The report: Assessing the Implications of a Productivity Miracle [November 2023]

Source: Bridgewater Associates

Why we picked it: The generative AI explosion is reverberating into 2024, with industry leaders looking to understand its long-term implications for cost structure and margin improvement. As generative AI becomes increasingly able to handle the sort of task typically done by white-collar workers, banking leaders must understand the opportunities and threats it poses.

The report offers an overview of AI’s potential impact on productivity in the coming decades, with predictions that can be extensible to the banking sector.

Executive Summary

While most cognitive tasks cannot yet be done with AI alone, Bridgewater believes AI could soon outperform knowledge economy professionals. This is a critical issue for the banking industry, which relies heavily on cognitive labor performed by a white-collar workforce.

The report explains that during the information technology revolution of the 1990s, an industry’s ability to wield pricing power in its markets was a major factor in determining whether it would benefit from, or fall prey to, a new technology. Bridgewater also notes that AI could drive shifts in economic activity that render some industries obsolete and give rise to other, entirely new ones.

That would set the stage for upheaval in banking and financial services as the fortunes of business customers can shift dramatically, as happened, for example, in the internet’s early waves of transformation.

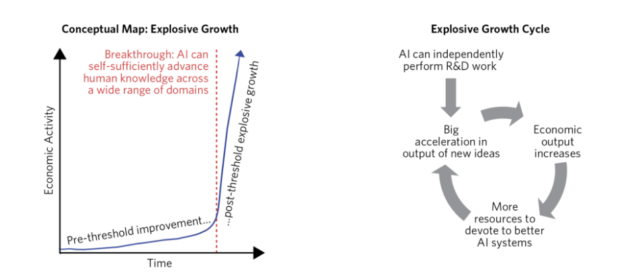

Finally, the report describes an extreme scenario in which AI becomes capable of “automat[ing] the advancement of human knowledge itself,” which could lead to “explosive growth” in which productivity expands at an unprecedented rate.

Read more about recent research from Accenture with a different take.

Key Takeaways:

- AI has the potential to drop the marginal cost of cognitive tasks to zero.

- The capacity of industries to continue charging consumers even as production costs plummet — which Bridgewater describes as “pricing power” — was a critical factor in determining which industries benefited from the IT revolution. (E.g., software companies benefited hugely while newspapers and camera companies suffered.)

- AI could generate a flow of free products and services such as investment advice or retirement planning for consumers, which would free up income for other expenditures — assuming the provider has pricing power to leverage.

- An extreme and unlikely scenario, in which machines can learn and build with more independence, would allow for the automation of innovation itself, is considered.

What we liked: The report offers a concise yet big-picture view of the potential long-term impact of AI with important historical context to help explain the characteristics of industries likely to win or lose.

What we didn’t: The report at times feels overly abstract because it does not identify which industries or sectors would be most affected by the marginal cost of cognitive tasks falling to zero. The “explosive growth” scenario is so far down the road that it seems more speculative than analytical.

The unfair advantage for financial brands.

Offering aggressive financial marketing strategies custom-built for leaders looking to redefine industry norms and establish market dominance.

Success Story — Driving Efficiency and Increasing Member Value

Discover how State Employees Credit Union maximized process efficiency, increased loan volumes, and enhanced member value by moving its indirect lending operations in-house with Origence.

Read More about Success Story — Driving Efficiency and Increasing Member Value

Things that made us go “hmmm”: The report describes the extreme scenario of zero-cost innovation as having potential to generate massive economic growth but doesn’t explore its impact on the human workforce. The obsolescence of human innovation is for many people a doomsday scenario that could fuel unemployment (and is in fact a contingency regulators are preparing for). Couching this exclusively in economic-growth terms seemed to ignore the elephant in the room: the massive societal shift that would, in itself, create potentially unprecedented volatility and risk for most institutions, banking included.

The Economics of AI

How will the economic impact of AI be different from that of previous technological shifts? It could look the same, argues Bridgewater. “There’s a lot we can learn from past cases—the economics of durable margins have not changed, even as their technological basis has shifted.”

In the banking industry, AI could replace huge numbers of white-collar workers ranging from loan officers and risk analysts to compliance experts and technology specialists — adding to the existing trend of chatbots replacing customer service representatives. This could drive down the cost to the consumer of services such as estate planning — perhaps to zero.

The key factor – pricing power: The report looks at how pricing power could help industries reap the benefits of AI. Companies that can provide goods and services at low marginal cost because they have already made large up-front investments enjoy barriers to entry that make it difficult for competitors to enter the market even as an enabling technology becomes widely available.

To be sure, providers of large language models benefit from exactly that advantage (due to the high cost of training their models). But downstream players can also gain pricing power by differentiating their products on the AI platform — especially those with access to high-quality proprietary data that sets them apart from their competitors.

Pricing power in the banking industry has long been a matter for debate: Many banking services are already considered to be commoditized but an institution’s size and its mix of off-balance sheet offerings can tip the scales in the other direction. AI would likely amplify these conditions: Institutions with substantial, well-managed data sets — i.e., larger and more sophisticated players — would benefit most.

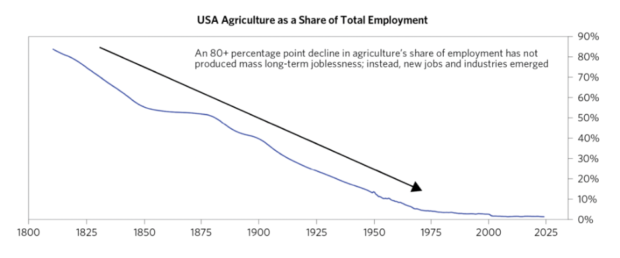

Employment shifts to new sectors: The report notes that agriculture constituted 85% of employment in the U.S. in the 19th century and now makes up just 1.4%. Those workers moved to new sectors that emerged as a result of automation, such that most agricultural jobs that exist today did not exist 50 years ago.

Displacement of white-collar workers by AI could have a similar effect. Bridgewater describes this as a “reshuffling of spending and activity,” without predicting where new workers would land.

- How to Get Banks, and Regulators, to Embrace AI for Investment

- 5 Ways Automation Moves Financial Institutions Forward, Faster

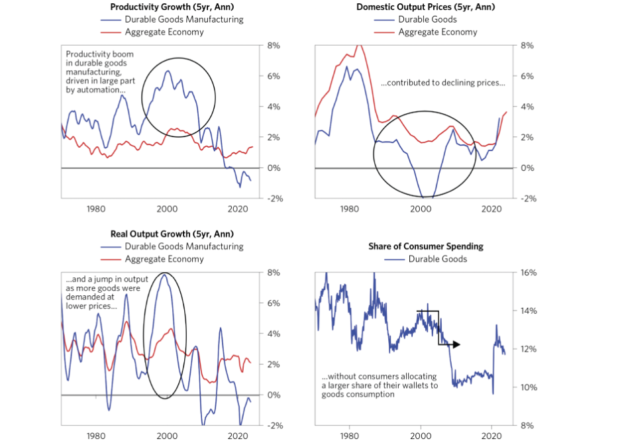

New spending power: AI could create a host of free services such as custom software development and tailored legal advice – which in turn free up resources for consumers to spend on other goods and services. Bridgewater notes that the automation of durable goods manufacturing in the 1990s and 2000s led to greater consumption of those same goods as they became cheaper. At the same time, consumers boosted spending on discretionary services (the report does not say which ones).

AI could similarly spur consumption of low-cost cognitive services while also driving spending towards new industries that do not yet exist. The report’s use of the digital photography example might also be useful for bank leaders as they consider AI’s implications for business lending. Digital photography of course created a need for storage, and the current explosion of data centers; so who benefits from the AI transition?

For instance, there are already a host of so-called “AI orchestration startups,” providing services to help organizations deploy AI, which are predicted to create a wave of new unicorns.

What if AI makes innovation free? Bridgewater posits this as an extreme but unlikely scenario in which artificial intelligence alone can take over innovation that has until now depended on large, well-educated workforces. “Whereas prior innovations automated specific tasks or assisted human efforts to distribute and advance knowledge, a very sophisticated AI could automate the advancement of human knowledge itself.”

This would require huge advances in what is now the largely theoretical field of artificial general intelligence, or AGI, that seeks to create software that can teach itself to complete tasks it was not trained for. Widespread adaptation of AGI could lead to an exponential increase in the rate of innovation as economic productivity gains allow for even more resources to be invested in new innovation-generating AI.

Bridgewater points to very real constraints that make the explosive growth scenario unlikely, including the possibility that development of new hardware and sourcing of raw materials could slow AI deployment. But it adds that “assigning it even a tiny probability would dramatically alter our average expectations for what the world will look like decades from now.”