Deposits have been a major focus in the banking industry in the wake of market events such as the collapse of several large regional banks in the spring. After much hand-wringing about uninsured deposit levels and the proliferation of Federal Home Loan Bank advances, news coverage has started to zero in on a different type of bank funding: brokered deposits.

The use of brokered deposits by insured banks has been the subject of vigorous debate for decades. With the aggregate balance of brokered deposits held at U.S. banks approaching peak levels in recent months, it’s worth taking stock of what these deposits are, how they are used, and why this issue matters.

It’s also worth analyzing whether the increase in brokered deposits should be a cause for concern.

The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th

Explore the big ideas, new innovations and latest trends reshaping banking at The Financial Brand Forum. Will you be there? Don't get left behind.

Read More about The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th

The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Learn how to enhance your brand’s local visibility, generate more leads, and attract more customers, all while adhering to industry regulations and compliance.

Read More about The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

What Is a ‘Brokered Deposit’?

Brokered CDs date back to at least the early 1980s, when they were developed by broker-dealers such as Morgan Stanley as a means to offer insured deposits as an investment option through brokerage accounts. Insured banks offer the certificates of deposits in wholesale-sized blocks, which are then broken up into fully insured amounts (i.e., below the cap for federal deposit insurance) and sold by broker-dealers to their clients. The market for brokered CDs is time-tested and very deep, with outstanding balances exceeding $600 billion just a few months ago.

Federal law defines “brokered deposits” much more broadly to include not only brokered CDs, but “any funds obtained [by a bank], directly or indirectly, by or through any deposit broker for deposit into one or more deposit accounts.”

Common examples of “brokered deposits” other than traditional brokered CDs include sweep accounts, deposits acquired through deposit networks, and numerous other accounts where the bank relies on an intermediary to acquire customers.

However, whether an intermediary involved in acquiring deposits is deemed to be a “deposit broker” in a given scenario often requires a tortuous examination of facts and circumstances against regulatory criteria that are neither intuitive nor easily parsed.

Why Do Regulators View Brokered Deposits as Risky?

Regulatory experience with brokered deposits dating back to the savings and loan crisis (in the 1980-1989 era) suggests that banks with high levels of brokered funding are statistically at greater risk of failure and, when they do fail, are more costly to resolve.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. has conducted several studies to support this position, including this recent example. A key argument cited to explain the causal link runs along these lines. First, that brokered deposits are generally less valuable to would-be acquirers. Second, as a result, banks with meaningful amounts of brokered deposits that find themselves under severe stress are less likely to be acquired and thereby avoid failure. Third, once they do fail, the ability of the FDIC to find a purchaser is similarly diminished without a purchase price concession.

The ease with which banks can raise their own deposits through brokered channels, the often higher interest rates attached to them, and, in some cases, the lack of a direct relationship with the end customer, led to the view that brokered deposits don’t contribute to a bank’s franchise value and are therefore less valuable.

In addition to the FDIC’s view that brokered deposit reliance correlates with costly failures, regulators frequently assert that brokered deposits are less stable than deposits gathered directly by the bank. One reason cited in support of this view is that the customer’s relationship with the bank is weaker — and in some cases virtually non-existent — making the customer less inclined to maintain the relationship when alternatives are presented.

There’s also a view that customers who purchase deposits through an intermediary are more likely to be shopping primarily based on interest rate. The argument is that this makes them more likely to jump ship if the bank doesn’t continue to offer top-of-market rates. These factors combine to support the narrative that brokered deposits are a form of “hot money” that banks should only rely on as a last resort.

Read more: Does Banking’s Digital Focus Endanger Deposits?

Are the Regulators Right About Brokered Deposits?

There is data to support the FDIC’s view that heavy reliance on brokered deposits historically correlates with bank failures. However, correlation doesn’t always equal causation. Moreover, the cause-and-effect link frequently cited by regulators could be partially attributed to a self-fulfilling dynamic whereby the notoriously negative regulatory attitude toward brokered deposits causes market participants to view them as inherently less valuable.

As noted earlier, the term “brokered deposits” covers a diverse array of deposit relationships and has evolved significantly, especially in recent years. The FDIC updated regulatory criteria used to define a brokered deposit just a few years ago in an effort to better reflect the modern deposit marketplace.

History May Not Be A Good Guide:

Historical data and regulatory experience regarding the role of brokered deposits in bank failures may be less salient today. In fact, recent evidence from the bank failures earlier this year suggests that historical assumptions about brokered deposits may, in fact, be flat out wrong.

Brokered deposits actually proved to be more stable than supposed “core” deposits during the bank run that led to the collapse of First Republic, according to an analysis in another publication by my colleague Brian Graham. As depositors optimize for yield and security, rather than just convenience, fully insured brokered deposits have proven to be not only attractive but sticky, contrary to the historical “hot money” label.

In fact, quite recently, in a speech, Travis Hill, FDIC vice chairman, citing the experience at Silvergate Bank, which entered voluntary liquidation, stated that:

“From the FDIC’s perspective, the main downsides to brokered CDs are that they are costly for the bank and have no value in resolution. The flipside is that because the depositors have no relationship with the bank, earn high rates, are fully insured, and generally cannot withdraw before maturity, the deposits are extremely sticky, and the depositors are indifferent to whether the bank has a future or not. Far from being ‘hot money,’ these deposits are so cold they are virtually frozen in place.” [Emphasis added.]

Whether this is merely an observation or a signal of sorts remains to be seen.

Read more on deposit options:

- ‘It’s Like a Spigot:’ How SaveBetter Helps with Bringing in Deposits

- How This Fintech Offers Banks Cheap Deposits & Depositors Big Returns

Why Are Brokered Deposits a Hot Topic Right Now? And Is the Spike in Brokered Deposits Cause for Alarm?

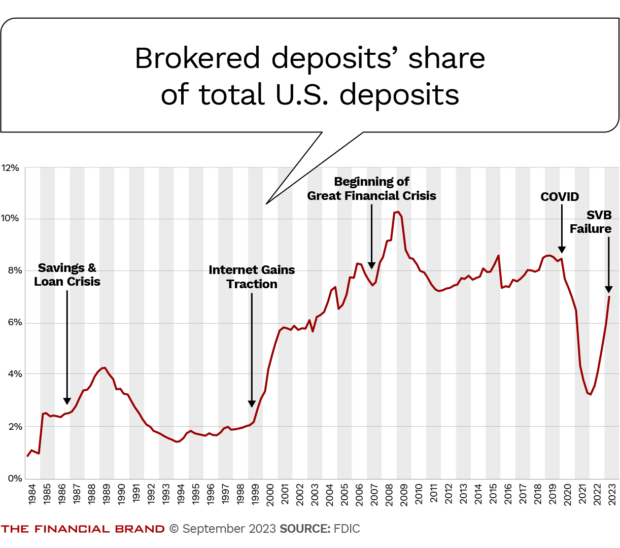

The Wall Street Journal reported in mid-September that the level of brokered deposits has spiked 86% in the past year. The aggregate reported balance of brokered deposits held by insured banks at the end of the second quarter was more than $1.2 trillion, which is near all-time highs on a nominal basis.

Given overall negative regulatory attitudes toward brokered deposits as a funding source, and broader concerns about the health of U.S. banks, it is natural for people to question whether the recent trend is cause for alarm.

However, the recent uptick in brokered deposits may merely reflect prudent bank treasury management practices on the supply side, with higher interest rates and concern over uninsured deposits driving consumer demand.

In addition, consider that, in some respects, the level of brokered CDs may also mark a return to norms preceding the Covid-19 pandemic. Although the aggregate level of brokered deposits is only slightly off record highs, it is still lower than just a few years ago. More importantly, on a relative basis, the amount of brokered deposits as a percentage of total domestic deposits is still significantly lower than all-time highs and well below the average over the past 20 years.

Reality Check on Brokered Deposits:

Banks remain less reliant on brokered deposits than almost any time since the growth of internet banking — with the exception of the anomalous Covid-19 period when federal stimulus flooded banks with deposits.

Read more:

- Chase Defends Branch Strategy as Deposit-Gathering Machine

- Are You Fighting Yesterday’s Checking Account War Instead of Today’s?

What Should Banks Be Doing About Brokered CDs, in the Wake of These Developments?

Bankers reviewing their wholesale funding strategies are in the unenviable position of weighing prevailing regulatory attitudes against their own needs.

A bit of perspective: Part of the recent trend in banks’ brokered deposit usage may reflect a desire to reduce reliance on other forms of wholesale funding that may also be disfavored by their regulators.

For example, many banks loaded up on FHLB borrowings in response to funding pressures caused by interest rate hikes and the Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failures. This led to consternation among some regulators and other industry observers.

Brokered deposits provide an alternative source of funding that does not require banks to encumber their assets — FHLB advances are secured borrowings — and has proven to be quite stable in today’s environment.

It’s important to bear in mind that brokered deposits can be essential components of a successful and sustainable funding strategy. The FDIC has acknowledged this, having concluded in 2019 that its own statistical analysis demonstrated “brokered deposits can be substituted for other bank liabilities without any statistically measurable effect on a bank’s failure probability” — assuming that the bank’s leverage ratio, core deposit funding and asset risk characteristics are held constant.

For example, brokered deposits can be part of an asset-liability management strategy that helps mitigate duration and interest rate risk or be used to replace less desirable funding. Brokered deposits can also be part of a temporary solution for de novo banks, or healthy well capitalized banks with a growth-oriented strategic pivot, to fund initial growth. The idea would be that they would taper off as core deposits replace the temporary funding.

See all of our latest coverage on the topic of deposits.

Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Achieve a better return on your marketing investment. Leverage behavioral data and analytics to target the right customers with the best possible offers.

Read More about Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Vericast’s 2024 Financial TrendWatch explores seven of today’s most critical financial services trends to provide a complete view of the current loyalty landscape.

Read More about Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

What’s the Main Takeaway?

Not all uses of brokered deposits are inherently risky. They are a tool, and like most tools, they can be quite effective and safe when used appropriately. Brokered deposits can also be misused or relied upon too heavily, which can indeed have calamitous results. Prudent planning, keen risk analysis and moderation are essential.

Bottom line: The recent rise in brokered deposit balances isn’t cause for alarm, at least not yet. But it is definitely a trend worth monitoring.

About the author:

Patrick Haggerty is a senior director at Klaros Group.