Just as interchange income was devastated in the months after the pandemic hit, overdraft fees earned by banks and credit unions also dropped precipitously. One reason was that the massive government stimulus payments, along with unemployment insurance extensions, helped consumers avoid overdrawing their checking accounts. Various forbearance programs were another factor, as was the easing of overdraft terms and outright waivers by numerous financial institutions for varying periods of time.

Even though overdraft fees in the fourth quarter of 2020 soared by 64%, the median decline in overdraft revenue for the banking industry was 22% for all of 2020, according to S&P Global.

Will this key revenue source — vilified for years by nearly every consumer interest group and many politicians — return to its pre-COVID levels? Or will more financial institutions follow the lead of U.S. Bancorp and Bank of America in rolling out low-cost, small dollar loan options intended as an alternative to overdrafting and payday loans?

Perhaps more importantly, has the pandemic-fueled growth of neobanks like Chime, Varo, MoneyLion and Dave created a new paradigm for transaction accounts with their more liberal overdraft policies?

For answers to these and other questions, The Financial Brand reviewed available research and spoke with a preeminent authority on the subject of overdrafts and transaction accounts, economist Michael Moebs. As CEO of Moebs Services, Moebs has conducted research on overdraft charges since 1986, testifying before Congress on the politically charged subject several times.

Moebs’ most recent survey of 3,126 banks, credit unions and savings banks, conducted in November 2020 uncovered that community banks and larger credit unions are leading the way toward lower overdraft prices.

But Moebs also raised several warning flags for incumbent institutions during the interview.

Industry Cloud for Banking from PwC

See how PwC's Industry Cloud for Banking can help solve everyday business challenges.

Creating A Community with CQRC’s Branch Redesign

Find out how SLD helped CQRC Bank to create the perfect harmony of financial services, local culture, and the human touch in their branch transformation.

Read More about Creating A Community with CQRC’s Branch Redesign

New Data on OD Prices Shows Diverging Trends

In his most recent research on overdraft pricing, Moebs discovered that the average overdraft price for the largest financial institutions (banks and credit unions) was the highest ever at $33.19, up more than a dollar from the previous high. There was a notable difference, however, between the largest banks, where the average price was $34.33 and the largest credit unions, where the average was $26.18.

Key Finding:

Small community banks are displacing small credit unions as having the lowest average overdraft price, at $26.26 versus $28.40 per overdraft, according to Moebs Services.

Even though the largest credit unions are moving their overdraft pricing lower, Moebs says higher operating costs limit the ability of small credit unions — which used to have the lowest prices — to lower their prices further.

Other highlights from the Moebs Services November survey:

- The highest price by region is the East (Maine through New Jersey) where overdrafts average $31.29 per overdraft.

- The lowest regional price is in the West (mountain states and the West Coast) at $29.18.

- Kansas has the lowest average state price at $28.55.

- Maryland and Florida share the highest average fee at $33.13.

- The smallest average fee of major cities is San Diego at $27.42, while the highest is $34.90 in Miami.

Shifting Political Winds Could Quash OD Fees

The thinking among many in banking is that the Biden administration will see a return to a much more activist Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and possibly the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency as well. The agencies are expected to focus in particular on fair access to credit and unfair fees, according to Novantas. As their analysts put it, “The CFPB nominee, Rohit Chopra, is at the core of the two priorities. With his extensive background in consumer protection within banking, the CFPB is likely to push for credit policy reform, more progressive lending criteria and an overhaul of overdraft fees.”

( Read More: Biden’s Banking Watchdogs Could Create Headaches for the Industry )

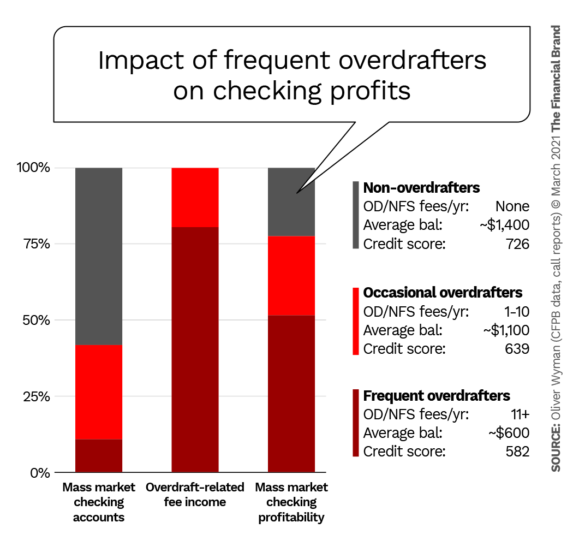

CFPB did a major study of frequent overdraft users in 2017 and its findings continue to fuel the desire of politicians and consumer activists to restrict OD fees. The study found that most overdraft-related fees are generated by a small subset of consumers “frequent overdrafters”), who overdraw their accounts once or more each month, as Oliver Wyman states in its report, “Beyond Overdraft“.

“These frequent overdrafters represent only about 10% of mass market consumers but generate more than 80% of all overdraft- related fee income,” Oliver Wyman states. It adds that “frequent overdrafters effectively ‘pay for’ the 60% of mass market checking customers who do not generate enough in interest income or fees to cover their fully loaded cost.”

The Oliver Wyman report cites four categories of frequent overdrafters. As excerpted below, their particular circumstances suggest possible product responses for banks and credit unions:

Consistent overdrafters. Have little variation in income or expenses month to month, but have chronically low balances. They tend to overdraft nearly every month, often unintentionally, suggesting a need for better spending management and tracking tools.

Frequent debit swipers. These heavy users of debit cards have relatively high incomes ($7,800 in deposits per month) “but compromised credit and episodic cash shortfalls that result in multiple overdrafts.” Better tools for coordinating spending and more formal lines of credit to cover expense/income mismatches could help this group.

Volatile cashflow overdrafters. Gig workers typify these consumers, who often have big swings in income and expenses. An affordable small dollar credit or an emergency savings cushion could help them the most.

Young and unestablished overdrafters. As might be expected, Gen Zers and younger Millennials (people in their 20s or early 30s), have low balances, more volatile income and expenses, and no established credit.

Read More: Rethinking Checking Account Strategy in a Digital Banking World

Moving from ‘Penalty’ to ‘Mistake’ (and Charging Less)

The CFPB report’s conclusion that many more overdrafts result from consumer inattention or timing errors than from a financial emergency is a point Mike Moebs has been making for years. He believes the industry overall is gradually moving away from the notion that “You shouldn’t do this,” and the resulting stiff penalty fees. Obviously, the pricing cited above indicates that the largest banks haven’t joined the parade yet, although four out of five of them do offer a “no overdraft” basic checking option, which reports indicate have proved popular.

Moebs has long advocated that “Since overdrafts often are the result of an error, why charge $30 apiece for them. Instead charge $20 or less.”

Despite the heightened political focus on fees and other financial fairness issues, Moebs doesn’t see overdrafts, nor the revenue they generate, going away, but it will increasingly take a different form.

In fact, in some ways it already has.

Currently, between 30% and 35% of American consumers — about 120 million people — overdraw their primary transaction account, according to Moebs. All told that led to overdraft revenue of $31 billion in 2020, down $6.6 billion from its peak of $37.6 billion. (That figure includes the fees for the overdraft itself, an NSF fee, and fees for stop payment, the return of the deposited item, plus the transfer from a deposit account or a line of credit.)

Did You Know?

Payday lenders, far from dead, now ‘own’ more than half of overdraft market.

A startling statistic Moebs shared with The Financial Brand is that payday lenders now have the biggest share of the overdraft market. It’s grown from between 5% and 10% in 2000 to 54% now. Payday lenders are active and profitable in 34 states, according to Moebs. More significantly, on the internet, payday lenders from the U.K., Korea, Australia and New Zealand in particular are extremely aggressive.

They are overdraft competitors because they offer consumers that are in a money bind a less-expensive option, Moebs explains. For less than $20 typically, a person gets a loan, which they then deposit in a financial institution, and have 15 days to pay it off. That’s considerably less than the $30 fee and an average of nine days for payback that an overdraft at a large bank would cost them.

Read More: How Financial Marketers Can Punch Back at ‘Consumer-Friendly’ Neobanks

But the Biggest Overdraft Competitors Are Fintechs

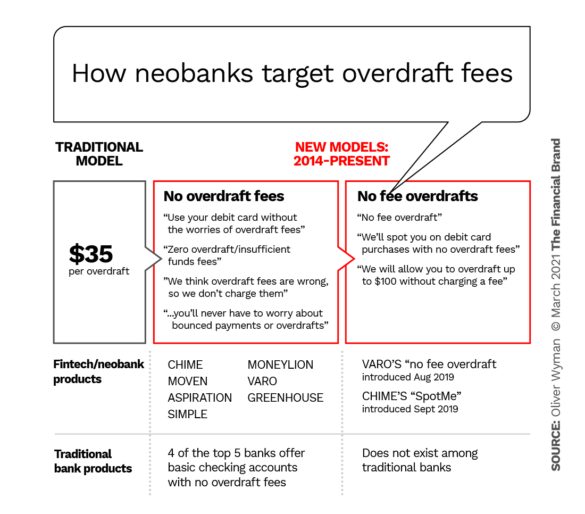

An even bigger challenge to the revenue stream banks and credit unions get from overdrafts and related fees is what the fintechs and neobanks are doing.

In its overdraft report, Oliver Wyman used ill-fated Blockbuster as a warning to financial institutions.

“In 2000, late fees accounted for 16% of Blockbuster’s annual revenues,” the report states. “While these fees represented their customers’ number one complaint, the company was slow to address the problem.” Until it was too late.

The firm believes a parallel may already be happening in retail banking. As it notes, “all of the prominent digital-only banks currently feature accounts that do not charge overdraft fees. Collectively they have attracted millions of new accounts.” Features vary by the company and some do charge a fee after a certain period of time.

“The fintechs mount the greatest overdraft challenge,” Moebs agrees.

Incumbent financial institutions are already reacting to this threat in several ways. One is to offer short-term, low-cost loans, as Bank of America is doing for a $5 fee. Another is to offer no-bounce checking accounts, or to match some of the features offered by the neobanks, such as not charging a fee if an overdraft is under a certain dollar threshold, or offering a 24-hour grace period during which a customer can bring an account back into balance.

Or, as Moebs recommends, lower the price to less than $20 per overdraft and raise the limit. The average industry overdraft limit remains where it’s been for years — $500. That’s the amount a consumer can overdraft up to. Moebs urges banks and credit unions to raise the limit to a minimum of $1,500 and lower the price below $20 and “consumers will love you.” It reduces their cost and gives them more of a cushion should they make a mistake, he explains. Ultimately the bottom line impact will be nil, Moebs maintains, because people will overdraft more as a result.

A key requirement needs to this change, however: Traditional institutions must be more transparent about their overdraft pricing. Moebs says that the industry is moving in this direction. Of the 10,300 depository institutions he tracks, a little over 40% report overdraft limits and pricing details on their website. That’s up from about 10% in 2007.