Bank and credit union executives seeking to digitize their operations can learn from Charles Babbage, who conceived the programmable computer in the 1830s – during the Steam Age. His simple strategy for automating knowledge work can accelerate today’s digital banking transformation efforts. Babbage believed in applying factory floor “industrialization” principles, such as the division of labor, to knowledge work.

He divided complex mathematical tasks into simpler, repetitive subroutines – think of knowledge work assembly lines. Next, he sought to automate these using the clockwork technologies of his day, conceiving his Difference Engine, a 15-ton, mechanical “knowledge work factory.”

Early digital knowledge work factories in banking – ATMs – appeared in banks by the late 1960s. But progress toward digitization stalled, and by 1994 Bill Gates called banks “dinosaurs” destined for imminent digital oblivion. Now, fintech start-ups dream of similar digital extinction. Although banks still hold the high ground, most agree they need to transform their digital efforts.

Babbage’s proven early strategies for knowledge work automation can help improve the transition to digital. The first step is to apply factory floor “industrialization” principles to banking. Divide complex banking operations into simpler, repetitive subroutines – knowledge work assembly lines. Next, automate using today’s technology. The result: digital knowledge work factories for banking.

Rebar Niemi of Intellectual Ventures has written of Babbage, “At the heart of each of his projects is a procedure. Break an operation down into smaller operations, increase its efficiency and precision, analyze and compare possible alternative strategies, and quantify success.”

Here’s how that industrialization redesign might look in a bank or credit union today. Break down the intake operations for new loan applications, such as home equity, mortgage and consumer loans. Create specialized assembly lines and standardize the most common remediation activities, such as “missing information” or “unsigned document.” Consider automating the most standard activities. And reduce the root causes upstream – clearer instructions, simpler forms.

This is a radical change. It replaces a familiar but failed century-old strategy for office work automation. Vendors can provide technology that compels users to industrialize these activities.

Why Industry Cloud for Banking?

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking helps deliver personalized products and services that today’s customers expect.

Instant Messaging. Instant Impact.

Connect with your customers and provide lightning-fast support as effortlessly as texting friends. Two-way SMS text messaging is no longer optional.

A Compelling Illusion: Technology-Driven Industrialization

In business, large-scale automation technology for office, or knowledge, work arrived in the 1920s. These new mechanical filing systems, calculators and punch card tabulating machines could, it was claimed, deliver breakthroughs in productivity. However, the benefits required standardization of the office work prior to automation – industrialization.

Despite the productivity revolution that industrialization was delivering on the factory floor, office executives resisted applying it to their work. No problem. Office automation vendors of the 1920s simply modified their sales pitch. Sales materials and scripts from that period promised customers that installing the automation technology would “gently force” office workers to change their work activities, to standardize, to use the equipment. The strategy of technology-driven industrialization was born.

The strategy fell short on productivity. Reports from the time describe abandoned, underused technology and minimal productivity gains. But as a sales strategy the illusion remained compelling. Today digital vendors still claim their technology will gently force knowledge work industrialization. A century later, this strategy is still falling short on productivity gains.

For example, a global bank invested in a high volume, loan underwriting workflow technology for its mortgage operation. Management sought to “digitize” the business processes for originating and servicing loans, eliminate paper documents, reduce cycle time and balance the workload across employees in multiple locations. They expected productivity gains of 30 percent or more.

The vendor stressed the fact that the business processes were “built in” the technology. Implementation would deliver a ready-made digital assembly line for loan operations. This would gently force employees to standardize their work activities to use the workflow technology. The technology would not only industrialize the work but also enable transparency for operating activities, provide status reports on work-in-process and monitor employee productivity.

However, executives had never managed the productivity of the operation or the employees. That meant that virtually no operational statistics existed. No data were readily available for throughput volume, cycle time, error rates or service quality. Instead, the organization was managed by comparing thousands of ledger-line budget costs from one period to the next. Written documentation of procedures or business processes had always been minimal. Employees operated on informal tribal knowledge. Their individual performance was evaluated qualitatively, once a year.

Consequently, the implementation team lacked the operational detail needed to tailor the technology’s generic, built-in processes to those of the bank. They were unable to load the new system with operational procedures or historical productivity data. That meant that it was impossible to deliver the promised digital assembly line at a meaningful level of detail. Instead, the technology served merely as a digital conveyor belt. Paper was eliminated. However, the work-in-process simply continued its zig zag, back and forth journey through the organization in digital form via the costly new workflow tool.

Standardization progress was minimal. Without the rigor of an assembly line, workers were free to continue performing their tasks on their individual computers in a one-off manner. The individual silos remained. Once completed, workers entered results into the new workflow system. This defeated the objective of real-time operational transparency and status reporting.

The bank had pursued the same technology-driven industrialization strategy popularized in the 1920s and achieved the same results. The automation was acquired and deployed, but it was underused and delivered negligible productivity gains.

Worst of all, the technology investment served as a form of “inoculation” against further improvement or even investigation. After all, executives reasoned, they had adopted the latest technology. Surely, any further improvement could only come from the next generation of technology, perhaps robotics. Their technology vendors agreed.

Digital Banking Requires Factory-Style Management

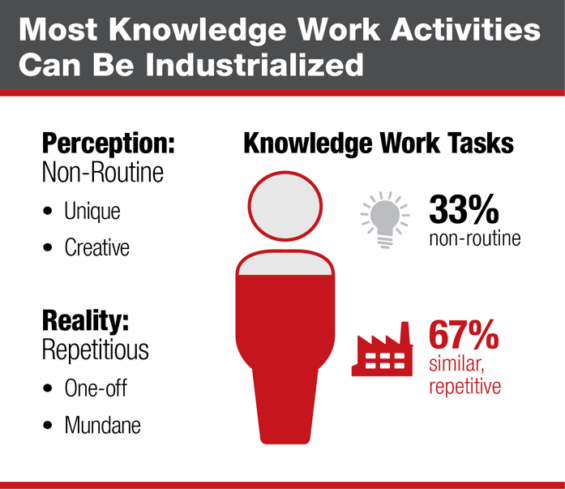

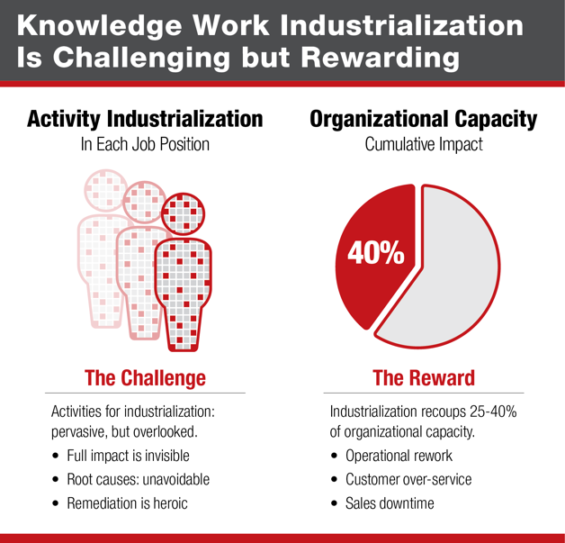

In the example above, the characteristics of the loan group operations were ideal for digital automation, but not by putting the technology cart before the work task horse. Just as in 1920, time and effort should have been invested to determine that two-thirds of the work activities were similar and repetitive. Understandably, executives’ failure to industrialize might be attributed to unfamiliarity rather than unwillingness. But other, simpler examples demonstrate that executives are also reluctant to manage digital knowledge work factories with a priority on productivity.

A super-regional bank implemented a digital document capture and centralized processing technology throughout its far flung branch network. The equipment, although highly automated, still required human operation with rigorous management oversight – just like factory floor equipment. It required standard operating procedures with factory-style daily reporting on productivity, service and quality.

Executives were reluctant to implement this factory-style management in the bank. Consequently, employees operated the new technology based on their individual, inconsistent views of efficiency. Some employees batched documents by type, others did not. Some transmitted files continually throughout the day, others waited until the end of day. About 15% of the employees even skipped daily transmittal, preferring to transmit whenever they felt the batch was large enough to merit the effort.

The digital technology was designed and implemented properly. And yet, due to the reluctance to implement factory-style productivity management, the bank failed to achieve the targeted benefits: Productivity remained flat. No improvement was made in service quality, error reduction or timeliness.

For funding and technical reasons, Babbage never finished building his Difference Engine. That would not happen until 1991, when the London Science Museum completed it. Businesses have been similarly slow to adopt his views on industrializing knowledge work. Executives still want the cart to pull the horse.

“[It may] appear paradoxical to some of our readers,” he wrote, “that the division of labor can be applied with equal success to mental as to mechanical operations, and that it ensures in both the same economy of time.”

Don’t Replicate Bad Processes

Everyone is talking about automation, digitization, robotics, etc. – but not about preparing for automation. Installing new digital banking technology doesn’t help much unless the routine task processes that are being automated are first closely examined and streamlined – applying the principles of “industrialization” and efficiency management to white-collar jobs as blue-collar work was industrialized over 100 years ago.

Without a review and revamping of these underlying processes, any digital banking initiative will fall short of full optimization and, at worst, simply automate already dysfunctional processes.

Bill Heitman is a founder and managing director of The Lab, a management consulting firm in Houston, TX. Bill has been implementing non-technology business improvements for Fortune 500 clients since 1993. He has led strategy development and operations improvement efforts for senior management across major supply chain and services businesses. His views have been published in Fast Company, CFO Magazine, CIO Magazine and the Houston Chronicle. You can also follow Bill on Twitter by clicking here.

Bill Heitman is a founder and managing director of The Lab, a management consulting firm in Houston, TX. Bill has been implementing non-technology business improvements for Fortune 500 clients since 1993. He has led strategy development and operations improvement efforts for senior management across major supply chain and services businesses. His views have been published in Fast Company, CFO Magazine, CIO Magazine and the Houston Chronicle. You can also follow Bill on Twitter by clicking here.