment efforts, to curtail debt. Such technical assistance has become available in the mortgage, payments, savings and investments areas, among others, according to the report.

Wannemacher believes the momentum of this trend is sufficient to overcome the braking force that the coronavirus is having on other aspects of finance. He thinks that now that more consumers are growing comfortable with digital products that this will accelerate their interest and acceptance of algorithm-driven services. He believes that more services considered part of “banking” will become embedded in other services, overlaying processes that formerly required manual action. Institutions in these cases will become wholesalers, in a sense, hidden but key to functionality. Those who don’t adapt to such changes may be left behind as traditional structures fragment and become à la carte affairs.

This is not to say that just inventing an algorithm and wrapping an app around it will be a ticket to success.

“New kinds of services will still have to prove themselves,” says Wannemacher. The report points out that some won’t work well enough to make it, and others have found it necessary to cover people for their costs when a product errs.

“For example,” the report says, “Digit has developed a range of features that prevent its automated savings tool from causing an overdraft, but the firm will also reimburse fees when this happens.”

The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic has prompted a pullback by some venture capital sources from funding fintech developments. Wannemacher says some strong candidates may lose the funding they need to get off the launch pad. Those that can still attract potential backers may have a tougher task now, he says.

“I don’t want to get too Darwinian,” says Wannemacher, “but you’ll have to really demonstrate value.”