We all received the same lecture on the first day of banking school, and it started with the professor writing three large letters on the freshly-cleaned blackboard: C. O. F.

For good reason. Without a sharp eye on cost of funds (COF), banks and credit unions can expose themselves to interest rate risk (among many other pitfalls), with likely detrimental long-term effects. If the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020/21 pandemic have taught us anything, it’s that net interest margins can compress quickly — and stay compressed much longer than anyone expects, or most models predict.

These periods of margin compression revealed how little control we have over our return on earning assets versus market forces. The world has changed and prevailing rate environments are no longer the singular driving force. That said, there remains significant opportunity on the deposit side that will ultimately enable greater control of that critical margin.

Cost of funds will always fall short when assessing the true cost for banks’ and credit unions’ most common deposit products: checking accounts.

To illustrate, a group of qualification-based, high-interest checking accounts at one of our client institutions has a median of $8.57 in monthly interest expense or a COF of 0.81%. That’s high enough to send any chief financial officer running the opposite direction. But those same accounts generate a median of $10.07 in monthly net non-interest income (NII). A complete examination, one that accounts for loans generated or supported by these accounts, reveals that they generate $33.16 every month in median marginal profit per account.

Clearly, basing strategic funding decisions on COF alone is painting an inaccurate picture.

Consider a New Acronym

Cost of funds works well for deposit products like savings accounts, money market accounts, and CDs because there’s little non-interest expense or income in these accounts. As we just saw, the same isn’t true for transaction accounts. COF only accurately accounts for the interest expense associated with those accounts. However, those same accounts also have non-interest expenses and generate non-interest income, which is easily buried in the balance sheet and not properly associated with these deposits.

Consider a free checking account: while it has a 0% cost of funds, there are a number of marginal expenses that must be considered — processing checks, sending statements (especially if they’re paper), core fees — along with whatever club account features or free toasters you may add in an attempt to differentiate. But there are also sources of non-interest income, mostly debit card interchange and overdraft revenue.

When you look at this whole picture — interest expense, non-interest expense, and non-interest revenue — you are now looking beyond COF, and seeing a holistic view of the under-reported (and grossly under-utilized) metric referred to as “cost of deposits” (COD).

The Math of COD:

Cost of deposits = (non-interest income) - (interest expense + non-interest expense)

A lot of revenue and expense flows through non-interest-bearing checking accounts that never impacts the 0% cost of funds. Reliance on COF means many institutions lack visibility into these numbers because most (if not all) of these sources are reported and tracked en masse across the entire deposit suite. This makes it virtually impossible to assign marginal expenses and revenues to individual product types, and can ultimately lead to poor strategic decisions.

Do Better Than Cost of Funds

Transaction accounts are relatively new compared to the long history of banking. Overdraft and interchange revenues are even newer. Accurately measuring these factors into cost of deposits just hasn’t become mainstream.

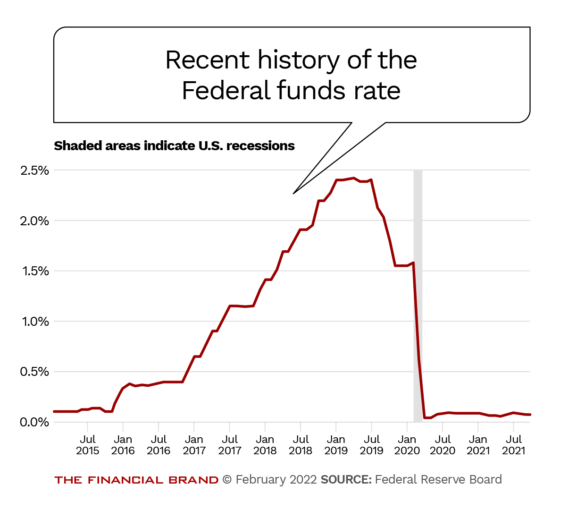

The current Fed funds rate is sitting near the floor, although inflationary pressures may force it to climb. This has left many community financial institutions facing margin compression — even though deposit rates are rock bottom, competition for new (and painfully scarce) loans is putting downward pressure on loan rates as well.

Traditional responses to this type of compression won’t work:

- Increase loan rates — The competitive loan market makes this next to impossible, except for institutions who find ways to compete on something other than rate.

- Decrease deposit rates — Most financial institutions have dropped their deposit rates as low as possible, making this approach infeasible for nearly everyone.

- Decrease non-interest expense — Cost-cutting is likely to handicap growth.

- Increase non-interest revenue — Traditionally, this has meant new and higher fees or other strategies that draw intense consumer ire. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

If we continue looking through COF blinders, the only conclusion is to raise loan rates and hope that your competition quickly follows suit. That’s clearly not a desirable or winning strategy while loan demand remains less than aggressive.

The Hidden Relationship Between Deposits and Loans

There is a path forward that lessens your sensitivity to the prevailing rate and bolsters your balance sheet. Reward checking accounts are currently (in 2021) seeing a COD of -1% (negative cost translates to income). Those same account holders are not only 68% more likely to take out a loan with your institution, they’re also bringing in much more significant loan yields. Let’s say the average loan yield is at or near 5%. That leaves you with a 6% spread or net interest margin, which is twice the 2021 national average and 150 basis points higher than the 1994 peak of 4.9%.

While standard free checking accounts may have their place in some retail portfolios, the fundamental performance of reward checking offers a two-fold benefit: demand deposit accounts that generate profit prior to being loaned back out, and an exceptional margin spread when they do get loaned out.

COD may not appear in the banking textbooks today, or even next year, but it’s clear that relying on COF will cause you to overlook a massive revenue stream that comes with reward checking accounts.