For a few months early in 2021 it looked like U.S. consumers discovered the value of putting money in the bank. However, the raw statistics proved misleading. Americans, as soon as they could, reverted to their old, paltry savings habits. It’s a trend with broad implications for the banking industry, which generally is still awash in deposits.

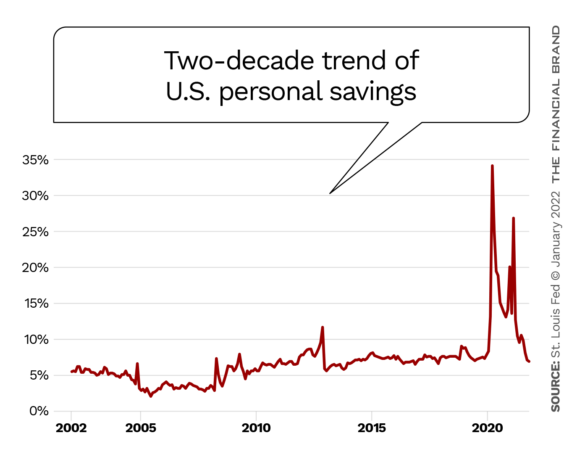

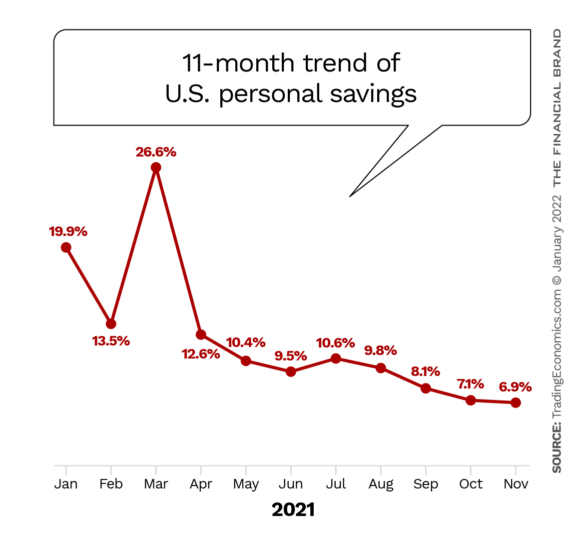

As the first pandemic year came to a close it seemed that consumers finally had realized the wisdom of socking away money in bank accounts. The nation’s savings rate spiked to almost 34% after decades of hovering between 3% and 15%. Then, after a brief dip, it spiked again at almost 27% in March 2021, according to data from FRED, the economic database of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Those to savings surges proved to be startling anomalies. The latest statistics show a steady decline in the savings rate, dipping to 6.9% in November of 2021. The idea that the pandemic brought fiscal conservatism to the nation’s families has proven illusory.

83% of FI leaders agree investing in AI is essential for 2024 but how you leverage AI is instrumental in success and meeting customer expectations. Read More about Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions Vericast’s 2024 Financial TrendWatch explores seven of today’s most critical financial services trends to provide a complete view of the current loyalty landscape. Read More about Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Why the Savings Numbers Were Deceiving

In fact, the pandemic, as bad as it has been for the health of the nation, has worsened the financial situation of the 131 million consumers who live paycheck-to-paycheck. They had very little, if any, extra money to save in the first place. By and large, they were not part of the savings surges.

Who saved, then? The 43% of the population who didn’t live on the edge and who had the wherewithal to put it somewhere safe, other than what they would have done with it – that is, spending on travel or eating out.

Two Different Worlds:

Much of the population had little money to save and the rest had no place to spend.

Then came the brief hiatus — before the Delta and Omicron Covid variants emerged — and some of those with better means found an excuse to try to catch up for lost time. Also, some of those same people, having lost their jobs, had to dip into savings to meet basic expenses.

There is a great deal of unevenness in consumers’ ability to deal with life’s unexpected shocks. This situation is recognized in data from a Pew Research Center report from March of 2021:

- A plurality of lower-income adults are saving less during the pandemic.

- A majority of lower-income adults who are not retired say the pandemic will make it harder for them to achieve their long-term financial goals.

- Many older Americans whose employment was affected during the coronavirus outbreak say they have or may have to delay their retirement.

- About three-in-ten Americans often worry about their debt and saving for retirement.

Read More: Trendwatch: Most People Now Making Mobile Deposits

Old Financial Habits Re-emerged

When the federal government flooded the economy with stimulus money in various forms in response to the pandemic, much of which went to pay bills while a considerable amount went directly to savings accounts, based on the recipients’ financial status.

“For some workers in their 50s and 60s who kept their jobs, saving money wasn’t necessarily so difficult during the pandemic,” says Bruce Horovitz, writing for AARP. “For them, basic pleasures like traveling and eating out became no-nos — and many also received hearty financial bumps from stimulus payments — so saving was easier.”

Fast Changing Behavior:

For a while it looked like the worst was over, Covid restrictions were loosening, inflation was creeping up, and many consumers became impatient to spend.

Despite the pandemic lingering on — and with omicron, becoming even more virulent — the spenders’ mindset and day-to-day necessities overtook the urge to save.

Pandemic fatigue took a toll on patience, especially when the Covid infection rates started to dip in the autumn of 2021 and restrictions started to ease. U.S. retail sales increased by 1.7% that October, according to Commerce Dept. figures.

Meanwhile, rising inflation has caused many to dip into savings for everyday expenses. The Federal Reserve raised its forecast for 2022 from 2.3% to 2.7%, although it expects that rate to dip in 2023.

“I doubt that there’s been any permanent shift in our savings behavior,” says Sam Stovall, chief investment strategist at CFRA Research, in an interview with NPR’s Marketplace. “It’s very hard for humans to change their stripes in the long term.”

“We’re spending like we used to, which means we’re saving less … again,” says Shannon Seery, a Wells Fargo economist during the Marketplace interview. “A lot of stimulus has begun to fade. We had enhanced unemployment benefits expire in September.” She adds that “inflation hurts, too. Pricier food and gas tend to chip away at the piggy bank.”

For financial institutions, the consumer savings rate through 2021 pumped up deposits sharply and even though the savings rate since has declined, financial institutions have held onto considerable sums. In September, FDIC reported that commercial banks and savings institutions collectively held $15.7 trillion in domestic deposits.

“Most banks are sitting on a pile of deposits and will be very hesitant to pass along higher yields to savers if they don’t need more deposits,” says Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate.

Read More: Are Banks & Credit Unions Losing Out on Savings Apps?

Don’t Take Things for Granted

Just as consumer behavior is changing such that people transition back to a pre-Covid lifestyle, banks and credit unions need to step up in their role as trusted counselor and service provider.

“Customers shouldn’t have to give up on their savings goals or assume that they have no control over their financial futures,” according to Personetics. “Banks should take this opportunity to help people stay on top of their money, stay on track with their savings goals, and keep being proactive about improving their financial wellness.”

Specifically, financial institutions “should create and promote automated savings programs to help customers rebuild their savings and keep up consistent saving habits,” Personetics advises.

AARP urges its consumer audience to do just that: “Now is the perfect time to set up an automatic savings mechanism at a bank, brokerage, or mutual fund company.” Tellingly, this blog, published in May 2021 at the height of the savings anomaly, states: “This is important to do before the world opens up and we adopt all our old habits,” quoting Nicole Gopoian Wirick, founder of Prosperity Wealth Strategies.

Keep in Touch:

Deposit levels are ample now but financial institutions have to maintain customer relationships for when conditions change.

Ken Tumin, founder of DepositAcounts.com, who keeps close tabs on Federal Reserve meetings and decisions, dissected the December 2021 Fed rate hike statement with an eye for what savers should do in the new year. His ultimate advice: “For your safe money (with no risk to principal), a combination of I Bonds, reward checking accounts, online savings accounts, and CDs can still make sense.”

For financial institutions, “if deposit needs are negative, the emphasis has to be on exiting high-cost deposits ASAP,” writes Charles Wendel, Founder and President of Financial Institutions Consulting in his blog. “However, deposit needs will change, so strong communication to depositors explaining your change in appetite may help you reconnect with them later.”