Human trafficking — a blight on mankind throughout recorded history, and beyond — unfortunately is still thriving in the 21st century. In all its various manifestations human trafficking generates an estimated $150 billion in illicit profits annually, according to Polaris, a nonprofit group previously known as the Polaris Project.

Because of its essential role in facilitating the movement of money, the banking industry has long been a key to preventing human trafficking transactions. And while the three experts The Financial Brand spoke with agree the industry has made strides in this important work, it still has much to do to keep up with the perpetrators.

“One thing I want to make sure the industry understands is that human trafficking is very much evolving all the time in response to the external environment,” says Sara Crowe, Strategic Initiatives Director of Financial Systems at Polaris. Even though she believes banks and credit unions have done a good job so far, she warns against leaders thinking “Okay, we did that, we’re done.

“We’re not going to be done,” Crowe states. “This isn’t a short-term project, this is ongoing.”

Don't Back Off:

Banking has made great efforts to help reduce human trafficking, but new challenges keep cropping up.

For instance, instead of relying solely on cash solutions to launder money, human traffickers are now using cryptocurrencies, points out Chris Caruana, Team and Product Strategy Head at technology company Feedzai.

The criminals are now building their money needs around the movement on a blockchain, Caruana tells The Financial Brand, adding that financial institutions are struggling with the complexity of cash to crypto and vice versa.

It takes putting oneself in the shoes of the criminals, Caruana points out. Imagine you have $10 million in dirty money, how are you going to avoid the banks and regulators?

“As you start to think about these processes, you find gaps and weaknesses within the existing system. That’s where banks have to go and close the gaps — it’s that whole risk assessment piece,” he notes.

Read More: Banks’ Brand Risk Grows As People Become Numb to Cyber Fraud

Industry Cloud for Banking from PwC

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking applies our deep industry knowledge to your specific business needs

Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

83% of FI leaders agree investing in AI is essential for 2024 but how you leverage AI is instrumental in success and meeting customer expectations.

Read More about Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

How Human Smuggling and Trafficking Work

The practice of human trafficking may have existed as long as humans have, but how the perpetrators operate, including how they move money and launder the profits continually changes, which in turn creates a more consequential duty for banks and credit unions. John Byrne, Executive Vice President and Chairman of the Advisory Board at AML Rightsource, points out that institutions have approached him to discuss the different situations they are encountering, such as how many of these transactions take place at massage parlors or nail salons.

“They say ‘we’re noticing a lot of activity that we think is unusual, but it doesn’t fit into traditional buckets’. It’s not fraud, it’s not money laundering, but it could be indicators of trafficking,” Byrne explains. He says that this nuance can make it difficult for institutions to identify potential human trafficking situations.

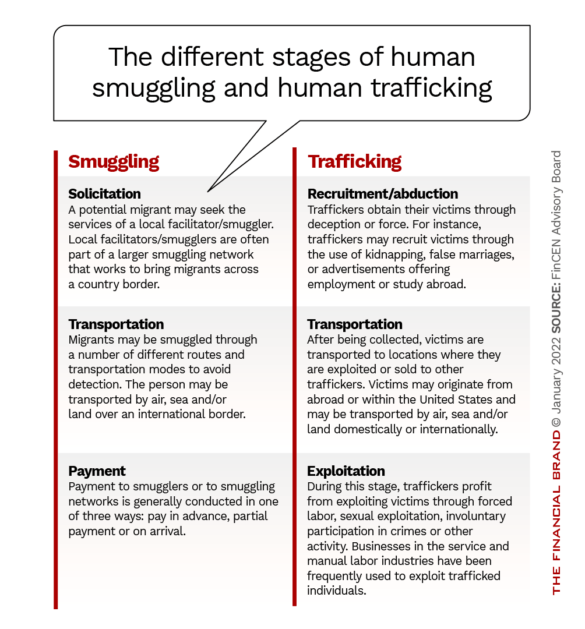

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) released a report several years ago detailing the differences between smuggling and trafficking, the different stages and what banks and credit unions can — and should — do to prevent it from happening. To understand the complexities of today’s human trafficking environment, it’s crucial that banking first consider the fundamental characteristics of the issue.

First off, there are significant differences between human smuggling and human trafficking, although they are sometimes misconstrued. One example of human smuggling is bringing unauthorized immigrants into the United States.

Human trafficking, on the other hand, involves “recruiting harboring, transporting, providing or obtaining a person for forced labor or commercial sex acts through the use of force, fraud or coercion,” according to the FinCEN report. The agency notes that individuals from economically depressed countries or areas have the highest vulnerability to human trafficking.

Financial institutions come into play, by recognizing the red flags that could indicate human trafficking. Some of the major ones that FinCEN pointed out include:

- Multiple wire transfers, generally below $3,000 sent from all over U.S. to common beneficiaries along the southern border.

- Multiple wire transfers at different branches of one institution on same day/consecutive days.

- Money flows that do not fit common patterns — from a country with a high migrant population to somewhere along U.S. southern border.

- Unusual currency deposits into U.S. financial institutions, followed by wire transfers to countries with high migrant populations.

- Any account that appears to be a funnel account where cash deposits, often not exceeding $10,000 “occur in cities/states where the customer does not reside or conduct business.” Funds are usually withdrawn the same day.

- Checks deposited into these funnel accounts that are pre-signed and/or have different handwritings.

The full list can be found in the original FinCEN report, which also explains that banks and credit unions are more likely to identify these warnings at the ‘exploitation’ stage more than at the abduction or transportation stages. FinCEN also published a supplementary advisory in October 2020.

Anti-money laundering programs and financial crime campaigns are just one piece of the larger puzzle, Crowe states. She believes that FinCEN needs to distribute a more comprehensive update of its human trafficking advisory report. For instance, banking can inadvertently support human trafficking by failing to invest in environmental, social and governance (ESG) initiatives as well as not building out financial access and inclusion programs.

“There is a lot of data showing people who don’t have access to mainstream financial services — particularly access to reputable lenders — are at really high risk of human trafficking,” Crowe maintains. “If you’re a migrant worker trying to move to a different country and there are some costs associated with that, you maybe have to take out a loan from a loan shark.” The debt can then quickly rack up and put these populations in a dangerous position.

Learn More: Why Banking Is Only at the Start of Its Diversity and Inclusion Journey

How to Incorporate Technology to Prevent Trafficking

Many of the indicators referenced above can be caught by technology. “There are all these risk signals that organizations should be looking for,” Caruana says. “They’re not going to be able to look at them manually, you need technology in order to do that.”

Anti-trafficking technology is a key project of the MIT Lincoln Laboratory. Lead researcher Matthew Daggett explains that the technology they are designing tracks signatures of human trafficking events globally. The system looks at three different kinds of data — text, imagery and audio — to compile a persona of potential perpetrators.

Companies like Feedzai are constructing similar technologies just for the banking industry to more accurately trace and identify transactions which could indicate human trafficking. Feedzai works with over 100 financial institutions to date, such as Citi, Lloyds Banking Group and Santander as well as a small network of digital-only banks.

Where The Human Element Is Needed

Technology is obviously key, but not the entire solution. Byrne, for one, believes that banking needs to retain the human intelligence element in its efforts to combat human trafficking, and not replace it entirely with artificial intelligence.

Maybe 25 transactions come through after midnight from one account, he explains, and maybe the technology flags it. From there, it should automatically go to a trained investigator. “Can you create an algorithm that will do that? I’m sure there are ways. But, even when you talk to law enforcement, even the younger folks will say that you still want that manual review with the experts that can take the data and understand it.”

There is a plethora of situations where human intelligence is necessary. Crowe says when the Bakken oil boom in Montana and North and South Dakota was getting underway beginning in 2006, it was imperative that anti-money laundering organizations understood the context of the issue.

“There was a huge influx of people in the oil industry, primarily men, to an area that has previously been very sparsely populated,” she explains. In addition to housing shortages, there was also a lack of adequate law enforcement, which increased the likelihood of sex and labor trafficking.

In situations like these it’s important to have humans looking for potential red flags.

Indicators of human trafficking can be seen in a bank or credit union branch, Byrne points out, which is when training frontline staff is most important.

“Let’s say an individual comes in with two or three women that have their own separate bank accounts, they don’t speak English and this person is speaking on their behalf,” says Byrne, noting this can happen with elder abuse cases as well. “That could be a clear indicator of a trafficker who put funds in their individual accounts so he or she can move the funds more quickly.”

Ready On All Fronts:

Technology is an essential tool to prevent human trafficking — but it is crucial as well to have human eyes and connective intelligence focused on the issue.

Anti-money laundering programs are a great way to start addressing the issue, a step which most financial institutions have already taken. But there are other methods for success as well. For instance, banks and credit unions can receive an anti-trafficking certification, offered by the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (ACAMS), which trains financial institutions and their staff how to best approach human trafficking.

Polaris also jumpstarted its Financial Intelligence Unit in partnership with PayPal, which offers players in the banking industry tools, research and data (from the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline) to help banks and credit unions understand developing threats. Part of this effort is also found on the online platform STAT — Stand Together Against Trafficking. Institutions can collaborate on the platform and learn from one another to help spot trends.

Cryptocurrency is one of those upcoming trends. The three experts The Financial Brand spoke to all acknowledge that crypto could be an impending threat that the AML space will need to deal with. Crowe says there have been two traditional ways crypto has been used for human trafficking, but it could eventually have more impact.

“The first is in exchange for child sexual abuse materials or child pornography,” she explains. “The other place that we have seen it is to pay for online advertising or escort services.” Over time, she expects to see human traffickers using crypto to pay for sex as the payment method becomes more mainstream.

Read More: Banks and Credit Unions Wade Into Crypto Banking (And Why)