We are all familiar with dynamic pricing in the hospitality, travel and entertainment industries. We may have even encountered dynamic pricing in e-commerce, probably without knowing it. At its core it is flexible pricing based on current market demands, fine tuned by data analytics where sophisticated algorithms account for time of day, supply, demand, competitive offerings and target profit margins. We have either benefited from – or taken a hit by – what we perceived were bargains or price gouging. Booking a flight or hotel room during peak travel periods, purchasing a ticket to a weekend sporting event or even Uber surge pricing are all examples.

But what about dynamic pricing applied to the financial services industry. Can the banks or credit unions apply dynamic pricing in the same manner other industries have applied it – as an intermediating algorithm, matching supply and demand? Prices of financial services take into consideration operational costs, profit margins, and demand, but at its core, financial service or product pricing is predominantly constructed around risk. A loan, an insurance product, a payment service is usually priced based on risk assumptions.

Let’s focus on a borrower who wants a loan from a bank. The bank will assess the risk of that borrower, and will come up with a rate that is directly linked to that risk and to the bank’s cost of capital, which in turn is based on market based rates. The borrower will, in turn, be very price/rate sensitive, shopping for the best available rate. The only variable in the equation is the bank’s margin embedded in the loan’s rate. The floor on that margin has to align with profitability standards and liquidity coverage requirements.

Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

Build a modern credit card strategy that balances profitability and risk, adopts the latest technology and delivers the customization that cardholders demand.

Read More about Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Learn how to enhance your brand’s local visibility, generate more leads, and attract more customers, all while adhering to industry regulations and compliance.

Read More about The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Dynamic Pricing in Lending

So the real question is … can a bank or credit union truly provide dynamic pricing on a product, like a loan, given the constraints of price elasticity? The same can be asked of an alternative lender, although an alternative lender may have more flexibility given the lower amount of regulatory oversight.

We believe the answer is more likely to be no, although a traditional bank may deliver more granular rates based on better underwriting and data analytics. True dynamic pricing is less likely.

Does this mean that dynamic pricing is an elusive holy grail for financial services incumbents? Not quite, especially if we introduce the added dynamic of client relationships. If our borrower from the above example also has a checking account, a savings account or an insurance policy with the bank, then dynamic pricing can be viewed along two vectors: a) relationship pricing and b) pricing execution.

Note that we are not using the term “product pricing” here since the emphasis is on relationship pricing where the customer’s portfolio of products used becomes the basis for pricing. The overall relationship is taken into consideration, including the operational costs, margins and risk of the consumer’s portfolio with the institution, not just the products in isolation. This requires a shift from being product-focused to being relationship and service-focused.

As for pricing execution, a shift also has to happen – one linked to how technology is architected, deployed and used. One where siloed systems and siloed data analysis are phased out for more holistic approaches. Imagine a system architecture that would allow for dynamically changing pricing individually or in the aggregate based on the entire product usage profile of a consumer. This pricing could be formulated based on internal goals, customer asks and/or competitive offerings, where the lifetime value (LTV) of the customer and the lifetime value to the customer are constantly weighed and optimized without one losing to the other materially. The results of this type of model can be quite powerful.

The benefits of such an approach are obvious and strategic:

- Increased customer loyalty and stickiness

- Enhanced customer experience

- Increased ability to rebundle and cross sell

- Increased contextual awareness of customer needs

The challenges are no less obvious. First, current core systems for traditional financial institutions are silo-based. Secondly, organizational structures are also silo-based. Thirdly, management incentives are also product and silo-based. Finally, and not unsurprisingly, most relationships are also viewed from a silo perspective both on a product and household structure basis (husband, wife, couple, family).

Customer Lifetime Value

Looking at the concept of consumer lifetime value (CLV) in a little more detail, the tenant that underpins the notion is that “some customers are more equal than others”, and it measures long-term value over a current quarter’s profit. Boiled down to the basics, it takes the present value of the future cash flow (profitability) attributed to a customer during the entire potential relationship with the bank. In other words, the profitability of loyalty.

This equation can be a little misleading, since profitability is measured by past consumption of services (revenue minus operational costs), and value is a forecasting exercise that involves factoring in the declining value of money over time. This makes this calculationsignificantly more vague to measure than past profitability. What it boils down to, though, is how much the bank is willing to pay to acquire the customer against how much the bank is willing to pay to avoid losing the customer. Customer lifetime value (CLV) is really a dollar value of the asset, the customer.

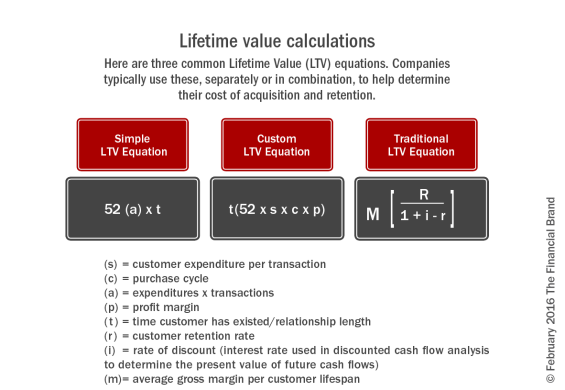

Mathematically it looks like this:

CLV ($) = Margin ($) * (Retention Rate (%) ÷ [1 + Discount Rate (%)]) * Retention Rate (%)

When there’s a fight for increasing deposits in a low interest rate environment, and interest generated revenues are tight, cultivating CLV is a strategy that directly works to grow wallet share, especially amongst market segments where wallet share is low. There’s a direct correlation between additional marketing spend to target high potential CLV customers who currently have low wallet share with the bank.

Wallet share relates to customer loyalty and stickiness. And dynamically pricing product bundles attracts additional customer wallet share. We hinted at relationships being viewed in silos, but once those silos are broken, and the bank has a full view of the customer’s portfolio, and prices are at the portfolio level instead of the product level, forecasting the lifetime value becomes a valuable exercise.

When Your Customer Wants a Divorce

There is one paradox in all of this, and that is a sense of customer apathy – the effort it takes to switch bank accounts. Customers may not be as apathetic as predicted.For instance, when the UK launched the initiative in 2014 to make switching current accounts easier, nearly a quarter of a million account holders switched as they looked for better offers, service, and loyalty programs. In fact, some banks launched new loyalty rewards to try to stem to leak, with some success (interestingly, when the switching surge ended, the vast majority of market shares among the primary banking organizations remained the same).

For some customers it was about service. For others, it may have been the high fees or the poor user experience. For some of those who didn’t switch, apathy may have been the most plausible reason.

Customer Experience and Satisfaction in CLV

Let’s look at the peer-to-peer alternative lending market and the growth of P2P payments, and how consumers are willing to abandon traditional bank offered products in search of a better priced, more customer-friendly option. Ernst & Young published a report in 2014 on the staggering growth of P2P lending (both for consumer and business). With nearly a 75% growth rate year over year, the P2P lending surge cannibalized a considerable chunk of the bank lending market. That growth was fueled by consumers jumping ship to set sail with alternative lenders. This growth in the P2P lending market shows no signs of slowing down.

P2P payments is another, some say better, customer service experience alternative, with nearly $90 billion worth of customer transactions leaving the traditional bank market. Both of these P2P alternatives represent potential profitability that traditional banks are losing, with the resultant negative impact on the lifetime value of the customer caused by a fractured, multi-point, conglomerate of service providers.

The obvious win-win-win is a bank – alternative provider or fintech partnership that brings these services into a one-stop-shop for the customer. Lifetime value for both bank and customer married, living under one provider roof.

Dynamic Pricing Impact on Loyalty

Since the benefits of dynamic pricing increase customer loyalty, stickiness, customer experience, as well as provide opportunities to re-bundle, cross sell and actually meet a customers contextual needs, it’s obvious that dynamic pricing is at the root of the customer lifetime value.

It also gives the customer choices to create a portfolio of services that exactly meet their needs – the more flexible the pricing, the more flexible the bundle, the more the customer “delights” in the service provider. Choice enhances the customer experience, reaffirms institutional trust, and helps promote financial health for a valuable lifetime relationship.

It also staves off competition, since it’s the differentiator in a market of “same old, same old” bank providers.

So it begs the questions: 1) How feasible is it to achieve dynamic pricing in financial services? 2)When will that happen? and 3) Why aren’t banks responding more vigorously to the call to rebundle?