In the 1970s, the first home computer was introduced. Almost two decades later, the World Wide Web made its debut, thus ushering in a revolution that enabled universal access to the internet by the early 1990s. This, needless to say, had a cascading impact on multiple industries — banking included. Banks were still all about the brick-and-mortar model until the late 1990s. It wasn’t until the mid and late 1990s when these entities began seriously investing in internet banking technology.

By the time web banking became popular concurrently with widespread broadband availability, the new revolution was knocking on the door in the form of mobile technology. Mobile phones hit the market in the 1980s, but banking on these devices was limited to mainly SMS or USSD-based transactions. It wasn’t until smartphones arrived in the late 2000s which led to the rise of mobile banking applications in the 2010s.

Upon closer examination of the timelines, it is clear that web and mobile (app) banking found their feet in the industry 10 to 15 years after their debut. Simply put, these mediums followed the normal route of uptake, where the key drivers were the necessity of infrastructure and availability at affordable costs required before gaining sufficient acceptance levels. In other words, technology becomes popular when it is available round the clock, affordable, convenient, reliable, safe, and easy to use.

Consumer Views on Digital Banking Services

Today digital banking technologies (web and mobile) are well entrenched in the space. With the aim of gathering consumer perspectives on the use of these digital methods, we conducted a Digital Banking (Retail) Consumer Survey in mid-2020 across continents.

The survey focused on web and mobile application-based banking. Respondents were asked for their views and perspectives on existing digital banking services. The survey included 327 participants from Latin America, APAC, Europe, and Africa. A majority of the respondents were from Latin America and APAC, covering Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and India. There was significant participation from other countries as well, including the U.K., Norway, U.A.E., Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa.

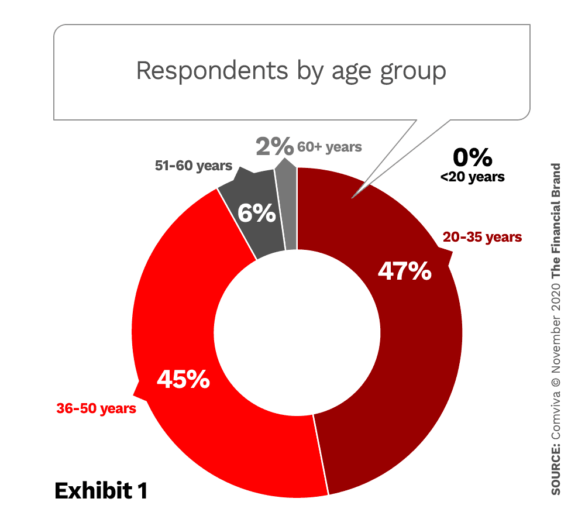

Consumers from the age groups 20-35 years (47%) and 36-50 (45%) accounted for the majority of participants, as shown in Exhibit 1. About 8% were above 51. This helped us capture the perspectives of customers using banking services right from the 1980s, assuming customers would start using financial services in their early 20s.

The geography spread in the sample size balances out the possible regional biases, as the survey covers all types of income-level countries. About 79% of the participants were from the working-class, either salaried or owning a business, while the rest of the 21% were retired, homemakers, or students (over 20 years old).

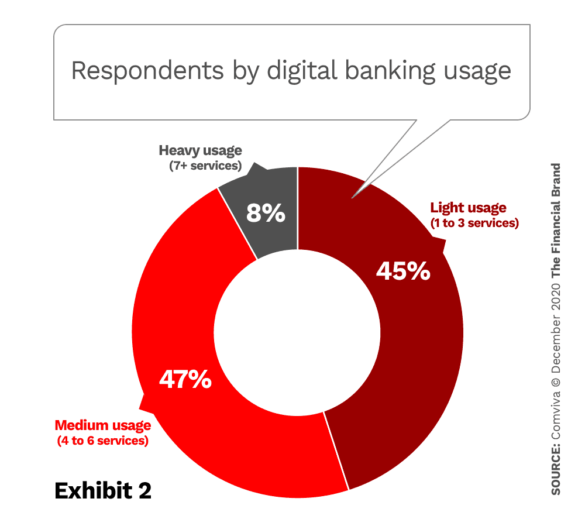

The participants were further categorized based on their usage levels namely low-usage, mid-usage, and high-usage customers. Categorization of use indicates maturity among the participants with respect to digital banking service consumption via the web and mobile applications. Interestingly, 55% were either in the mid-usage (47%) or high-usage group (8%), as shown in Exhibit 2.

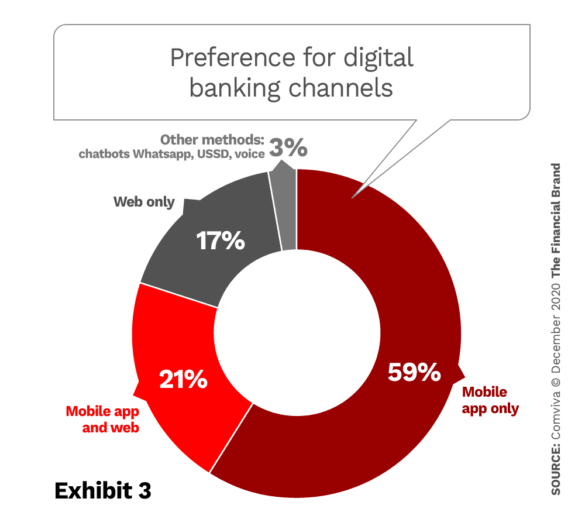

As consumers typically used multiple digital banking methods, the preferred channel(s) being used also came into focus. In fact, this question elicited surprising responses. 17% of the respondents leveraged the web only, while 21% used both, the web and the mobile application, and a whopping 59% used only mobile applications, as shown in Exhibit 3.

Upon probing a bit deeper at country-level data, in Brazil, over 82% of participants preferred using only mobile applications for their banking needs. In contrast, Colombia stood at 59%, India at 56%, and Argentina at 37%. In Argentina, 19% used both mobile application and web. Indisputably this is a remarkable trend and supports the idea of financial institutions investing more into these digital channels especially mobile application.

The study tested three hypotheses important to the future of digital banking. These are discussed in detail below.

Hypothesis 1: Customers Always Expect Their Banks to Provide a Host of Financial Services

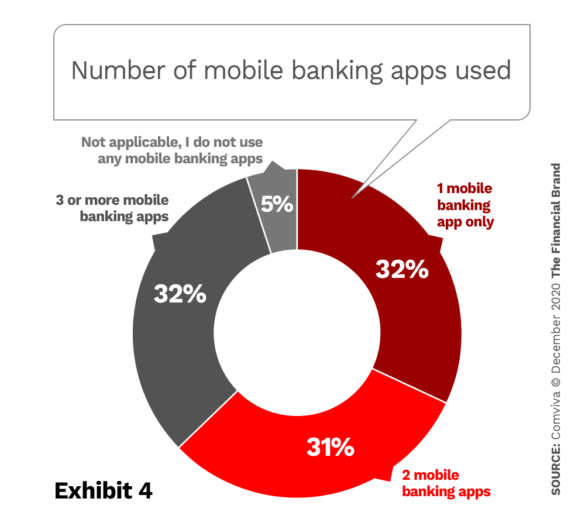

Interestingly 63% of respondents used two or more mobile banking applications (as shown in Exhibit 4), which was attributed to two key reasons — numbers of services and experience.

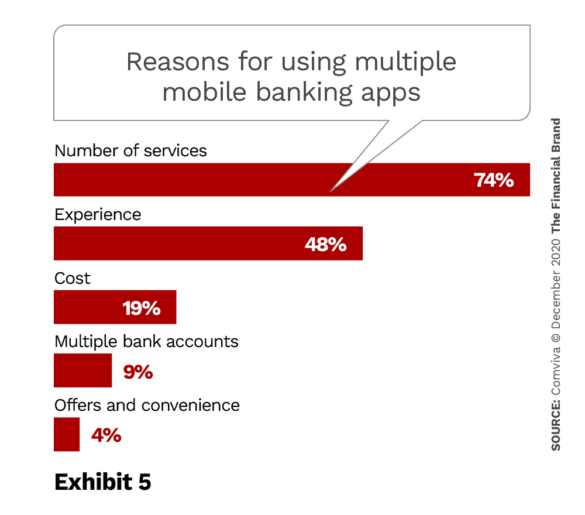

Survey respondents had a choice of selecting one or more reasons for using multiple mobile banking app. 74% of the total respondents who use two or more mobile banking apps quoted ‘Number of Services’ as one of the reasons for using multiple mobile banking apps, as shown in Exhibit 5.

It clearly is a no brainer to say that the number of services being offered matters to consumers, but not necessarily from a single bank! At times, though, it is counterintuitive to say that banking applications do not offer many (or most) services.

Responses also indicate that the majority of mobile banking applications that consumers use do not offer a one-stop-shop service. The good news for financial institutions, however, is that consumers value service level differentiation. It offers a level playing field which is important for neobanks and fintechs.

“Experience” is another critical factor as 48% of the total respondents who use two or more mobile banking apps quoted it as one of the reasons for using multiple mobile banking apps. Hence, the importance of service-differentiation and consumer experience cannot be ignored. This helps us validate the first hypothesis that consumers really value the number of services being offered by their financial institutions.

Hypothesis 2: Customers Don’t Expect Their Banks to ‘Know’ Them in the Digital Era

People using financial services since the 1880s and 1990s used to visit bank branches frequently, which, was limited by the ushering in of ATMs and digitization, but not completely eliminated. So, do consumers really not mind if their financial institution doesn’t “know” them in the present digital and internet era?

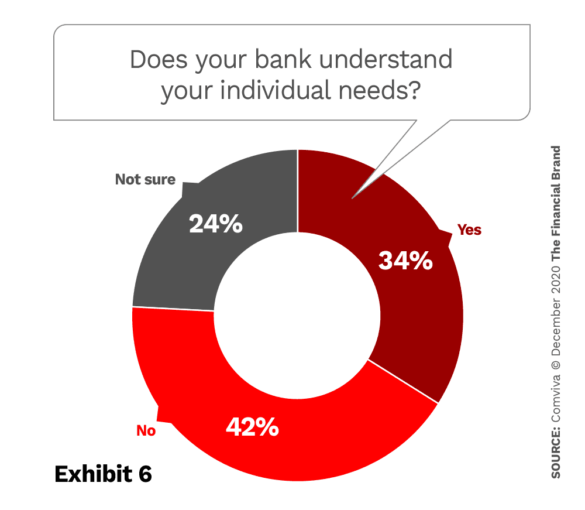

The survey revealed an interesting take. When asked whether their bank understands individual needs, only 34% of consumers agreed. 42% firmly disagreed, stating that their bank doesn’t understand specific needs and personal situations (Exhibit 6). While respondents who aren’t sure are typically disregarded, in this case, their response triggered the fact that perhaps banks are unable to manage customer relations or at least the perception of individualized consumer engagement.

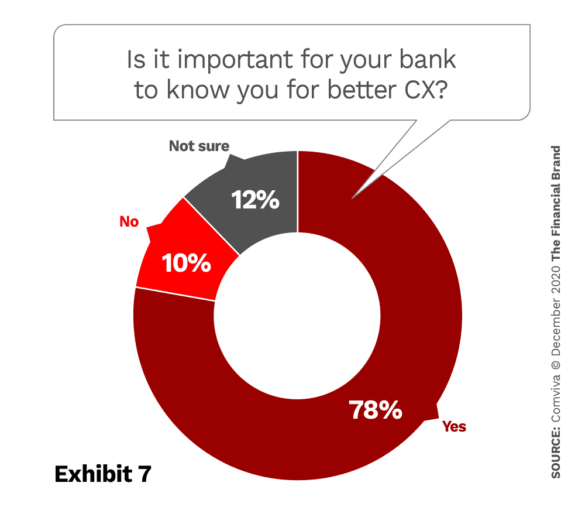

When we asked consumers whether it is important to them that the bank knows an individual’s needs, the ambiguity of responses shown in Exhibit 6 faded away. A massive 78% of participants (Exhibit 7) registered that the bank should know their individual needs for a better banking experience. It was less important to a meager 10%.

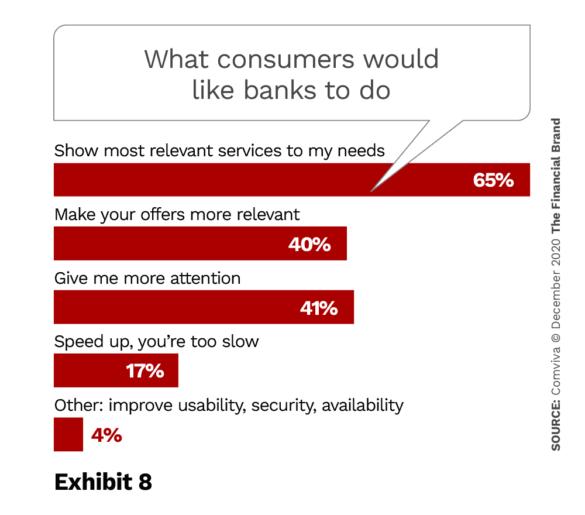

Survey respondents were also requested to make recommendations to banks, as a checklist of sorts. They had a choice of selecting one or more recommendations. On one hand, consumers value the number of services the bank offers, while, conversely, they demand relevance as well. It becomes overwhelming to the majority of the people to see many services in their account dashboard when they actually use less than 10% of it.

All the top three consumer recommendations to financial institutions are linked to being relevant to their needs, as shown in Exhibit 8. 65% of respondents want to see most relevant services catering to their needs, 40% of respondents want financial institutions to share more relevant offers and 41% recommend banks give consumers more attention.

Financial institutions would have to acknowledge the fact that the consumers of the present era don’t want to be left alone and value ‘personalization’ way more than we think otherwise. The second hypothesis, hence, is disproved.

Hypothesis 3: No Customer Wants to Pay for Web or Mobile Banking Services

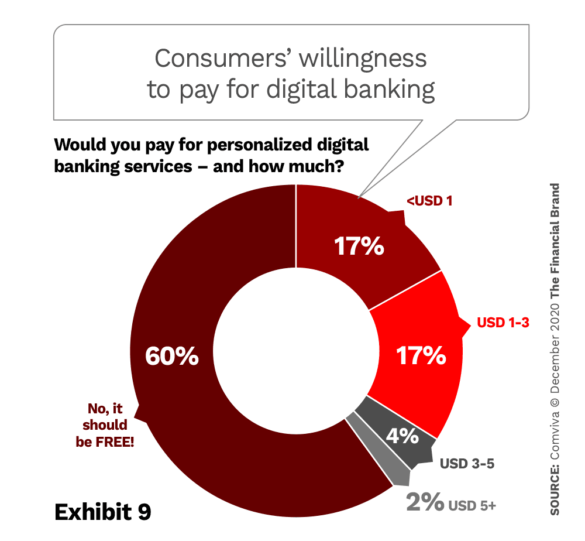

We were, in all honesty, debating whether to term this a hypothesis or a myth. Here’s why: About 40% of participants said they wouldn’t mind paying for digital banking, if the services were ‘personalized’. 34% were agreeable to paying anywhere under $3 per year, as shown in Exhibit 9.

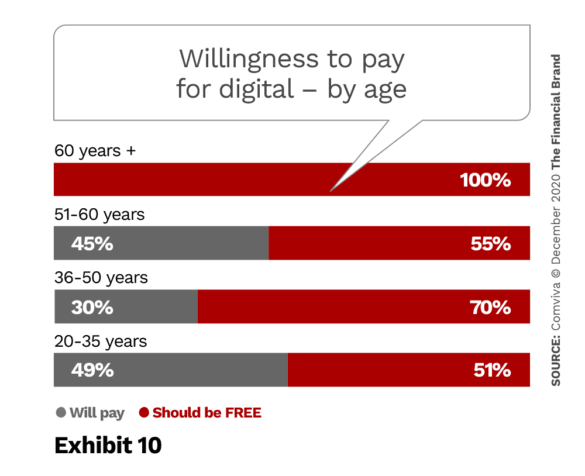

An age split (Exhibit 10) reveals that the percentage is higher in the below 35-year age group, with 49% stating their willingness to pay for such services. At the extreme end is the over 60-year age group, with all 100% demanding this service for free.

Overall, a significant 40% of the group was willing to pay for personalized digital banking services, thus disproving this hypothesis.

Analyzing the Survey Responses

Across age groups and continents, openness and acceptability for digital financial services being offered via web and mobile applications was witnessed. This would certainly evolve further with voice-enabled financial services being pushed in the market and newer technologies being developed rapidly. Keeping in mind the myth that customers were afraid of the security of internet and mobile technologies, the survey was an eye-opener and reinforces the idea of the push for digital banking strategies via these new-age channels.

Analysis of the first hypothesis revealed two things.

First, digital financial services is still not a zero-sum game. From the institutions’ perspective, there are many untapped consumer segments in the market looking for more and better services. To name a few: unbanked people requiring basic financial services; digital lending in real-time (with minimum or digital documentation); smooth and faster international fund transfers, etc. This is where fintechs are giving tough competition to established financial institutions.

Second, consumers are open-minded in receiving services from multiple financial institutions. The concept of “super-apps” — where financial institutions can bundle everything in a single mobile application — is appreciated, but as a practical matter, few may be able to achieve such dominance.

In reality, each financial institution and fintech must keep differentiating based on services, experience, costs and — not to ignore — their unique marketing techniques.

Several neobanks and fintechs support this fact. For example: NuBank, Brazil; TransferWise, U.K. (worldwide); Fidor, Germany; N26, Germany; Greenlight, U.S., Alipay, China and Paytm, India. There are many more.

With newer technologies gaining traction and regulations being amended worldwide to accommodate newer ways of financial services delivery, consumer needs will guide the market development by itself. Increased competition among financial institutions and fintechs will deliver the necessary innovation to augment the growth. Predictive and prescriptive data analytics, open banking (via open APIs) and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies will drive consumer-oriented financial services in the coming years. It will be interesting to see more applications of these fast-evolving technologies in the financial domain. One such application is personalization which was our central theme for the second hypothesis.

It’s a balancing act between ‘offering more services’ (results for the first hypothesis) and ‘showing relevant services first’ (results for the second hypothesis). With the applications of predictive/prescriptive data analytics and AI, this equilibrium can be attained with some dedicated efforts.

For example, let’s say ten banking services are very much relevant for you in general, and you expect your financial institution should offer them all. But in a given situation you need only one service, say availing a car loan. You have been looking to purchase a car over the last few days. Now you are about to close a deal. At this stage, your financial institution offers a car loan that is perfect for your needs. How do you feel? Happy! What is the likelihood that you would go for it? Very likely!

As not all customers would be financially educated, the customer may also seek the right advice from financial institution in choosing the car loan product. Rather than exploiting this situation in its own favor, if financial institution really intends to help and personalize, it would suggest the right car loan product for you with the help of analytics and AI models.

If financial institutions miss the chance, some fintech will be in line to address this gap for consumers. That’s what personalization can do for financial institutions and consumers when used in the right combination of technologies. The touch of personalized engagements from the past decades can be brought back by creating such relevant digital experiences.

We will not dwell too much on the results of third hypothesis mainly because it’s linked to every financial institution’s business model whether they want to charge for the personalized digital experience or not. Offering personalization for free is one type of marketing strategy while charging for it could be the another tactic. The vital point is that a significant number of consumers may want to pay for the personalized digital experience as it adds a lot of value to most of them.

To sum up, the survey responses indicate how consumers perceive their banks and the present state of digital banking services being offered by financial institutions. Consumers no longer compare the digital experience of one bank with that of another, but pitch it against their experience using Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google, Uber, LinkedIn and fintechs.

Lines have blurred between traditional financial institutions and new-age technology companies offering financial services. At certain stages, the industry will get more doses of revolutionary technologies to take quantum leaps for multi-fold progress. It is practically obligatory that financial institutions’ digital banking transformation strategies evolve further to accommodate newer dimensions demanded by the consumers.

About the Author

Yogesh Joshi – General Manager of Business Development, Digital Financial Solutions – is an experienced professional in business development, consulting and business analysis with a demonstrated history in mobile payments and digital banking. He has worked extensively across Europe & Latin America, with additional exposure in Asia and Africa. In the midst of digital banking era, he enjoys studying consumer (retail) banking trends and application of various technological evolutions to consumer banking domain. Note: We would also like to thank Sudarshan Kidiyoor (IIM-I, Summer Intern 2020 at Comviva) who helped create and complete the consumer survey.

About Comviva

Comviva is the global leader of mobility solutions catering to The Business of Tomorrows. The company is a subsidiary of Tech Mahindra and a part of the $21 billion Mahindra Group. Its extensive portfolio of solutions spans digital financial services, customer value management, messaging and broadband solution and digital lifestyle services and managed VAS services. It enables service providers to enhance customer experience, rationalize costs and accelerate revenue growth. Comviva’s solutions are deployed by over 130 mobile service providers and financial institutions in over 95 countries and enrich the lives of over two billion people to deliver a better future.