Most of you are genuinely nice, caring people who sincerely want to help other people who may be in need. Whatever.

But for too many of you, your view of what it means to be “unbanked” in America is off-kilter.

Bring up the topic of unbanked consumers, and it conjures notions of poverty-stricken, under-served and under-privileged people who have been “excluded” from the banking system by evil bankers who put profits before people. Let me wipe the tears from my eyes.

There are certainly people who fit the description I just laid out. But thinking that everyone who is unbanked fits the description is about as far away from reality as you can get.

I first wrote about a segment of consumers I call the Debanked–consumers who willingly opt out of the traditional banking product structure, and manage their financial lives with “alternative” financial products–back in October 2011.

Two and a half years later, too many of you nice, kind, caring people still don’t distinguish between the Debanked and the truly unbanked.

—————

In its latest report on US consumers’ mobile banking activities, the Federal Reserve cited the reasons why the Unbanked are unbanked (if you won’t believe my research numbers, maybe you’ll believe theirs).

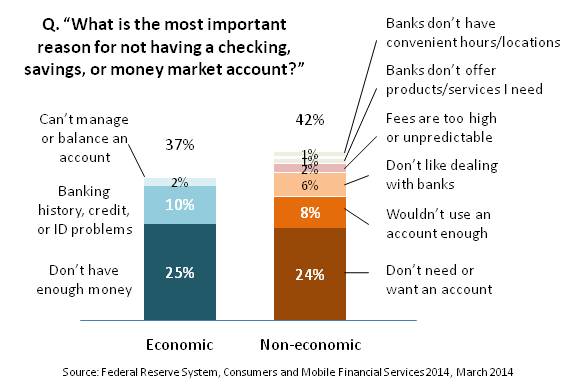

I re-categorized the answers into three buckets: 1) Economic reasons, which reflect a consumer’s economic ability to have a bank account; 2) Non-economic reasons; and 3) Other reasons (the “other” and “refused to answer” responses from the Fed study).

Among consumers who are unbanked, a little more than a third–37%–cited economic reasons for not having a bank account (and I’m being generous here, including “inability to manage/balance an account” as an economic reason).

More than four in 10 unbanked consumers, however, list non-economic reasons for being unbanked. Reasons like “I don’t need or want an account” or “I don’t like dealing with banks” or “Banks don’t offer the products/services I need” or “Bankers smell like dog poop” (I might have made that one up).

The Fed also reported that the number of people who are unbanked rose a percentage point, from 9.5% in 2012 to 10.5% in 2013. This will likely provide fodder for you really nice, caring people to further point out how the banking industry is further under-serving these poor, unfortunate, disadvantaged consumers.

But it is possible, however, that the increase in the Unbanked ranks is due to an increase in the Debanked, who willingly leave the traditional banking system.

You might also be tempted to say that a 1% change isn’t a very big number. But 1% represents more than 1 million households. That’s potentially 1 million households closing out their checking accounts for prepaid debit cards or other types of alternative products. (Side note: I wonder if Moven and Simple customers, who don’t have a checking account directly with a bank, consider themselves to have a bank account).

—————

Bottom line: Unbankedness is not the problem that many people want to make it out to be.

Reporting the unbanked numbers as a measure of “financial exclusion” is misleading. Voluntary exclusion is not the problem, involuntary exclusion is. According to the Fed’s numbers, involuntary exclusion is 3.9% of the population (37% of 10.5%). That’s less than the rate of unemployment.

It’s time to revise our definition of the term unbanked, and how we use it.