Banks continue to close branches and shrink the size of their networks continues, but institutions with over $10 billion in assets are responsible for the vast majority of these closings.

“The smallest U.S. banks are still pruning their branch networks, but larger banks are taking out the chainsaw,” says a pair of experts from SNL Financial, who has tracked the size of bank branch networks for at least the past decade.

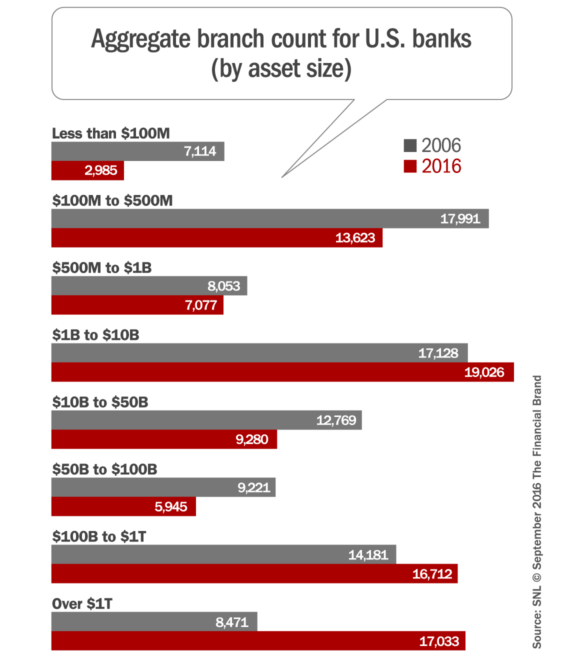

Over the last 10 years, SNL says the U.S. banking industry as a whole has cut 3,012 branches, but those institutions with less than $1 billion in assets have actually opened 3,275 net new branches.

Banks with assets over $1 billion now control almost three-quarters of all active branches, despite closing more than 6,000 branches over the last decade.

SNL says the total number of branches operated by the very smallest banks — those with under $100 million in assets — have fallen from 7,114 in 2006 to 2,985 branches in 2016. (Of course, many financial institutions with less than $100 million in assets that have only one branch, and closing it would mean they were out of business.)

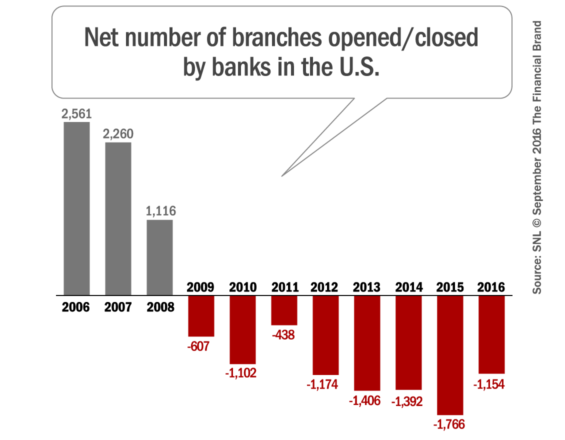

Many pundits and banking industry observers have decried branch networks as “dead” and irrelevant, but the overall pace of closings doesn’t seem to be gaining steam. In fact, the number of branches closed annually has held fairly steady since about 2010 — between 1,000 and 1,750 branches closed per year.

After seeing 1,766 branches closed in 2015 — an all-time record in the U.S. — there have only been 1,154 branches closed through the first nine months of 2016. Is the trend reversing?

Read More: Will Bank Branches Ever Die?

The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Learn how to enhance your brand’s local visibility, generate more leads, and attract more customers, all while adhering to industry regulations and compliance.

Read More about The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Join industry’s leading AI conference - free passes available!

Ai4 is coming to Las Vegas, August 12-14 2024. Join thousands of executives and technology innovators at the epicenter of the AI community.

Read More about Join industry’s leading AI conference - free passes available!

There is no shortage of banking consultants who say the branch closing trend is purely a reaction to the rise of digital channels — namely mobile. The common argument goes something like this: “Consumers don’t need a branch anymore because they can bank online anywhere, anytime, so banks should be shuttering their brick and mortar locations.”

The surge in digital banking channels is definitely a factor. In 2013, Accenture found that 48% of Americans surveyed said they would switch banks if their current provider’s local branch closed. In 2015, that share shrank to just 19%. But taking this singular view grossly oversimplifies the complex calculus involved with any assessment of branch networks.

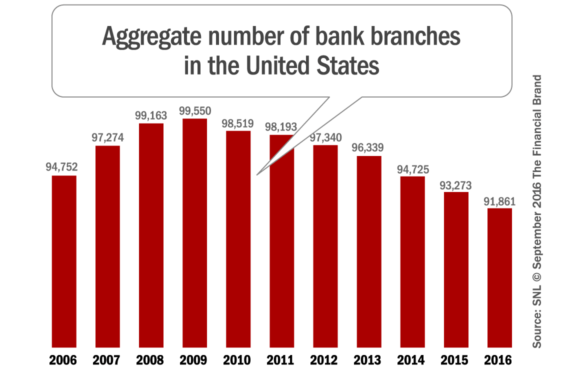

For starters, it ignores how severely over-branched the banking industry had become. During those heady days that inflated the subprime bubble, banks couldn’t open branches fast enough. Over a three year span from 2006 to 2008, nearly 6,000 new branches were opened.

Once the bubble burst though, the branch opening spree came to a screeching halt. And then in the wake of the global economic meltdown (that banks helped create), there was a mad scramble to pare losses, cut costs and raise capital. Branches were an easy target, and it wasn’t hard to .

You could essentially argue that the banking industry has simply closed branch locations that probably should have never been opened in the first place — that the banking industry flooded the market, and it’s simply taken them the a decade to unwind a problem it basically brought on itself. In light of all the digital and mobile developments, it’s surprising that a lot more branches haven’t been closed.

Consolidation in the industry is another factor driving branch closures. The technological hurdles banks face have driven many to merge. And thanks to the mountain of new regulations and compliance issues that resulted from the financial crisis, financial institutions have pursued greater efficiencies through scale. Between the size of the technology investment most still need to make and the increased regulatory burden, U.S. banks have seemed to conclude that “bigger is better.”

First Midwest Bank is one such example of this trend. In mid 2016, First Midwest, which has about 110 branches, announced its acquisition of Standard Bank, along with their network of 35 branches. The deal will result in the closing of 16 branches, which the bank says will be mostly due to overlap.

Going forward, the impact of digital- and mobile banking channels will certainly continue be one of the forces driving branch closures. In September 2016, Fifth Third Bank said it would shed 44 branches as part of an ongoing assessment of its retail banking network. That’s on top of more than 100 locations Fifth Third has already closed. The bank cited “changing customer preferences” toward increased digital transactions as the reason. By early 2017, Fifth Third’s branch network will be 12% smaller than it was in 2015.

“We are very mindful that branches are important. We are looking at the type of branches, the location of those branches and doing what’s right for our shareholders and our customers. But I would expect this to be an annual exercise,” said Fifth Third CEO Greg Carmichael.

The trend isn’t isolated to the U.S. either. Westpac Bank in New Zealand has announced it will be pruning 19 branches from its network.