In the first of a series, The Financial Brand examines both the industry’s near-term challenges and opportunities, and charts a roadmap for both optimism and growth as the industry pivots into a new year.

Now that we’re into 2024, the banking industry faces a hard reality: Those who cling to outdated business models may struggle to remain relevant, while those who evolve and adapt may redefine their roles in the financial ecosystem.

Let’s consider some of the industry’s long-standing tenets and assess how they align with the evolving needs and expectations of customers:

Relationships are our edge: Traditionally, the strength of client relationships was the cornerstone of a bank’s identity. Yet, in an age where AI-driven hyper-personalization is the norm, will technological systems emulate the essence of human connection? Banks must discover the right balance between automated efficiency and the irreplaceable value of human touch.

Scale and stability are our strength: Perhaps not. The emerging reality is that agility often trumps size. Dynamic fintechs, especially those forging strategic alliances, pose a significant threat to their more established but less agile counterparts. Success for banks will hinge on their ability to adapt swiftly to customer needs, regardless of their size.

Regulation is our bulwark: While regulations have traditionally acted as the industry’s protective barriers, they can also stifle adaptability. However, completely discarding regulatory frameworks risks undermining stability. Banks must play an active role in shaping policies that balance fostering innovation while maintaining prudent oversight.

We must be all things to all people: The era of banks aspiring to be universal providers of all financial services may be coming to an end. Is it feasible for banks to excel at everything for everyone? A strategic focus on specialization and building partnerships may be the key to distinctiveness in a crowded market.

Technology will save us: While technology is a potent tool, it cannot single-handedly solve the deep-rooted cultural challenges that impede the evolution of banks. Actual progress demands a firm commitment to overturning established norms, setting the stage for a comprehensive digital transformation.

Industry Cloud for Banking from PwC

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking applies our deep industry knowledge to your specific business needs

Instant Messaging. Instant Impact.

Connect with your customers and provide lightning-fast support as effortlessly as texting friends. Two-way SMS text messaging is no longer optional.

How Our Customer Relationships Will Evolve

So as the banking industry looks towards 2030, the key question is: Will this era of change lead to a more customer-centric banking landscape?

To understand how far we may need to go to achieve the customer-focused bank of 2030, let’s turn to the current state of banking. In 2023, the average bank customer found themselves in a world where they no longer needed to physically visit a bank branch or engage directly with a human banker.

Thanks to remarkable technological advancements, tasks such as applying for a mortgage, opening a new bank account, or securing a loan could be accomplished seamlessly without face-to-face interactions. Automated processes have greatly increased efficiency and, for most customers, led to higher overall satisfaction. However, these changes were not without their complexities and some downsides.

Dig deeper: Solving the Mortgage Lending Challenge Through Smart Automation

Few would argue that a commitment to exceptional service is at the heart of the banking industry. The more knowledge bankers have about their customers, the better they can tailor their services to meet individual needs. An anonymous app user who opens an account and never engages with a bank representative represents a missed opportunity on multiple fronts.

Personal relationships and familiarity between bankers and customers were more common in decades past when bankers knew most customers by name. In 1950, for instance, the renowned real estate developer William Zeckendorf faced a dire situation.

Desperately needing $6 million in financing and with no more options in his Rolodex and exhausted credit lines, he paid an unannounced visit to David Rockefeller, a young vice president at Chase Bank and the nephew of the Bank’s chairman. The question on the table was whether Chase Bank would be willing to extend a $6 million loan that very day.

“In 2023, the average bank customer found themselves in a world where they no longer needed to physically visit a bank branch or engage directly with a human banker.”

Rockefeller not only approved of the deal but also had a personal connection and influence with Zeckendorf. However, the ultimate decision lay with Chase’s vice president of real estate. After some deliberation among the senior bankers, Zeckendorf walked out with a $6 million check, an amount roughly equivalent to $75 million in 2023 dollars. The story could be a master class in knowing your customer; a grateful Zeckendorf met his 5 p.m. deadline and promptly repaid Chase, in full, with interest.

Considering the compliance and technology hurdles, it’s challenging to envision such a feat occurring at any major bank today. However, according to Fletcher Jewett, founder of the strategic advisory firm Jewett & Co., such deals are still happening, but not at larger institutions. “With the right circumstances, I can always get those deals done for family offices with the community banks and non-bank financials because the large commercial banks are handcuffed right now. At the local level, they really know their customers.”

It may be more precise to say that the remaining local banks really know their customers. Jewett notes that the burgeoning costs of compliance and regulation have increased the velocity of mergers. In 1966, there were nearly 24,000 FDIC-insured commercial banks in the U.S. By 2008, there were 7,000; today there are approximately 4,000.

As consolidation continues to sweep through the industry, banking has undergone significant disruption from its historical roots. Assets have shifted away from traditional bank balance sheets, and fintech challengers and partners have emerged. According to McKinsey’s 2023 Global Banking Annual Review, over 70% of the growth in global financial assets since 2015 has moved away from traditional bank lending, redirecting towards private markets, institutional investors and the realm of “shadow banking.”

Inside the Looking Glass:

The major growth in banking is no longer happening in traditional bank lending — it's in the private markets and 'shadow banking.'

Mapping the Territory: The Current State of the Banking Industry

Despite the challenges posed by these transformations, the global banking industry remains a formidable and highly profitable sector. Statista estimates that total global banking assets grew from $130 trillion in 2010 to $183 trillion in 2021, a CAGR of rouhgly 3% from 2010 to 2021, implying assets will reach $200 trillion by 2024. Growth is being driven by a confluence of factors, including sustained worldwide economic growth, escalating asset valuations, heightened financial activity, industry consolidation, and innovative product offerings.

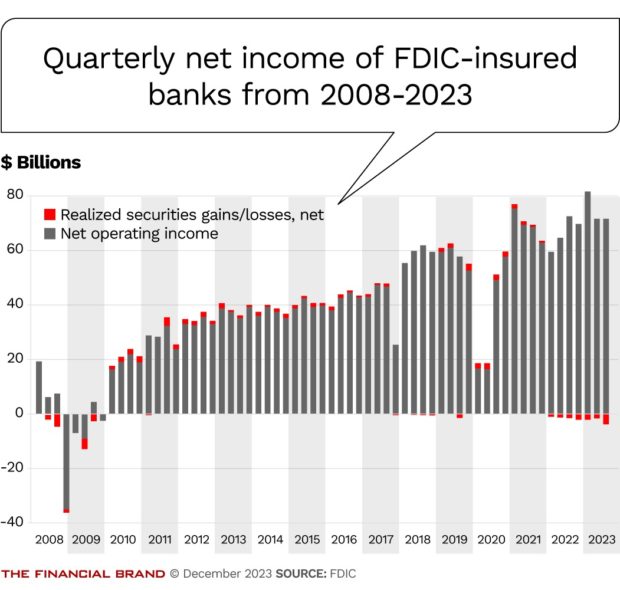

Within the U.S., FDIC-insured commercial banks reported an unprecedented aggregate net income of $279.1 billion in 2021, almost doubling the $147.9 billion in profits recorded in 2020. Through the first three quarters of 2023, net income was $219.0 billion, up 7% year over year. However, this impressive growth trajectory may face headwinds in the coming years as fluctuations in mortgage volumes, capital market volatility, and inflationary pressures potentially contribute to a dip in earnings.

Banks remain the bedrock of the financial ecosystem, offering essential services such as deposit facilities, lending, credit cards, payment processing, and wealth management. The top 10 banks on a global scale (the top four of which are based in China) held $37.8 trillion at the end of 2022, or approximately 20% of global banking assets, underscoring the ongoing trend of consolidation within the industry.

In the U.S., the quintet of JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, and U.S. Bancorp exercised dominion over $9.8 trillion in assets at the end of third quarter of 2023, which was equal to 45% of the $21.6 trillion in combined assets held by the largest 2,124 insured chartered commercial banks.

The Biggest Players Hold the Biggest Piece of the Pie:

The percentage of the global banking assets that the top 10 global banks hold:20%

Despite an increasingly competitive landscape, banks retain a trump card in the form of regulatory and legal safeguards. According to Ryan Gilbert, founder and chief of Launchpad Capital, a fintech-focused venture capital firm based in Oakland, “Banks cannot waver in their fundamental roles. That’s non-negotiable. If they deviate from that, they might as well relinquish their charter.”

Simultaneously, banks must remain adaptable in the face of emerging competitors and disruptive innovations. Gilbert remains optimistic, “The future of banking is bright, and that includes community banking.”

Read more:

- How One Community Bank Drove $135 Million in Deposits in 90 Days

- Community Bank Survival Requires a Hard Look in the Mirror

The Threat of the Fintch

Nonetheless, fintech firms have carved out significant market share, particularly among younger demographic segments. In the first six months of 2023, according to KPMG, investments in fintechs in the Americas rose to $36 billion, a 25% increase year over year. In the U.S., neobanks netted almost half of all new checking accounts opened in the first half of 2023.

Strategic advisor to payments firm Stripe, Patrick McKenzie, underscores, “There are structural reasons why banks find certain activities, though representing a small portion of their operations, unusually challenging.” He explains that banks often employ a tiered support structure, with initial tiers lacking the capability to address complex issues requiring escalation. While efficient, this approach can leave customers frustrated.

It is the legacy systems and entrenched organizational silos that frequently hinder banks’ agility in seizing opportunities. Every bank merger or acquisition tends to entail software and back-office integrations, which can invariably give rise to unforeseen complications.

The more piecemeal a bank’s systems, the greater the need for patches and the higher the likelihood of future breakdowns. A malfunction in these systems can bring a bank’s routine operations to a grinding half. This fact ensures that IT departments in banks are among the least likely to experience budget cuts during economic downturns.

“There are structural reasons why banks find certain activities, though representing a small portion of their operations, unusually challenging.”

— Patrick McKenzie, Stripe

Banks retain several core strengths despite many external and internal pressures, including regulatory safeguards, extensive customer bases, and relationships forged over decades. Moreover, they can safeguard their pivotal role in the financial landscape by capitalizing on opportunities in commercial lending, wealth management, and global expansion.

However, a failure to adapt to the evolving landscape poses a substantial risk. McKenzie aptly observes, “There are innovative ways to navigate this constraint, including adopting new technologies and business models.”

Yet despite the many challenges, banks find themselves presented with substantial opportunities. And the future of banking will be shaped by how financial institutions respond to the disruptive forces at play. Leaders within the industry will embrace change and position themselves to thrive amidst the prevailing uncertainties.

Next: Part 2 – The Seismic Forces Shaping the Industry