For the 2016 Retail Banking Trends and Predictions article here on The Financial Brand, I contributed this prediction:

“The most significant trend of 2016 will be the ‘platformification’ of banking, where both existing banks and startups begin a strategic shift towards becoming banking platforms, much like how Amazon is a platform in retail.”

Was I right? Well, that depends on how you define “begin a strategic shift.” If “thinks about” or “becomes interested in” qualifies as “beginning a strategic shift,” then yes, I was right. If “actually doing something about it” is your criteria, then no, I was wrong.

Platformifi-confusion

Part of the challenge is arriving at an agreed-upon definition of what a platform is. Despite it’s relatively recent use in the world of banking, the concept — as a business model — has been around for a long time (see David Evans’ work on the topic of two-sided business models).

A few articles on The Financial Brand (like this one) have addressed platformification, or as the articles put it, banking as a platform. With all due respect to the authors, their attempt to define seven layers of a fintech platform is confusing. They interchangeably use the terms layers, levels, and levers.

| Platform Levers | Core | Platform Partners |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Scope of Firm | Focused only on core activities. | Define broad array of activities to be performed outside of firm by partners. |

| 2. Product | Own core product stack. | Allow for partners to develop and offer ancillary products. |

| 3. Service | Own core service stack. | Allow for partners to develop and offer ancillary services. |

| 4. IP/Data | Sharing of information. | Define what to disclose to partners. |

| 5. Technology | Modular tech, open source and open standards use, API interface openness. | Interoperability between partner interfaces and firm’s interfaces is key. |

| 6. Relations w/Partners | Decide where on the collaborative/competitive continuum will the company sit. How will relations/decisions and consensus be arrived at? | Collaboration with some partners, competition with others. Different types of consensus mechanisms between firm and partners. |

| 7. Internal HR Organization | Articulate HR between group that focuses on core and groups that focus on platform across product, service, IP/data, technology, partners and C-suite executives within firm. | Develop ability to “speak the same language” as partners. |

( Source: 11:FS )

The constant use of the term “partners” is also confusing. The relationship between a platform (the underlying company, that is) and providers on the platform is not a partnership.

I sell things on Amazon. I doubt Amazon sees itself as being in a partnership with me, nor do I see Amazon as a partner.

Distribution channels aren’t necessarily partners. A partnership is a contractual relationship between parties with shared risk and return. Platform participants have a contractual relationship, but not shared risk and return (for a more ind-depth discussion of this, see The Foolish Fantasies of Fintech/Bank Partnerships).

Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

Build a modern credit card strategy that balances profitability and risk, adopts the latest technology and delivers the customization that cardholders demand.

Read More about Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Vericast’s 2024 Financial TrendWatch explores seven of today’s most critical financial services trends to provide a complete view of the current loyalty landscape.

Read More about Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

What is a Platform?

In the old days, a “platform” was a type of shoe popular among people who went to discos. These days however, in a business context, there are many new and divergent definitions. Here’s my favorite, from a site called Platform Strategy:

“A platform is a plug-and-play business model that allows multiple participants (producers and consumers) to connect to it, interact with each other and create and exchange value.”

There are three important components of that definition:

- Business Model. First and foremost, a platform is a type of business model.

- Plug-and-Play. A platform must enable participants to easily engage — and disengage (which partnerships typically don’t).

- Create/Exchange Value. One plus one has to equal more than two, or there’s no need for the platform.

Three Elements of a Successful Platform Strategy

An article in the Harvard Business Review best describes what a company needs to do successfully execute a platform strategy. It must:

1. Become a magnet. Without the ability to attract a meaningful number of the “right” participants, a platform cannot succeed. Simply having a lot of producers and consumers is no guarantee of success. The platform must attract the right producers (those with the most desirable products and services) and the right consumers (those who the producers in the platform want to do business with).

2. Act as a matchmaker. A platform requires a mechanism for matching consumers to the right producers, and for enabling producers to reach the right consumers who come to the platform. At its most basic level, a search engine can be matchmaking mechanism.

3. Offer a toolkit. The toolkit is what enables producers (and consumers) to easily plug-and-play. This is why APIs are so critical to firms pursuing platform strategies.

Are Today’s Banks Platforms?

In the course of discussing the platformification of banking, I’ve had bankers tell me that their bank is already a platform. I know platforms, and your bank, sir, is no platform. Here’s why:

- Today’s banks are consumer magnets, not producer magnets. Banks do a fairly good job of attracting consumers. But there is practically no focus on attracting other producers, other than the one-off partnerships that a bank pursues.

- Today’s banks only match consumers to their own products or services. The key to successful matchmaking on a platform is matching a consumer to one (or more) of a number of providers. Banks only match consumers with the just one provider’s products — the bank’s. If they even do that.

- Today’s banks don’t have a toolkit. Banks have a mixed track record of integrating the products and services of the firms with whom they develop partnerships with, let alone providing the ability to plug-and-play.

Why are We Even Discussing Platformification?

Why are we discussing this stuff? One reason is because technological developments (i.e., internet, mobile, etc.) have enabled banks to become platforms. But technological change — by itself — is not the only reason. There are two other contributing factors:

- Consumer Demand. For as important as money is to many of us, most of us hate having to manage it. And so we haven’t. What’s truly different about the younger generation(s) is their involvement with managing their financial lives. This gives rise to interest in, and demand for, a wide range of tools and features to help manage one’s financial lives. Tools and features that a single bank would be hard pressed to develop, launch, support, and make profitable.

- Economics. Banking’s traditional business model is eroding. Interest rates are at a historical low, lending opportunities are being attacked by newcomers, the ability to raise interest rates on credit cards has been regulated away, fewer consumers revolve their card balances anyway, and making money through overdraft fees is hardly a long-term strategy. In short, banks must explore new business models.

Hence, the interest in- and need for a platform. There is a more practical reason.

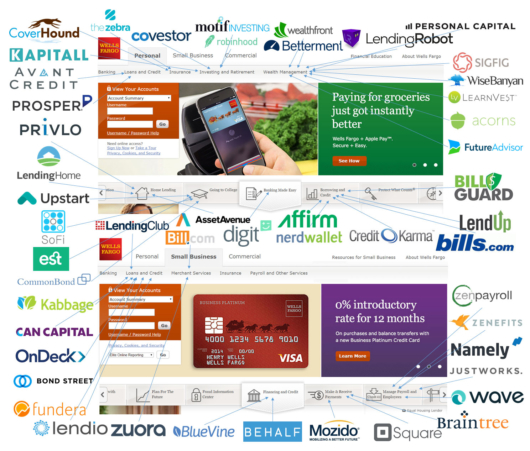

The following picture has become popular among fintech pundits, and used in numerous articles and conference presentations:

It shows the Wells Fargo home with arrows pointed to fintech startups that purport to provide the various products, services, and features provided by Wells Fargo’s website. The message is that the traditional bank is becoming “unbundled.”

I don’t see it that way.

Re-Architecting The Hierarchy of Needs

What’s happening is that the hierarchy of needs in banking — security, movement, and performance — are being rearchitected. And with all this technological development comes a challenge: Who is going to pull this all together in some coherent, cohesive way for consumers?

The answer is an organization with a platform-based business model.

Consumers don’t know many of the startups in that ubiquitous “platformification graphic,” and I don’t think they care to know. Consumers don’t want to have to work to find out which companies do what, if they’re any good, and if they’re safe to do business with. They want someone or something to make it all easy for them.

They want a platform.

Unlocking Digital Acquisition: A Bank’s Journey to Become Digital-First

This webinar will offer a comprehensive roadmap for digital marketing success, from building foundational capabilities and structures and forging strategic partnerships, to assembling the right team.

Read More about Unlocking Digital Acquisition: A Bank’s Journey to Become Digital-First

Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

83% of FI leaders agree investing in AI is essential for 2024 but how you leverage AI is instrumental in success and meeting customer expectations.

Read More about Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

Becoming a Banking Platform

Today’s economic realities may be spurring an interest in new business models, but some realities exist:

Becoming a platform is hard. Amazon’s history provides a lesson for platformification. It spent the better part of its first 10 years of existence becoming a consumer magnet. In 2006, it launched Amazon Web Services, which really became the basis of its platform “toolkit” and helped solidify its ability to become a producer magnet. All told, Amazon’s platform strategy is 20 years in the making.

Few banks have the stomach to transform their business model. Here’s reality: Unless your bank is on a burning platform (pun intended), business model change ain’t going to happen. And even then it’s no guarantee. A bunch of senior execs are clinging to the lifeboats hoping to reach Retirement Island, and the board — well, really now, you weren’t looking to the board for business model transformation change, were you?

Few banks have the strategic vision. There’s nothing like spending 20, 30, even 40 years in an industry to solidify your view of what drives success in that industry. Platformification is a few steps removed from that view.

Few banks have the resources to build a platform. This, however, is a short-term, not a long-term, challenge. Twenty years, when we pundits told banks they would need websites, and online banking platforms, they said “we don’t have the resources to do that.” They were right, but the vendor community filled the gap. As it will with a “bank-as-a-platform” capability. [Note to fintech vendors: What you have today is nowhere near this capability].

The regulatory environment (in the US, at least) is not supportive (or even clear). An American Banker article about the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (or as I would prefer to call it, Office of Contradictory Comments) reported that the agency said:

“Making strategic moves to innovate with new technology-based banking involves assuming unfamiliar risks, but banks may face heightened risk if they do not innovate. Banks should have effective risk management to ensure such innovation aligns to their long-term business strategies.”

How could a bank with no experience as a platform ensure that it has “effective risk management” to align with that strategy? Furthermore, the agency’s discussion of “responsible innovation” leaves much to be desired.

The Future of Banking Platformification

None of this, however, takes away from the business potential of a true banking platform. An institution that successfully executes on a platform strategy creates new revenue streams, creates diversification against future downturns in its core businesses, and creates a new type of relationship with consumers.

In retrospect, I was probably wrong. 2016 won’t see a strategic shift towards platformification among existing banks. The more likely scenario is that over the next five to 10 years, one or two players will emerge with a banking platform strategy, and shake up the strategic viewpoints of other banks.

That’s not meant to take anything away from the work of a few banks, BBVA in particular. The bank’s API market, both in the US and Spain, has begun to provide the toolkit necessary to become a platform, and its work in developing relationships (through investments and, yes, partnerships) has laid the groundwork for broader third-party provider involvement.