About a month after Chase went national with its My Chase Plan, a credit card variation on the hot buy-now-pay-later trend, Capital One Bank announced it would bar transactions identified as “point-of-sale loans” charged on its credit cards, regardless of the lender. POS loans are another, older term for buy now pay later (BNPL) lending.

So what’s going on here? Do these two retail banking giants really have 180-degree views of the same market?

Not necessarily. Reuters first reported the Capital One decision and cited a spokeswoman as saying, “These kinds of transactions can be risky for customers and the banks that serve them.” Beyond that, the big retail bank hasn’t said much.

Some observers question whether Capital One is just trying to protect its credit card interest that BNPL providers are cutting into. Others, however, say, no, the bank is raising a legitimate issue, because paying off a BNPL purchase with a credit card is paying off debt with debt.

Capital One’s move, which applies everywhere except the U.K., only affects the use of its credit cards for BNPL transactions, not those tied to its debit cards or checking accounts. Overall, debit cards account for a larger portion of BNPL activity. Two of the most active fintech players, Klarna and Afterpay, report that about 85% and 90% of their transactions respectively are made with debit cards, according to Digital Insights.

This highlights a key point about BNPL: it is not monolithic. Brian Riley, Director of Credit Advisory Service for Mercator Advisory Group, breaks the BNPL field into two models: 1. the fintech model — the fastest growing segment — led by the likes of PayPal Credit, Klarna, Affirm, Afterpay, Splitit and many others, and 2. the bank model, with three large institutions being the main players in the U.S. so far. These are: American Express (Pay it Plan it), Citibank (Flex Pay) and Chase (My Chase Plan).

But within the fintech ranks especially there are many variations, some of which are interest-free, some not, some with late fees, some not. One thing they have in common is that they allow consumers to “buy on time,” to borrow a 1950s phrase, but in a very 21st Century way — near instantly at the point of checkout.

Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Vericast’s 2024 Financial TrendWatch explores seven of today’s most critical financial services trends to provide a complete view of the current loyalty landscape.

Read More about Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Why Industry Cloud for Banking?

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking helps deliver personalized products and services that today’s customers expect.

Differences Between Fintech and Bank BNPL

The fintech BNPL model, in a nutshell, is a tech-driven means for consumers to opt to pay for a product in installments, usually within a specified range of time. As Simon Taylor, Co-Founder and Head of Ventures at 11:FS describes it in a blog, “BNPL providers are masters of great checkout experiences.” Fintech providers tend to work directly with merchants, often embedding the BNPL option on the merchant’s online checkout page, mobile app, or as a button on an in-person screen.

“Bankers miss that BNPL [as conducted by fintechs] is more of a merchant play than a consumer play,” says Mercator’s Riley. A key selling point, he adds, is the “seamless, slick integration by companies like Afterpay at retailers such as the Gap.”

Bank BNPL models at present are mainly credit-card based. “The installment option is offered to the buyer after the purchase is made, typically via a targeted communication from the issuer via the online banking app,” notes The Futurist Group in its Payments Disrupted report. The research firm believes that going forward more banks and credit unions will work with fintechs to allow the traditional players to introduce installment options at the point of sale, putting them on an equal footing with the fintech BNPL providers — covered further, below.

Paying in Installments Isn’t a Low-End Product

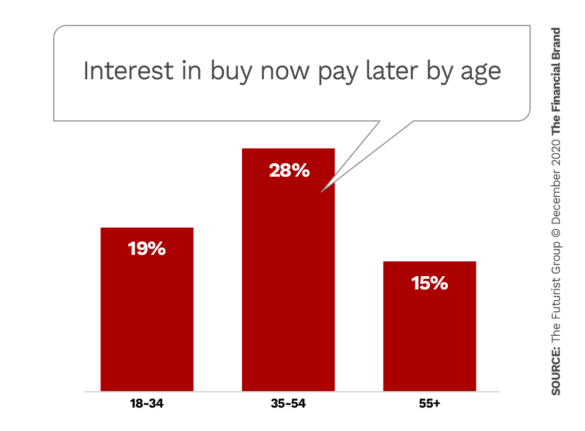

Although Gen Z and Millennial consumers as a rule love fintech apps like Venmo, BNPL apps from Affirm, Klarna, Splitit and other fintechs actually have stronger appeal among older Millennial and Gen X consumers. An earlier story on BNPL quoted a finding from Ascent that 37% of U.S. consumers between 18 and 54 have used a BNPL product. Data from The Futurist Group, based on more than 40,000 interviews in the first half of 2020, show a similar pattern.

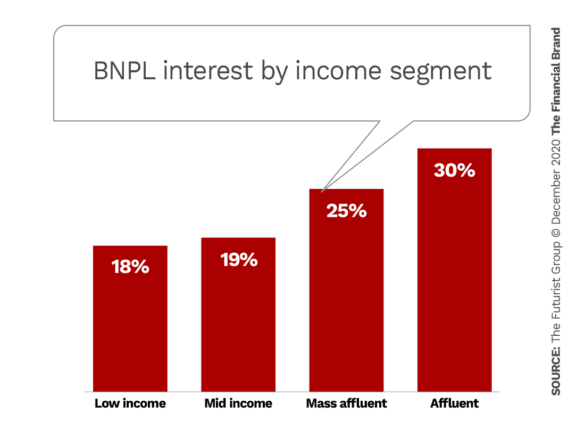

It’s also widely believed that BNPL skews lower in the income scale, appealing to consumers who can’t qualify for credit cards. Research by Cornerstone Advisors found that seven in ten BNPL users earn more than $75,000 and are highly educated. “The notion that consumers are using BNPL programs because they can’t get (or don’t’ have) a credit card is nonsense,” said Ron Shevlin, Cornerstone Managing Director of Fintech Research in a blog. The research found that 97% of these users have at least one credit card.

Data from The Futurist Group clearly shows greater interest for buy now pay later programs among more affluent consumers.

Risks and Regulation Getting More Attention

Go to the websites of some of the fintech firms and the message that comes across loud and clear is: “Want it? Buy it! There’s no interest and you can spread out the payments” — or variations on that theme.

As several people observed, that kind of instant gratification messaging was a staple of early credit card marketing for years. Now tightly regulated with many required disclosures, credit cards may be the model BNPL lenders will be held to eventually.

“If you can put steam on a mirror, you can qualify for these loans.”

— Brian Riley, Mercator Advisory Group

Right now, however, the terms of BNPL lenders are far from clear. Several of the plans do include interest, which, with some, will kick in if the consumer fails to make a payment.

Cornerstone Advisors found that over the past two years, 43% of BNPL uses have been late with a payment, based on its survey of consumers. Of those, two-thirds said it was because they lost track of when the bill was due, with the other third not having the money.

Being late doesn’t necessarily lead to a loss. 11:FS analyst Simon Tayler wrote that Afterpay reports an average of 3% of its loans falling into losses while Klarna comes in a little higher, at about 5% losses.

Taylor, who believes that BNPL is beneficial for the vast majority of consumers — providing a convenient way to smooth out payments — acknowledges that not all consumers may realize they’ve just acquired debt. “A checkout process that removes friction and makes you more likely to buy, is also one that needs to minimize the small print,” he states.

Most BNPL transactions only do a “soft check” on credit history, which is part of the reason Mercator’s Riley is a little less sanguine about the current state of the business. “If you can put steam on a mirror, you can qualify for these loans,” he tells The Financial Brand. He believes buy now, pay later is not a bad product, but it exists currently in a regulatory “gray area,” which needs to change.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which already has jurisdiction, will likely become more prominent in reviewing BNPL, Riley believes, particularly as a new administration settles in.

Bank Opportunities in BNPL – More than Defense?

Traditional retail banking institutions, with their foundations of trust backed by regulations, would seem to be in a solid position to challenge the fintech BNPL lenders. But why would they want to offer an option to customers that allows them to convert a credit card purchase into an series of fee-based installment payments after the fact?

“We saw the buy now, pay later trend as something our customers want. … Of course, you have to be willing to cannibalize yourself.”

— Marianne Lake, CEO, Chase Consumer Lending

Here’s what Marianne Lake, CEO of Consumer Lending at Chase said at a Bank of America Securities virtual conference regarding the bank’s My Chase Plan BNPL product:

“We saw the point of sale, installment lending, buy-now-pay-later trend as something that our customers want. It’s been well received, but it’s not a big driver of outcomes for us financially at this point. Of course, you have to be willing to cannibalize yourself,” Lake stated.

BNPL has the potential to cost Chase some revolving credit revenue, Lake acknowledged. “But we’re also seeing decent incrementality from customers who want this capability who otherwise were either not revolving or revolving less.”

The COVID-19 situation caused revolving credit, already in decline, to drop sharply, Riley points out. “That’s what institutions like Chase are looking to manage against” with their version of BNPL, he says.

Traditional institutions could have a further opportunity for in the BNPL market because funding could become an issue for nonbank lenders, as it did in the early days of marketplace lending. Fintechs advance the full amount of a purchase to the merchant (typically minus a discount and the initial payment), and carry the remainder of the loan for two to six months. Warehouse lines or securitization facilities can quickly dry up if loss rates climb.

Riley sums it up this way: “The bank card model is built on a loss rate of about 3.5%. Institutions like Capital One, Citi and Chase are masters of being able to price that accordingly.” But with fintech BNPL lenders who are putting people on the books really quickly without a lot of credit clarity, that’s really a big question mark.

“Lending money is a serious business,” Riley states. “Yes, you can bring in some cool factors, but you still need the ugly blood and guts that run the credit extension business to make this work.”

By contrast the bank BNPL models are dealing with already established customers, Riley continues. The customer just wants to tweak the terms a little and they’re actually inverting the typical request. They want to pay it quicker, instead of rolling it over. “So why not do that?”

Also important is that banks and credit unions make money not just from a credit transaction but from having the whole customer relationship. “That’s something that the fintech lenders lack,” Riley maintains. “They’re a one-trick pony.”