Tom Davenport has long been one of my favorite thinkers/writers in the management space, and his latest piece in the Harvard Business Review, What’s Your Data Strategy?, reminds me why.

Offensive Versus Defensive Data Strategies

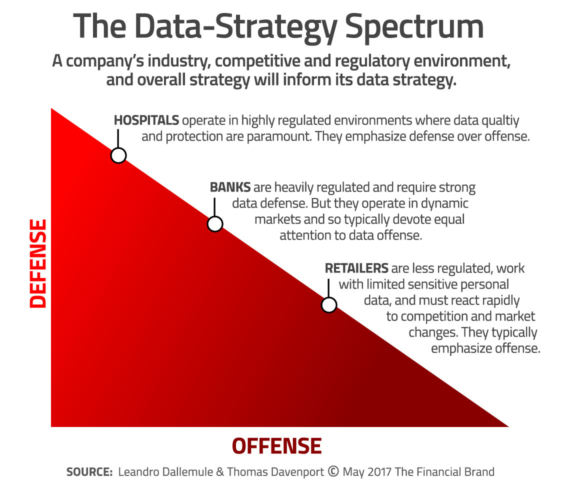

The crux of the article is that organizations “make considered trade-offs between ‘defensive’ and ‘offensive’ uses of data and between control and flexibility in its use.”

Davenport and his co-author describe the differences as follows:

Data defense is about minimizing downside risk. Activities include ensuring compliance with regulations, [and] using analytics to detect and limit fraud. Defensive efforts ensure the integrity of data flowing through a company’s internal systems. Data offense focuses on supporting business objectives such as increasing revenue, profitability, and customer satisfaction. It typically includes activities that generate customer insights or integrate disparate customer and market data to support managerial decision making.”

As the authors point out, on a spectrum of defensive to offensive uses of data, banks fall in the middle, having to play both:

The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th

Explore the big ideas, new innovations and latest trends reshaping banking at The Financial Brand Forum. Will you be there? Don't get left behind.

Read More about The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th

Instant Messaging. Instant Impact.

Connect with your customers and provide lightning-fast support as effortlessly as texting friends. Two-way SMS text messaging is no longer optional.

What are Your Sources of Truth?

Each strategy has its own “enabling architecture.” A defensive strategy is supported by a “single source of truth” while an offensive strategy is supported by “multiple versions of the truth.” What is a “single source of truth”? According to the authors, it’s:

A logical, often virtual and cloud-based repository that contains one authoritative copy of all crucial data, such as customer, supplier, and product details. It must have robust data provenance and governance controls to ensure that the data can be relied on in defensive and offensive activities, and it must use a common language—not one that is specific to a particular business unit or function.

On the other hand, multiple versions of truth result from the:

Business-specific transformation of data into information—data imbued with relevance and purpose. As groups within units or functions transform, label, and report data, they create distinct, controlled versions of the truth that, when queried, yield consistent, customized responses according to the groups’ predetermined requirements.

Beware of Data Truthiness

Overall, Davenport and his co-author provide a great framework for banks and credit unions to approach the development of a data strategy.

But I’m troubled by the “truth” concept.

Academics love to talk about how data can “become” information, and then “turned into” knowledge and wisdom. In the real world, it’s not that clean.

And given today’s political climate, the idea of having “multiple versions of the truth” doesn’t sound like something many organizations would aspire to achieving.

In fact, it seems to me that what most organizations aspire to having is multiple sources of truth supporting a single version of the truth.

Other Considerations for Your Data Strategy

There are elements of a data strategy that weren’t discussed in detail in the HBR article that banks and credit unions should take into account:

1. Data definitions. Another issue I have concerns the impracticality of a “logical, virtual, and cloud-based repository.” That could take a mid-sized bank five or more years to accomplish. “Single source of truth” should refer to data definitions — ensuring a single definition of customer, supplier, product, etc. — not to how the data is stored. You may very well need to change how data is stored, but just consolidating data sources doesn’t produce, by itself, a “single source of truth.”

2. Data ownership. Deciding to step up your organization’s data offense strategy may go nowhere if the data you need to deploy is “owned” by departments in the organization data have a defensive data strategy. Case in point: The folks in risk and fraud management have a lot of data that could potentially be used to benefit marketing. Good luck getting it out of them. Dealing with data ownership issues could very well be the single best reason for having a Chief Data Officer.

3. Data access. Having a single source of truth, and even a consolidated “360 degree of the customer,” could be useless if the right people don’t have access to the data. One large bank I know of went through the data consolidation process only to find that line-of-business marketing personnel had to rely on centralized IT personnel to get data extracts. Marketing campaign execution time went from 2-3 months to 4-6 months. Not good.

4. Data assessment. For all the talk that “banks have all this data but don’t do anything with it” or “Big Data will give us all this new data we’ll be able to use to improve our predictive analytical capabilities” few — if any — banks evaluate the effectiveness of data elements. I’m not talking about data cleanliness. I’m about talking about assessing which data elements truly improve management decision-making.

What’s Your Data Gentrification Strategy?

Davenport’s discussion of defensive versus offensive data strategy is brilliant (typical of his writing). But a bank’s data strategy must go beyond simply focusing on offense versus defense. It needs to focus on the quality of data, and taking actions (i.e., making investments) in data generation, capture, and acquisition if the quality of data falls short of helping the business to improve.

This is why I keep harping on this concept of data gentrification. As I said in The Financial Brand’s Top 10 Retail Banking Trends and Predictions for 2017, “Over the next few years, banking providers will embark on data gentrification efforts — not just cleaning up the data they have, but collecting and using better data.”