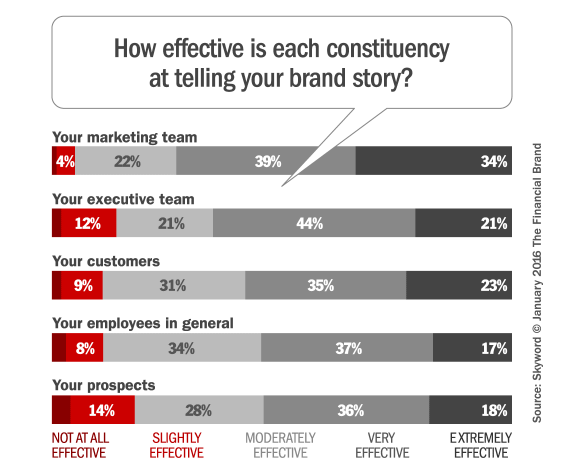

Skyword surveyed 190 marketers and asked them how effective their marketing team (as well as their executive team, employees, customers, and prospects) is at telling their companies’ brand stories.

Three-quarters of them think that they’re doing an “extremely” or “very” effective job, and about two-thirds put the effectiveness of their executive teams in those two categories.

Surprisingly, a larger percentage of marketers think that their customers are more effective at telling the brand story than employees of the firm. In fact, marketers think that their prospects are as effective at telling the brand story as employees are.

My take: Marketers might just be the most delusional people on the planet. And I can’t imagine that, if bank (and credit union) marketers were asked the same questions, the percentages would be anywhere close to the ones that Skyword found in its survey.

Let’s look at these results by each perspective:

1) Marketing. How do the marketers surveyed know that they’re “extremely” or even “very” effective at telling their brand story? In other words, how are they gauging “effectiveness”? It doesn’t even matter — I bet if you asked the members of their marketing team what the brand’s story is, you wouldn’t get a consistent answer.

2) Executive team. A good percentage — no wait, that’s the wrong word, because it’s not a “good” percentage, it’s a “scarily high” percentage — of senior bank execs that I know roll their eyes when the topic of discussion is their bank’s “brand.” Too touchy-feely, too squishy, and too “marketingese” for them.

Then, of course, you’ll get the marketers and execs who’ll tell you that their FI’s brand story is “their superior customer service, and how they go the extra step for their customers/members.” I’m usually numb with mental pain before they even finish that sentence.

3) Employees. A little more than half of marketers think the employees at their companies are effective at telling the brand story. How in the world would the marketers surveyed know whether or not their colleagues from other departments (who, let’s face it, they never interact with) effectively tell the brand story? [I hope I don’t have to actually answer that question for you]

4) Customers. Nearly six in 10 marketers think their customers effectively tell the brand story. Maybe those respondents work for Apple. But for the majority of products and services that consumers buy, we simply don’t give a hoot about that product or service to care about, let alone think about, the “brand story.”

5) Prospects. Many branding experts emphasize the importance of the so-called “customer experience” as a factor influencing a brand’s… uh… brand, or story. If that’s true, then how can prospects who have never interacted with a brand, or experienced the “story” know what the story is, let along effectively tell it? Yet, more than half of marketers think prospects are effective at telling their story. No way.

Instant Messaging. Instant Impact.

Connect with your customers and provide lightning-fast support as effortlessly as texting friends. Two-way SMS text messaging is no longer optional.

Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Vericast’s 2024 Financial TrendWatch explores seven of today’s most critical financial services trends to provide a complete view of the current loyalty landscape.

Read More about Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

There’s a bigger problem here than the delusions marketers harbor about how effectively they tell their brand’s story. That problem is a fundamental misunderstanding of whose story it is.

Seth Godin once wrote “marketing is the story marketers tell to consumers.” He was wrong. Marketing is figuring out which stories you want customers to tell [to] themselves. Stories that come from their personal experience and that strengthen their loyalty to the company, product, or brand. A story that a customer tells to herself — even subconsciously — is the most important factor driving customer satisfaction and loyalty.

A while back, Citi Card ran an ad campaign that focused on customers’ “stories.” In one, a 20-something tells her story:

“I don’t cook. So I made my eat-in-kitchen a fabulous walk-in closet. Since I enjoy a day of shopping far more than cooking, I decided to do a bit of home remodeling. With my Citi card in hand, I set out to get some closet organizers. I bought a shoe rack for the oven, sweater boxes for the cupboards, and 12-inch baskets for handbags up above.”

The ad’s tagline was “whatever your story is, your Citi card can help you write it.” A Citi exec was quoted as saying “Our hope is to get into the heart of the Citi cardholder’s head and make an emotional connection… we want people to select the Citi card because, in so doing, we can help them live a piece of their dream.”

Gag me.

Contrast the Citi customer story with these stories from customers who consider themselves loyal to their banks:

“My partner and I had been trying to adopt a child for some time, when we received word from the adoption agency that a child was available for adoption — in China. But we needed a short term loan in order to make the trip. My bank bent over backwards to approve the loan and get us the money in 24 hours. For that, I will never leave them.”

“My ex-wife and I were going through a divorce and I called one of our financial providers to cancel a credit card and insurance policy we had with them. The rep on the phone said ‘I hope I’m not overstepping my boundaries, but if you’re going through a divorce, we have a whole department that can help with all the financial arrangements you need to make.’ To make a long story short, we were able to transition our accounts easily. For making it such a painless process, for being there when I needed them, and for figuring out that I needed help in the first place, I’ll never do business with another financial firm.”

Notice anything different in the stories I’ve related and the one Citi told in its ad? There are three important differences:

1. An element of the unique. What exactly is so special about having the Citi card in this example? Answer: Nothing. In the story that Ms. WalkInCloset tells, you could pretty much tell that story substituting a Capital One, Amex, Discover, or any other credit card. But not every financial firm could have done what the firms in the other two stories did. For a story to become a “story that a loyal customer tells” it needs to be something that not just any bank can do.

2. An element of the unexpected. A woman goes into a store, buys a shoe rack, uses her credit card to pay for it. Nothing out of the ordinary about that story. But getting approved for a loan — and getting the money — in 24 hours? Or having a call center rep figure out that there’s something deeper than just closing out a couple of accounts? You don’t expect that to happen. And it’s the unexpected that drives the most important customer stories.

3. An element of the emotional. While it might be important to Ms. WalkInCloset that she is redoing her kitchen, buying a shoe rack or a sweater box doesn’t quite rise to the level of emotional content that needing money to travel to China to adopt a child, or getting through the stress of a divorce does. It takes an emotional situation to develop an emotional bond (this doesn’t have to be a negative, or stressful situation — positive ones work well too).

It scares me that there are so many marketers roaming around the business jungle thinking that they’re effectively telling their brand’s story, when: 1) they have no means for measuring that effectiveness; 2) no clue what their brand’s story is; and 3) no understanding that it’s their customers’ stories that matter the most.