Let’s get one thing straight: Google is not a democracy.

Google can — and does — change the rules at any time, without warning, and with basically no opportunity for feedback or debate.

“Nobody governs Google,” says Michael Bertini, Senior Director, iQuanti, and a veteran SEO expert. “They are in total control.“

So when Google rolls out changes to its algorithm, website mangers are often left scratching their heads. Will they get more traffic or less? What should they do differently?

A good case in point is Google’s Site Diversity policy, which debuted in June 2019. (Note: “Diversity” in this context has nothing to do with the social equity sense of the word. It concerns the number of sources that Google will display search results from.) Google says they heard complaints that search users were seeing too many listings from the same site in the top results. Their Site Diversity policy was established to ensure more variety in the results.

How It Works:

The site diversity change means that you won’t see more than two listings from the same site. Search for any bank or credit union in the U.S., and you won’t see more than two results associated with the domain (URL) maintained by that bank or credit union.

Unfortunately, there isn’t really any good way around it either. Google says they may still show more than two results from one domain in cases where their systems determine it’s especially relevant to do so, but don’t hold your breath. And if you’re thinking you might try to circumvent their policy by using subdomains, think again.

“Site diversity will generally treat subdomains as part of a root domain,” explains Google. “Listings from subdomains and the root domain will all be considered [part of] the same single site.”

Industry Cloud for Banking from PwC

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking applies our deep industry knowledge to your specific business needs

Unlocking Digital Acquisition: A Bank’s Journey to Become Digital-First

This webinar will offer a comprehensive roadmap for digital marketing success, from building foundational capabilities and structures and forging strategic partnerships, to assembling the right team.

Read More about Unlocking Digital Acquisition: A Bank’s Journey to Become Digital-First

When Google Made Its Site Diversity Move

The Google search engine has many tools for adjusting search parameters that many users never explore. Most people pop in a quick search and accept what Google delivers as research gospel.

In fact, much of what’s on the typical Google page is designed for the person who wants a quick answer to something. And in that regard, the Site Diversity policy works well for those who are just searching for reviews of consumer products (e.g., “best big screen TV”). However, this “equal opportunity” policy aimed at leveling the playing field could have serious consequences, and not just for marketers.

Consider, for instance, if you are a heart surgeon looking for the latest insights on “vasopressin for vasoplegic shock,” do you really want to see only two results from the Journal of the American Medical Association? Only two results from the American Heart Association? And only two results from the Cleveland Clinic, the world’s leading cardiology center?

Why It Matters:

Google’s Site Diversity policy has changed the fundamental nature of organic search: the results that Google doesn’t get paid for (but which are nevertheless far from “free”).

A report on the new policy by Searchmetrics.com compared organic rankings for thousands of keywords before and after the change.

The research found that searches producing more than three URLs from one domain in the top ten were “effectively zero,” a decrease from 1.8%. Searches producing three URLs from one domain occurred for 3.5% of keywords, a decrease of about half. Looking at searches producing two URLS from one domain, that was up to 44.2%, a slight rise from before the change. The evaluation found that in just over half (52.3%) the searches, the top ten all came from multiple domains, an increase from the pre-shift level of 47.9%.

Other parts of the test found that in certain niche areas, Google still favored “relevance” over diversity. (Interestingly, searches for recipes were one area where multiples were still common.)

“We still see SERPs where one site dominates, and that story didn’t change much after the update. That said, these six to ten-count SERPs are fairly rare” now, wrote Moz after the site conducted its own test. (SERP stands for “search engine results page.”) It noted that where Google appeared to have significantly violated its policy, it was the search terms that cause that. For example, naming a specific store or ecommerce site in a search can make many or all of the listings specific to it.

Read More:

- Google’s Vision for the Future of Bank Marketing, AI, and Data

- How Google Keeps Changing Financial Marketing

- Pro Tips to Improve How Google Ranks Your Banking Website

How The Diversity Shift Impacts Financial Brands

Bertini points out that some of his financial services clients have actually benefited from the shift in policy. Now that many heavy hitters have found their presence on the first page of search results to be “rationed,” in a sense, that frees up first-page listing space for organic listings from others. Some of those companies are seeing more first-page listings than they have had in the past.

However, there are many types of searches Google users perform. For some, a more diverse mix of sources may sound good, and sound fair, but from the viewpoint of actual utility, is less useful.

Reality Check:

For some queries, the site diversity policy eschews many of the most relevant results from authoritative sources in favor of variety, meaning users might not see what they really want: the best results.

Further, in some ways Bertini feels that companies that have spent huge amounts developing high-quality content and tailoring their pages to fit Google’s quest for relevance are being treated unfairly. Other brands now gaining first-page exposure are essentially receiving “free money,” he says — exposure they didn’t work for.

“It’s like getting a participation trophy,” says Bertini.

What Site Diversity Looks Like In Practice

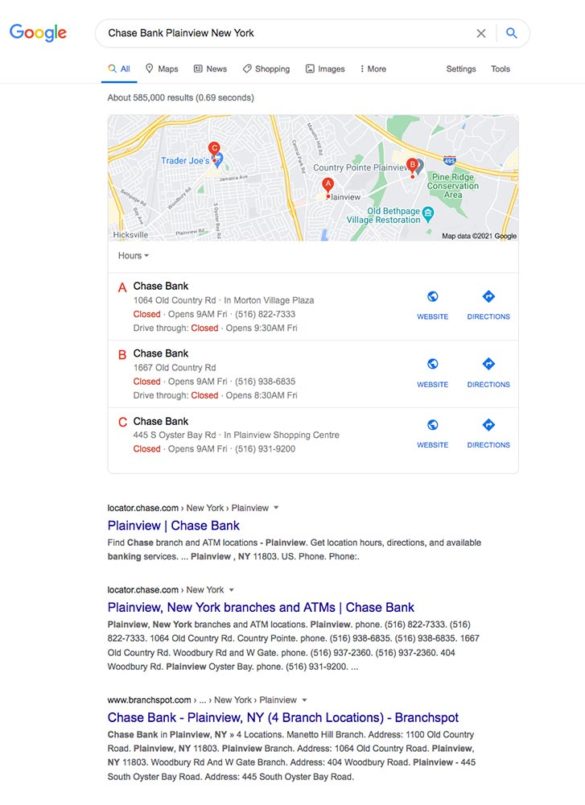

In the search below, The Financial Brand searched Google for Chase Bank branches near Plainview, a suburb of New York City. In the result shown below, Google first produced some locations on an area map, then two URLs appear from the Chase branch locator pages on its website. From that point on (past the point where the illustration ends), there are two listings from Branchspot, one from MyBankTracker, one from Mapquest, one from WheresMyBank, one from Bank Branch Locator, one from US Bank Locations, one from Yelp, and so on. It’s a definitely a diverse mix, thanks to Google’s Site Diversity policy, but are these really the results most users would want for that search?

Now let’s test another common search — “best checking accounts” — using both Google and two other search engines: Bing and Duck Duck Go. Here’s what we get…

- Paid ads from Capital One, TD Bank, Bethpage Federal, and the BestMoney comparison site.

- Organic results for NerdWallet, BankRate, Forbes, U.S. News, Business Insider, The Ascent/Motley Fool, ValuePenguin/LendingTree, CNET, The Balance, MagnifyMoney.

- Three more paid ads from M&T Bank, Citibank and Betterment.

- No cases of multiple URLs from same site at all.

Duck Duck Go

- Paid ads for SimplyCents, Capital One and DepositsAccounts/LendingTree.

- Organic results for Forbes, NerdWallet, Bankrate, SmartAsset.com, Motley Fool, CNET.

- A gallery of ten videos on the subject, all from YouTube.

- Listings from U.S. News, CNBC, I Will Teach You To Be Rich, Clark Howard, Money.com, Nerdwallet (again), Bankrate (again), The Balance, Go Banking Rates, Magnify Money, The Penny Hoarder, Money Crashers (twice in a row), CNBC, MoneySense, Kiplinger, Crediful, Millennial Money, Investopedia, Forbes (again).

- Four cases of multiple entries from same site.

Bing

- No entries were labeled as paid ads.

- Capital One, Wells Fargo, Online Banking, PenFed, DepositAccounts.com.

- A focus box of thumbnail rankings from four sites (Yahoo Finance, MoneyCrashers, Crediful and Good Financial Cents).

- Forbes, NerdWallet, Bankrate, Motley Fool.

- A gallery of videos.

- Consumers Advocate, NerdWallet (again), Penfed (again), and Capital One (again)

- Three cases of multiple entries from same site (though at least one pair may reflect unlabeled ads).

A search like this (a “best of …” hunt) is the type of query that would have usually been dominated by one of the aggregator or comparison sites. NerdWallet, for instance, is a site that used to get such exposure before Google’s site diversity shift. Search for other financial “bests” — savings accounts, credit cards, personal loans, business loans, card rewards — and you won’t see more than two organic listings from the same site now. On some you will see doubles, but not triples. And (shock!!) some search engine results pages for these queries are heavily littered with paid listings.

According to Bertini, some search terms that used to trigger only organic results now trigger paid listings. Paid listings only pay off when both seen and clicked on, and Bertini thinks Google is doing a bit of double-dipping: driving greater diversity, and drumming up more money in the process.

What About Smaller Financial Institutions?

While larger banks and card issuers can afford massive programs like those run by Bertini’s firm, the consultant says the cost is beyond the reach of smaller institutions — those now realizing that they aren’t getting the exposure they used to.

However, an alternative and affordable strategy can help. This requires beefing up the smaller institution’s website content. Beyond adding more and better content, he recommends diversifying the range of topics that an institution’s site covers with its content. The idea, using a fishing analogy, is to increase the number of hooks and the number of ponds where the brand can engage with more types of searches.

Another strategy is to look for keywords that can narrow a search to your institution’s locale. For example, a bank offering home loans could aim to capture keywords including mortgages, their community location and other points.

Going to keywords in volume won’t work for smaller players because large institutions can simply spend a lot more. “You have to be very strategic in your choice of keywords,” says Bertini.

In fact, Google itself has stressed to companies that the best way to meet the challenge of any of its updates is to offer the best content possible. In noting that, a blog on Seer Interactive’s site recommends asking these questions:

- Who is the intended audience for my website?

- What are they hoping to find if they visit the site?

- What are some of the factors that impact their purchase decision?

- What supporting content could be helpful for them to know?

- What do they need to see at the top, middle, and bottom stage of their search?

- What on my website could frustrate the user and force them to leave?

How Banking Execs Can Refine Their Search Results

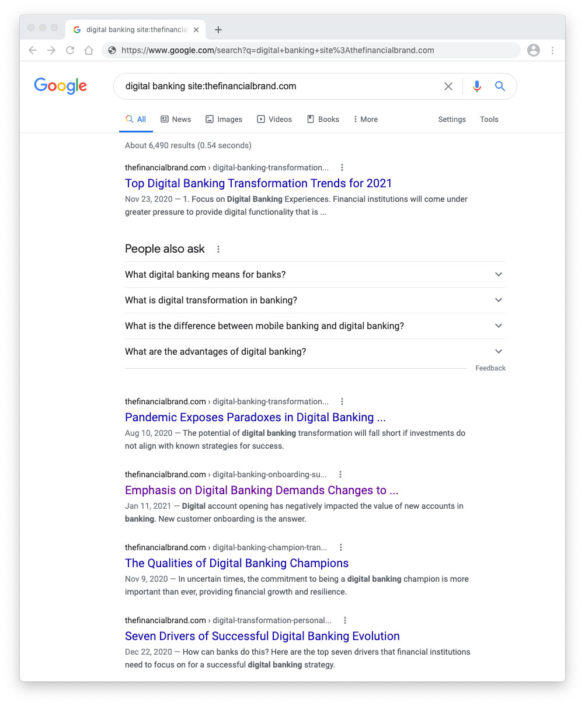

While searching Google is often helpful when you have no idea of where to look, sometimes you may know where your results should come from. If, for example, you wanted some new ideas for “deposit growth strategies”, you could search Google and take your chances with a variety of sources displayed thanks to Google’s Site Diversity policy. But do you really only want two results from The Financial Brand? Fortunately there is a way to bypass the Site Diversity policy using Google’s site-specific search function.

Simply type in your search term, followed by the word “site:” then put the URL for the website you want to focus on, like this:

[search term] site:specificwebsite.com

The example below, which illustrates the technique, uses Google to find “digital banking” results only from The Financial Brand.