Do banks have an obligation to keep branches open, or will the need to cut costs drive an accelerated wave of new closures?

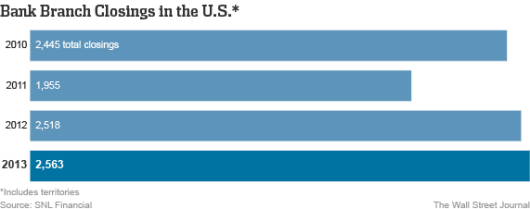

According to SNL Financial, banks closed a net 1,487 branches last year. That’s the highest number of net closures since the research firm began tracking the statistic in 2002. The majority of these closures have been attributed to the increasing use of online and mobile banking as technology enables consumers to manage their accounts, make remote deposits and shop for services more efficiently from desktops or smartphones.

Despite these closures, the number of bank branches in the U.S. still hovers above 80,000 according to the FDIC, making the U.S. one of the highest branched countries per capita in the world. That is why, in an era of sluggish revenue growth and heavy compliance costs, most bankers are trying to close or reconfigure underperforming branches as quickly as possible.

But closing branches involves more than just locking the doors and informing customers of other banking and branching options. In conversations with banking executives from seven of the largest banks in the country, I was told that between 50 percent and 80 percent of all branches that should be closed based on financial considerations are not closed due to potential regulatory or public relations repercussions. With many analysts saying that 25-30% of all branches are unprofitable, this could represent a ‘backlog’ of well over 10,000 branches nationwide.

In my discussions with these banks, it was mentioned that many of the branches that are not carrying their weight from a revenue perspective are either in lower income markets or in small rural areas where access to an alternative nearby physical location may be limited. This creates a unique dichotomy between a prudent financial decision and the desire to maintain trust and goodwill lost during the financial crisis.

When I asked whether reconfiguring these underperforming branches was an option, many of the executives I contacted said that they were even concerned about negative reaction to replacing tellers with automated kiosks or moving to smaller physical footprint locations. Said one banker, “We’re caught between a rock and a hard place with many of the closings we would like to do. The decreasing number of transactions at many of these offices makes them highly unprofitable, but moving to an automated model brings its own issues.”

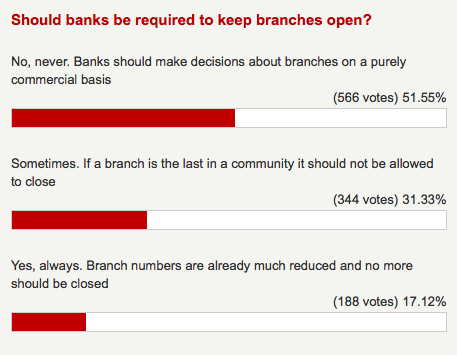

The perceived obligation to keep branches open, and the real estate related costs of closing branches, may explain the rather conservative rate of branch closures to date despite branch transaction volumes that continue to plummet and costs that continue to rise. The same challenge is being faced by banks worldwide, evidenced by a recent U.K. article in The Telegraph asking, ‘Do Banks Have a Duty to Keep Branches Open?‘ Interestingly, more than half the people who responded did not believe banks should be required to keep unprofitable branches open.

Closing Branches in Lower Income Areas

The Community Reinvestment Act, signed into law in 1977, was an effort to combat discrimination and encourage banks to serve local communities. The CRA also required financial institutions to notify federal regulators of branch closings. But most industry followers say the CRA provides a great deal of leeway for banks wanting to close offices, and that the impact is usually only felt when a bank wants to make an acquisition of another institution. In addition, the law has not been updated to reflect the impact of online or mobile banking, making it even more difficult to enforce.

“There is ample evidence that banks have disproportionately closed branches in low to moderate income areas, despite the CRA”, stated Steven Reider from Bancography. “There are few cases where CRA impedes closures and in fact, the regulators have no authority to stop a closing, only the ability to downgrade a CRA rating in a subsequent year’s review.”

To this point, analysis from various sources shows that there are still disparities in how closures over the past several years have occurred, with a significantly higher number of closures in low and moderate income areas and a small growth in branch locations in more affluent neighborhoods. But this doesn’t mean that there are not still a significant number of additional branches that should be closed.

Simply walk into any of the mostly oversized inner city branches and you’ll realize that there is a tremendous overcapacity in most branches. The problem is…how to close these offices with the least amount of community impact?

Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

Build a modern credit card strategy that balances profitability and risk, adopts the latest technology and delivers the customization that cardholders demand.

Read More about Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

Accelerate Time-to-Market with Rapid Implementation

Create a sustainable competitive advantage with faster time to market by drastically reducing implementation time.

Read More about Accelerate Time-to-Market with Rapid Implementation

Closing Rural Branches

While a bank branch serves as the public face of banks and provides an important marketing function in high-traffic neighborhoods, bank branches also play an economic and emotional role in smaller markets, where low transaction volumes make the majority of traditional branches unprofitable. “Bank branches are a symbol of economic health and a vibrant community,” says Jennifer Tescher, head of the Center for Financial Services Innovation, a research group that focuses on people without a banking relationship.

According to Joe Sullivan, CEO of Market Insights, “Banks and credit unions need rooftops and businesses to make the economics of the ‘traditional” branch model work, and unfortunately, this makes some of the smaller towns unable to profitably support large (or many) bank branches. Therefore, you will continue to see a decrease in traditional branch formats in small towns, especially with populations under 10,000 people.”

Adding to the difficulty of closing a branch in a rural market is the fact that the next closest branch may be dozens miles away and the availability of high speed internet and even a strong mobile signal may negatively impact the conversion to online and mobile banking alternatives. Finally, selling an existing bank branch is also more difficult in a rural market, where the commercial real estate market may already be depressed.

Cost of Closing Branches

As mentioned, despite the estimate that as many as 25 to 30 percent of branches are unprofitable, many banks are holding on to branches because of expensive, long-term leases or because past renovations have not been fully depreciated. In addition, it is estimated that the cost of closing a branch is as much as $500,000.

“The biggest barrier to closure we see is not CRA or community pressure; it’s the unwillingness to take the fixed asset write down that the bank would incur when trying to dispose of the facility. Charge against current period earnings = unhappy shareholders.” stated Reider from Bancography.

Kevin Travis, managing director at Novantas in an interview with the American Banker, agreed saying, “Many banks are waiting for the interest rate curve to turn, thinking they will become more profitable and can take the charges when margins are rising. But the flip side is that interest rate relief from widening spreads will lessen the financial pressure to cut costs. And hope is not a strategy.”

Branch Configuration Will Continue to Evolve

While branches will not soon vanish as a transaction and business channel, they will definitely continue to evolve. “Branch closures might slow down or speed up, but as mobile technology continues to become more available, we expect the need to use branches to conduct routine transactions to decrease,” says Tahir Ali, research analyst for SNL Financial.

Ali believes the branch will continue to evolve into spaces used more as marketing centers or consultation spaces. “There will always be transactions people want to conduct face to face,” Ali said, either because of their complications or because they need an immediate result. He also noted that many people still feel more comfortable discussing loan options and filling out loan applications in person than they might at a kiosk or over the phone.

Rather than providing a full-service experience, branches of the future will probably be much more self-service, with automated devices provided as a compliment/supplement to customers’ current mobile and online banking experiences. Banks will offer self-service kiosks where customers can conduct basic transactions, learn about and apply for products, and even meet with specialists via video connections.

An example of this transformation is best illustrated by PNC, where branch closures and significant modifications of branches was discussed as part of the bank’s most recent analyst call. PNC Chief Executive William Demchak told investors that the bank will close branches and turn as many as two-thirds of his 2,700 company’s branches into smaller, more automated locations within the next five years. “We’ll drop the operating costs out of it, and it will deliver a service that tomorrow’s bank client expects,” Demchak said.

“Banks and credit unions need to implement creative strategies that enable their institution to remain economically viable”, said Serge Milman, principal consultant for SFO Consultants. “CRA requirements can be met through efforts other than physical branches…such as with ‘branches on wheels’ or with a ‘pop-up branch’ like has been done by PNC. Fundamentally, the vast majority of consumers do not need / want services delivered in and by a traditional branch. Maintaining such infrastructure is a dis-service to customers (as it raises overall costs for various services), and a breach of fiduciary duty to the Bank’s shareholders.”

Post Office Banking Alternative

Making news recently, the Post Office could serve as an alternative to traditional banks, especially in lower income and rural areas. While a bit of a stretch for many inside and outside the industry, it would not be the first time this has been done in the U.S. Beginning in 1911 and lasting several decades, as many as 4 million people had postal savings accounts with the USPS. In addition, the model would be similar to one used overseas still today.

One advantage would be that the overhead costs would be covered since the USPS already has 35,000 offices, branches, and other locations across the country, with almost 60 percent of post offices are in Zip Codes that have one or zero bank branches. In addition, the agency already handles monetary transactions.

Beyond serving the underbanked/unbanked/debanked, the agency could fill the gap when bank branches need to close either providing basic services themselves or potentially partnering with banks. Not intended to provide loans or business services, current proposals include the possibility of the USPS offering basic banking services such as bill paying, check cashing and making small loans.

There is no doubt that there will be a great deal more discussion around the pros and cons of this idea, but it could alleviate a great deal of the pressure banks are feeling around closing or shrinking unprofitable branches.

The Future of Branches

Rather than being the hub of all banking, branches are destined to become the alternate channel for customers to conduct their banking, integrating with both mobile and online banking experiences. Personalized service will be provided in a different manner, leveraging digital technology to drive a better shopping and buying experience.

Moving to this model will not be easy and will require customer engagement. Hurdles that now exist to closing branches will need to be addressed since the negative financial impact to not closing underperforming branches is significant. “It is broadly recognized now that it isn’t the 1990s anymore and that things need to change,” says Bob Meara, senior banking analyst at consulting firm Celent. “The competitive advantage of having branch density is a huge cost disadvantage.”

Dave Martin, Executive Vice President and Chief Development Officer with Financial Supermarkets, Inc. (FSI) says, “The truth of the matter is that the banking industry does not need the amount of space it currently has anymore. Downsizing traditional branches, trimming networks and testing newer, smaller “alternative” locations is going to happen. The banks who find the most efficient ways for their people to still have face to face contact with customers will be at an advantage.”

He continues, “I don’t think the argument is really ‘if’, but ‘when’. That said, this industry isn’t exactly known for speedy transformation. It’s probably easier to predict what things will look like in 10 years than in 2 years.”

I believe the rate of closures is due to accelerate in the near term. The foundation for these closures has begun, as many banks discussed both closings and branch reconfigurations as part of their recent earnings calls. The challenge, as with many changes in other industries, will be how we can ‘sell’ it to the public at large.