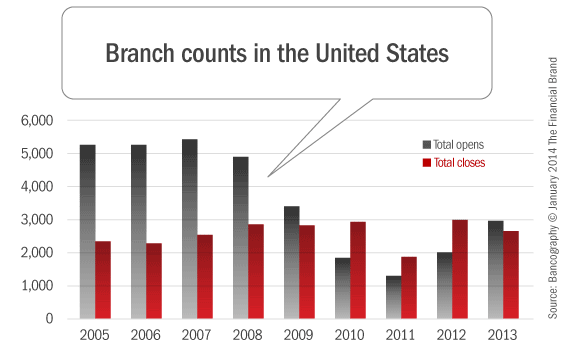

As electronic channels have gained popularity for banking transactions, many branches have seen an accompanying reduction in teller transaction demand. This has led many industry commentators to predict widespread branch closures in the near future, a prediction further fueled by declines in branch openings and in absolute branch counts in 2010 – 2012. However, a reversal in those trends in the most recent year suggests that the declines of 2010 – 2012 were more in response to the financial crisis and the accompanying large-scale mergers than of any pervasive industry conclusion that branches no longer carry value. Several statistics rom the most-recent FDIC and NCUA deposit reports confirm ongoing support for branch networks.

Reversing three years of declines, the number of bank branches in the United States increased by more than 250 units in the 2013 FDIC reporting year. Banks opened almost 3,000 branches during the past year, the highest level since 2009. Those opens were offset by more than 2,700 branch closures, a substantial level but still lower than the 3,100 closures of the preceding year.

The net number of credit union branches declined last year, but the decline was almost entirely attributable to the absorption of small, mostly single-branch credit unions by larger institutions. At the top of the industry, among credit unions with at least $500M in assets, total branch counts also increased, though only modestly.

The rebound in branching spanned a broad portion of the industry. More than 1,000 institutions increased their branch counts in the 2013 FDIC reporting year, while only 400 contracted their branch networks. For comparison, note that in the 2012 reporting year, 440 institutions added branches while 460 reduced their networks. So more institutions added branches, and fewer institutions reduced branches in 2013 than in the previous year.

As in prior years, most closures were concentrated among a few institutions that implemented sizable branch-closure efforts. Bank of America was most prominent in that effort, reporting 200 fewer branches in June 2013 than in June 2012. SunTrust reduced its network by almost 100 branches, while PNC, HSBC and Capital One each reduced their networks by 40–70 branches.

Industry Cloud for Banking from PwC

See how PwC's Industry Cloud for Banking can help solve everyday business challenges.

Why Industry Cloud for Banking?

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking helps deliver personalized products and services that today’s customers expect.

The 400 banks that decreased their branch networks trimmed an aggregate 1,500 branches, but just 15 institutions accounted for half of that reduction. Further, in an opposing strategy, JPMorgan Chase added more than 100 branches over the past year. US Bank, Wells Fargo, and Woodforest Bank also increased their networks by 20 or more branches.

While the decline in branches has apparently stabilized and even moderately reversed, mergers and institution failures have yielded continued erosion in institution counts. The FDIC reported 6,900 banks and savings institutions as of June 2013, a decline of 400 institutions from two years prior and of more than 1,000 institutions from four years prior. The NCUA reported 6,700 credit unions as of June 2013, down 550 institutions from two years prior and more than 1,000 institutions from four years prior.

In that institution counts have declined at a much greater pace than branch counts, the average scope of branch networks, in terms of number of branches per institution, is increasing. This suggests that individual financial institutions are not reducing the scope of their networks in terms of the number of submarkets in which they offer branches to consumers. Rather it appears that branch reductions are primarily targeting the overlaps that arise from mergers and acquisitions.

The branch network represents a substantial component of a financial institution’s operating burden, both in terms of the capital investment impounded in the facilities and equipment and the salary and maintenance expenses required to operate the branches. Further, there is ample evidence that alternate channels are reducing consumers’ dependence on branches for routine paying and receiving transactions. However, the branch remains the predominant channel for account opening, which of course is the primary objective of the facility, as well as an essential means of reinforcing the institution’s convenience and availability. While many younger consumers have embraced a primarily electronic means of banking, the most profitable segments, including small businesses, affluent consumers and seniors, continue to ascribe value to nearby branch convenience.

Although the financial downturn of recent years may have rendered branch closures imperative for expense control at some institutions, the stabilization of branch counts confirms that bankers understand the value of a continued physical presence and suggests that judicious branch expansion will continue as economic circumstances allow.