Demand for cross-border payments is surging as remittance flows rise, global supply chains deepen, and online merchants work to sell products in more countries. But, while real-time networks have made instant the norm for domestic payments, global transfers have been slow to catch up.

The cross-border payments market is expected to rise more than $100 trillion in the next decade, to over $250 trillion by 2027, according to a forecast from the Bank of England. Meanwhile, banks’ outdated core systems and international regulations are hobbling global transfers, with most funds moving through correspondent banks over several days in opaque transactions that can cost up ten times more than a domestic transfer.

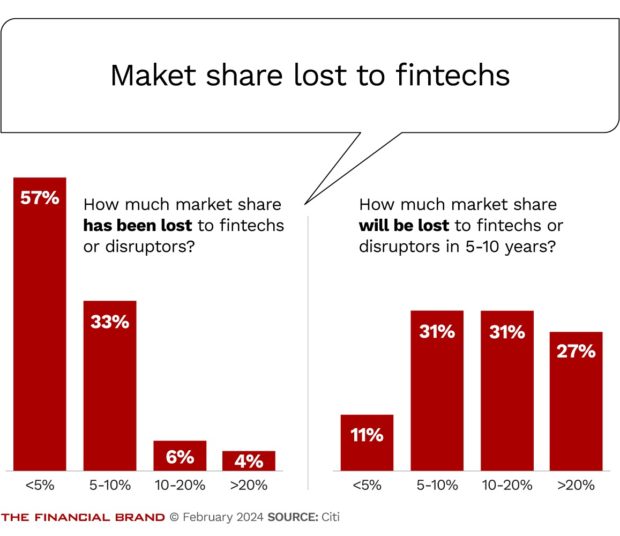

Fintechs like Wise, Ripple and Revolut have moved into this market with multi-currency payment apps and wallets that make cross-border payments faster, cheaper and more convenient. Banks have been slow to react. Already, over 40% of banks have already lost at least 5% of market share to fintechs, and 89% expect they could take at least another 5% in the next five to 10 years, according to a May Citigroup survey of over 100 financial institutions.

A Staggering Statistic:

The percentage of banks that have already lost at least a 5% market share to fintech competitors:40%

Legacy players continue to handle the business-to-business transfers that account for the lion’s share of cross-border payment flows and revenues. The problem is that digital companies are hooking consumers with cross-border payments, only to sell them more financial offerings, including loans, savings accounts and debit cards. That could help the disruptors take a larger share of customers’ wallets from banks, says Emanuela Saccarola, Global Head of Cross Border Payments at Citi.

“They hook them with the payments because there is a lot of friction in cross-border payments,” says Saccarola. “We have to warn our clients to be careful about losing market share. Once you have lost market share, it’s going to be a lot more difficult to get it back.”

Explore the big ideas, new innovations and latest trends reshaping banking at The Financial Brand Forum. Will you be there? Don't get left behind. Read More about The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th Achieve a better return on your marketing investment. Leverage behavioral data and analytics to target the right customers with the best possible offers. Read More about Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th

Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

A Digital Delay

Banks are notoriously slow to accommodate digital demand — with sometimes costly outcomes. Take the rise of online home loan lenders like Rocket Mortgage, now the largest U.S. mortgage lender. Nine years after the three biggest U.S banks’ handled almost half of all home originations in 2010, the digital disrupters had cost them roughly 30% of their market share.

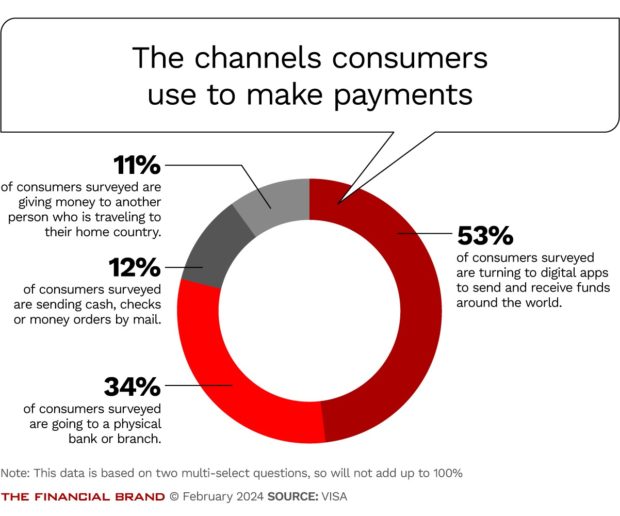

In cross-border, consumers are gravitating to digital providers in a market where ancient technology has long been the norm. Mobile apps have already become more popular than legacy systems among consumers who routinely send and receive funds in 10 key remittance zones, according to a March 2023 survey from Visa.

Many mobile payment apps are hoping to go further than payments. Revolut, which started as a mobile payment company, has stacked on dozens of financial offerings in a bid to become a ‘super-app’. Meanwhile, Ripple, which started out as a crypto payment rail, has been exploring links between digital payment offerings in multiple currencies.

Already, some banks are worried that the digital competitors could start to handle a larger share of consumers’ wallets. In January, HSBC launched Zing, a competitor money-transfer app built for users who are not enrolled with the bank. The app’s strategy is to sell consumers on one financial touch point before making them stay with others — a sign the bank is responding to the fintech threat by mimicking their strategy.

“I think a lot of the banks have been slow in coming to terms that this was a real threat,” says Citi’s Saccarola, who says some banks in Asia have already lost as much as 75% of their market share to fintechs in the cross-border market. “It’s not the time to be relaxed.”

Read more:

- How Apple Can Grow in Financial Services Without Becoming a Bank

- 8 Themes That Will Power a Fintech Comeback in 2024

Do Banks Buy, Build or Back Out?

Banks have long surrendered ground to others in markets like FX and cross-border remittances. There are good reasons for their reluctance, says Gareth Lodge, a senior analyst for payments at Celent.

Even as fintechs have eaten into the high margin C2C and C2B share of that revenue pie, banks continue to dominate the B2B cross-border payments that make up the largest share of global payments. RTP networks could change those money flows. But the biggest players are likely to stay the same, says Lodge.

“I would imagine, most people would trust a Citi or HSBC to send $100 million,” says Lodge. “Would I trust an unregulated fintech? Probably not.”

Anyway, banks often lose money on small value transactions, which they may have to funnel through the same sluggish channels as multi-million-dollar corporate transfers. Bankers could even benefit from passing on low-value transactions — which are often transacted between unbanked migrants — to fintechs that make help make global transactions more transparent, Lodge says.

The upshot is that global banks like HSBC are more likely to wrestle back lost gains from digital competitors, says Thad Peterson, a strategic advisor for Datos Insights. Smaller banks are unlikely to justify the same investment.

“Large banks like HSBC or Citi — true global players — there’s an opportunity for them. I think those guys will probably compete,” says Peterson. “But, by and large, banks are going to stick to their core guns.”

U.S. banks will have a harder time than most entering the race toward real-time international payments. While digital transactions are the norm in Asia, Europe and other continents, paper cheques are still common in the U.S.

The launch of real-time networks like The Clearing House’s RTP rail and The Federal Reserve’s FedNow have helped level the playing field. But many banks continue to operate with processing systems built over 40 years ago and transfer money through overnight batch payments, making it harder for them to connect to global payment messaging standards like ISO 20022.

“Large banks like HSBC or Citi — true global players — there’s an opportunity for them. I think those guys will probably compete. But, by and large, banks are going to stick to their core guns.”

— Thad Peterson, Datos Insights

As mobile transfer apps become more competitive, banks that handle global payment flows might still benefit from striking up partnerships with financial providers that already enable faster global payments, says Citi’s Saccarola.

Some banks have already opted to work with the fintech competitors, such as London-based Barclays, which recently teamed up with TransferMate. Application programming interfaces (APIs), which have begun to rise with the spread of open banking, provide the link. Others have worked with other financial institutions like Citi, which has begun using APIs to connect banks to different payment providers and facilitators, and JPMorgan, which has begun leveraging blockchain networks to transfer digital assets across borders.

Even if banks decide to back out of the cross-border space, there is an opportunity for them to offer perks, like travel insurance, for consumers who are abroad, says Lodge.

Players big and small have to stay alert to how fintechs are changing consumer expectations for faster, more convenient, digital transactions, says Peterson — even if they aren’t going to be leaders.

“Bankers are definitionally conservative. It’s going to be the startups that make the needle move,” Peterson says. “The banks will follow.”

Charles Gorrivan is a contributing writer at The Financial Brand. In the summer of 2023, he covered the financial services industry for American Banker through the Dow Jones News Fund Business Reporting Program. In 2022, he reported on the New York governor’s race for Gotham Gazette.