Try coming up with synonyms for “banking” or other common industry terms. It’s harder than it seems. That’s why neobanks and other nonbank players often end up using “bank” in some form.

But the newcomers increasingly are running into regulatory pushback as they cross boundaries set in legislation or regulation that established guidelines for the use of bank-related words. (At one time, even bank holding companies couldn’t use the word “bank” in their names, spawning such usages as “bancorporation.”)

It’s not a well-defined area, which explains how nonbanks were able to push the limits for a time. It’s clear that if you claim to offer federally insured deposits that you need to prove that somewhere along the line FDIC is getting your assessment payments. Much else has not been clear.

But some clarity is coming, or, at least, an indication that regulators are thinking more seriously about it.

It’s timely. Bankers, credit union executives and the leaders of fintechs ultimately need an understanding, especially if they are marketers, of who can use the words “bank” or “banking” and when. Fintechs came onstage cloaking themselves in “unbankness,” but they ran into the need to use phrases like “doing my banking.”

“Ultimately, an elemental question is what can a bank do that a nonbank can’t do?” says Adam Shapiro, Partner and Co-Founder at Klaros Group. “Fundamentally, it comes down to a couple of things. Banks can take insured deposits. They can transform maturities, which means they can take demand deposits and make 30-year mortgages with them. And banks can connect directly to the payment system.”

As Shapiro explains it, all of these functions are provided in some fashion by many fintechs and other companies now, but typically through partnership with a bank.

“Calling something a ‘checking account’ implies that you’re a bank, even though it might be a banking as a service arrangement. If you dream up something else to call it, people won’t know what you’re doing.”

— Adam Shapiro, Klaros Group

“But the sands are shifting a bit now,” continues Shapiro, whose long career includes posts at the U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority and BBVA. Two cases, one with a state regulator and the other with the Securities and Exchange Commission, illustrate what Shapiro thinks may be coming.

And it’s not just a U.S. situation.

Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Achieve a better return on your marketing investment. Leverage behavioral data and analytics to target the right customers with the best possible offers.

Read More about Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Are You Ready for a Digital Transformation?

Unlock the potential of your financial institution's digital future with Arriba Advisors. Chart a course for growth, value and superior customer experiences.

Shapiro notes that the U.K.’s FCA in May 2021 issued a letter clarifying permissible usages for e-money firms, which offer digital payment services but which are not full banks.

“We are concerned that many e-money firms compare their services to traditional bank accounts or hold themselves out as an alternative in their financial promotions, but do not adequately disclose the differences in protections between e-money accounts and bank accounts,” FCA wrote.

Historically federal regulators particularly have tended to focus on how well “sponsor banks” in BaaS deals have been monitoring know your customer/anti-money laundering practices and other compliance for the nonbanks offering their services. Shapiro believes the sponsor banks will be expected to do more to watch the overall compliance performance of the nonbanks.

“As some of these players, like Chime, become really big,” says Shapiro, “that is going to change. Over the next couple of years it is quite likely that regulators will ask themselves whether the status quo they’ve accepted for decades is really sufficient.”

Chime ‘Unbanks’ Its Digital Verbiage with Disclosures

Take Chime, commonly labeled as a neobank though it has no charter of its own and the word neobank appears nowhere on its site. For some time its website URL was “www.chimebank.com.” There was logic there, in that consumers come to Chime for banking services and the company uses two bank partners to provide it.

In March 2021, Chime and the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation came to a settlement, including the fintech’s agreement to stop using the URL and to change it to simply “www.chime.com”.

Type in the old address and this is what you’ll see:

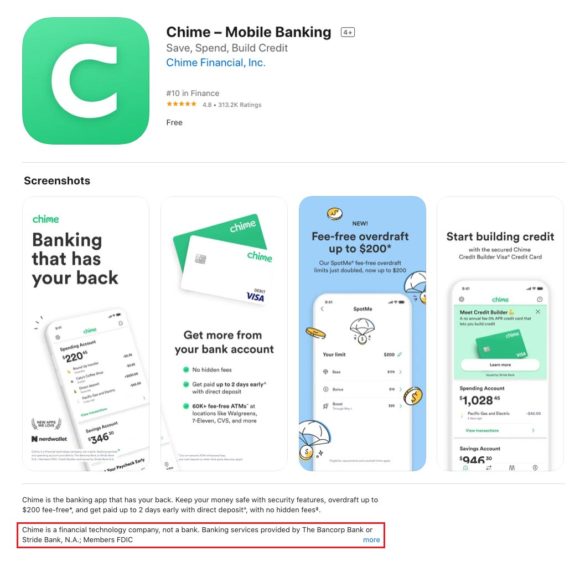

The California regulator’s reasoning was that Chime was not licensed to operate as a bank in the state “or in any other jurisdiction,” and that it wasn’t exempt from licensing requirements. While Chime can use banking terminology in places on its site and app, the company is required to disclose in a significant way that its banking services are provided through its partner banks.

That’s why you’ll see treatments like this app store landing page:

Avoiding the implication that Chime is a bank also applies to items like Chime’s paid Google search results.

Read More: Neobank Tracker: The World’s Biggest Database of Digital-Only Banks

How Coinbase Got Tripped Up by the SEC

As “banking” spreads, so does the regulatory view. In September 2021, the Securities and Exchange Commission sent a “Wells Letter” to Coinbase, a cryptocurrency company. (These documents mean “stop or SEC will sue you.”)

At issue was a service called “Lend.” The service, which did not launch, was designed to allow eligible customers to earn interest on select crypto assets held on Coinbase. Initially this was meant for holdings in USD Coin, a “stablecoin” pegged to the U.S. dollar. SEC has increasingly been going after crypto companies, pursuing the idea that cryptocurrencies are securities subject to regulations on usage and descriptions.

SEC Chairman Gary Gensler, a Biden appointee and former chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, has stepped up the pace on this at the agency, and has been widening SEC’s beam.

Not a Crypto Fan:

SEC Chairman Gary Gensler considers much of the crypto field to be the “Wild West.”

In a Washington Post podcast, Gensler pointed to stablecoins specifically. He said that these “have some attributes of investment contracts, have some attributes of banking products, but the banking authorities right now don’t have the full gamut of what they need.”

Shapiro notes that the SEC has moved in because the banking regulators have no jurisdiction over these activities. What Coinbase was doing blurred the boundary between what is and isn’t banking, he adds.

Read More: 5 Cryptocurrency Issues Banks & Credit Unions Must Tackle Now

How Added Attention to BaaS Deals Could Begin

There are several different ways federal regulators could begin paying greater attention to the use of “bankness” by nonbanks, according to Shapiro.

One avenue is the power federal banking regulators have to examine any “institution-affiliated party.” After such examination, the agencies are permitted to pursue enforcement actions.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has enforcement powers that could be applied. One potential authority that could be tapped is its “UDAAP” jurisdiction — that is, the ability to go after “unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts or practices.” Shapiro explains that CFPB doesn’t have supervision authority over BaaS programs but could pursue enforcement actions against one if they find marketing or other efforts to be misleading or harmful to consumers.

Shapiro suspects the pace of such activity will hinge on the future for nonbanks’ ability to obtain banking charters. He notes that Varo’s becoming a full-service national bank with its own charter took a long time, but it finally happened. (In addition some have taken advantage of state industrial bank charters.)

The Biden administration has yet to make its policy clear on charters for such players, though signals from Acting Comptroller Michael Hsu haven’t suggested any liberalization of past practice — actually, more likely the opposite.

“It’s not that the door has slammed shut,” says Shapiro, “but the opening has somewhat narrowed.”

He adds: “Regulators do not like shadow banking, where an activity is only indirectly in the banking system, or outside of it totally. And yet it seems like over the last six months, the path for people who want to come out of the shadows and be directly regulated and play by the rules has become a lot more uncertain.”