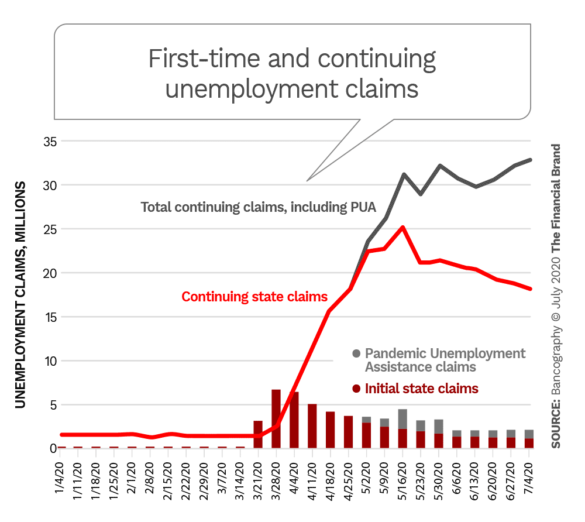

The emergence of the COVID-19 crisis and the ensuing economic lockdowns produced record levels of unemployment, with 50 million state-level, first-time unemployment claims filed in the 16-week period beginning on March 21. State-level claims still exceeded 1.3 million per week as of early July, or double the peak level during the financial crisis of 2008-09.

Further, almost all of the nation’s job growth in May and June resulted from the recall of temporarily furloughed employees, even as permanent job losses actually increased in each of those months.

However, in contrast to 2008-09, several of the primary economic indicators, most notably housing sales, home prices, and consumer spending, remain seemingly unscathed. How is it that these key economic indicators have remained so resilient in this recession?

Most notably, the lockdown has disproportionately impacted the retail and services sectors where wage bases skew lower. To date, this has remained largely a blue-collar recession, with higher-earning (and thus higher-spending) white-collar employees continuing at work, often from home.

Also, governmental programs of two types manifested immediate benefits. One-time stimulus checks and expanded unemployment insurance yielded an increase in aggregate U.S. personal income of 10.5% in April versus March; and even after a 4% decline in May, aggregate personal income still remained above pre-pandemic levels. Concurrently, the Paycheck Protection Program of the federal CARES Act helped millions of businesses retain employees on payroll, preventing unemployment levels from soaring even further.

Beyond those direct payments to consumers and businesses, an array of federal mortgage forbearance programs and state/local eviction moratoriums prevented immediate-term foreclosures and evictions of those who suffered income declines, protecting housing prices. A lack of inventory from homeowners reticent to enter the home-showing process in the midst of a pandemic has also helped keep home prices elevated. In addition, the housing market benefitted from lesser leverage today than in the 2008-09 crisis: Home equity line and loan use has declined by nearly 50% since mid-2009, and equity ratios have increased substantially.

With these support mechanisms, the nation may have averted a depression, but numerous warning signs remain for a sustained recession.

Are You Ready for a Digital Transformation?

Unlock the potential of your financial institution's digital future with Arriba Advisors. Chart a course for growth, value and superior customer experiences.

Why Industry Cloud for Banking?

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking helps deliver personalized products and services that today’s customers expect.

The Shape of a Recovery Won’t be a ‘V’ or a ‘U’

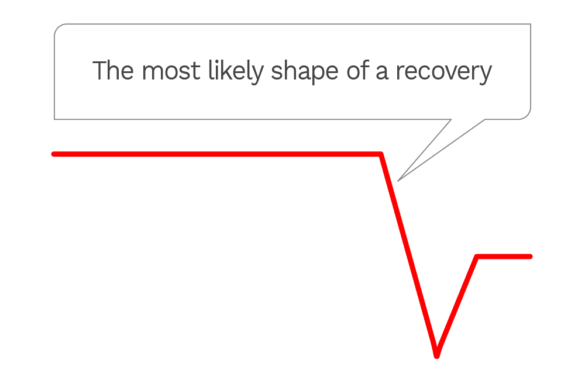

There have been countless articles debating the ‘letter shape’ of eventual recovery. For example, the V-shaped recovery would occur with a quick and sharp bounce back to pre-pandemic levels; the U-shaped recovery would involve a more gradual ascent to prior levels; and a W-shaped recovery could experience some level of backsliding after an initial rebound, prior to full recovery.

However, the most likely and unfortunately troubling scenario may most closely resemble a distorted version of the square root symbol, with the ‘long’ and ‘short’ sides reversed. That is, we may see demand initially rebound in a shape indicative of a ‘V’, but then plateau at some level below pre-pandemic pace; and this would imply treacherous conditions over the next six months.

Absent a COVID-19 vaccine, several factors will continue to create substantial headwinds for the economy and financial institutions.

Foremost, at some point the support payments and forbearance/eviction-moratoriums will winnow or expire completely. Though uncertain at present, an additional round of federal support may be forthcoming, but likely at a lesser income-replenishment level than in the initial wave of relief measures. Already there is some evidence of firms indicating layoffs immediately following exhaustion of PPP funds. Note also that commercial bankruptcy filings increased by 26% in the first six months, and any continuation of that trend will bring added layoffs, too.

A sharp decline in oil prices will continue to drag on employment and investment in the important energy sector. Further, consumer reticence to travel and dine out will continue to impair the hospitality sector that employs 10% of U.S. workers.

In concert, these and other economic hardships will ensure unemployment remains well above pre-pandemic levels; and coupled with the expiration of income-support and forbearance programs, will likely accelerate consumer defaults and erode home prices.

“Many ‘second-order’ impacts will migrate up the wage ladder, bringing more permanent white-collar job losses, versus the sometimes-temporary, blue-collar service sector furloughs.”

Continued economic slowdowns will bring second-order impacts, too. For example: The downtown restaurant that loses traffic as some portion of the workforce remains on work-from-home status; the stores in a college town where only a proportion of students and faculty return to campus; the accounting firm with fewer clients as companies vanish. All will suffer revenue losses, sometimes at lethal levels. And notably, many of these second-order impacts will migrate up the wage ladder, bringing more permanent white-collar job losses, versus the sometimes-temporary, blue-collar service sector furloughs.

Even if consumer spending revives to 90% of pre-pandemic levels, how many firms can withstand a 10% revenue loss? In many cases, a 10% reduction in revenue creates a 60% reduction in profits due to the impact of fixed costs and the fact that only the last marginal sales create profits sufficient to offset those fixed costs.

Finally, consider that as the second-order effects ensnare more higher-earning, white-collar employees, more businesses will suffer as even top-tier clients reduce visits, underscoring how little margin there is for even a modest decline in sales activity.

In sum, a recovery in the ‘distorted-square-root’ shape described above would herald an acutely troubled economy.

Bank Balance Sheets Will be Squeezed

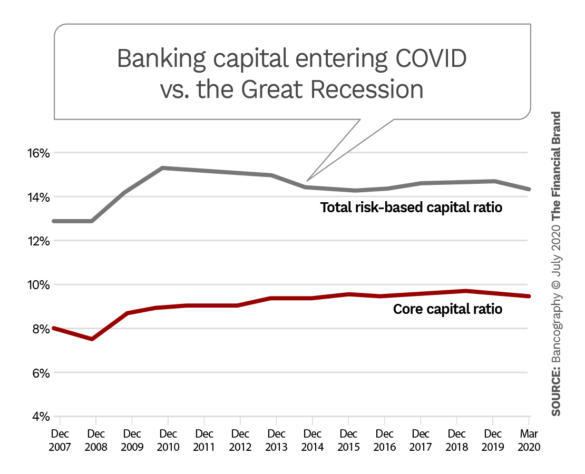

In the early stages of the pandemic bank balance sheets remained robust and healthy, but fraught with harbingers of trouble ahead.

To the positive, the banking industry entered the COVID-19 crisis in a much stronger position than it entered the 2008-09 financial crisis due to a raft of regulatory actions that emerged from the earlier crisis.

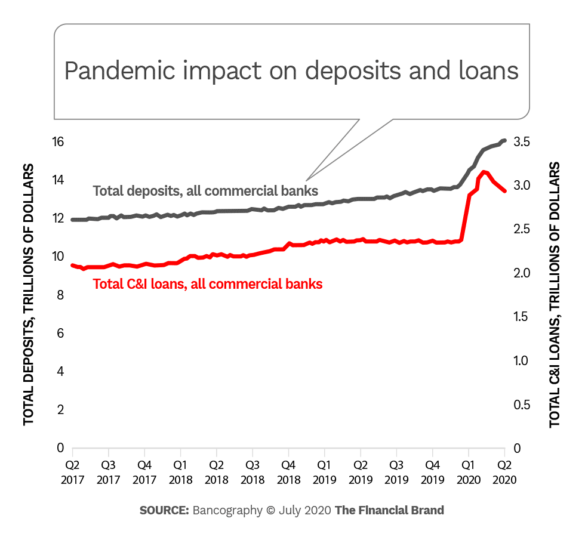

In another positive, the industry enjoys ample liquidity with deposit balances soaring due to inflows from federal stimulus programs and consumers’ reticence to spend in an uncertain economy. Between March 30 and June 15, total deposits in U.S. banks increased from $13.5 trillion to $15.5 trillion, as businesses deposited the proceeds of PPP loans and consumers deposited stimulus checks and enhanced unemployment benefits. Many businesses simply parked the PPP proceeds in their checking accounts.

Similarly, many consumers saved rather than spent stimulus funds. Finally, note both business and consumer spending declined not only because of economic uncertainty, but also for the simple reality of having fewer places to spend.

Outlook for Loan Portfolios

High levels of deposits will inevitably erode as income support measures wane; and concurrently, troubles will heighten on the asset side of the balance sheet. On the commercial side, commercial and industrial loans showed a jump, mirroring the business deposit inflow, as PPP borrowings elevated aggregate bank C&I loans from $2.4 trillion in mid-March to $3.1 trillion in early-May. However, by the end of June, that total had regressed to $2.9 trillion, likely reflecting the pay down of existing loans with limited replenishment in an economy with fewer firms seeking to borrow for immediate expansion or operations.

As the PPP loans convert to grants and roll off of banks’ balance sheets, the lack of traditional C&I demand will threaten earnings levels.

Commercial real estate loan volumes appear to have plateaued in June. More concerning, delinquency rates in CRE loans had increased to 82 basis points at the end of the first quarter, after hovering near 68 bps in each of the prior three quarters. In one indicator of second-quarter performance, bond-rating firm Fitch reported delinquencies within commercial-mortgage-backed securities instruments rising from 1.46% in May to 3.59% in June — the largest one-month increase on record. The firm projects the delinquency rate to peak near 8.5% in the third quarter, a harrowing harbinger for banks’ on-balance sheet CRE portfolios (and possibly for their investment portfolios).

“Of mortgage loans in forbearance, 46% had a payment made (partial or full) in April, but only 24% had one in June.”

On the consumer side, data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey and mortgage-software provider Black Knight showed that as of early July, 8.5% of U.S. mortgage holders had enlisted in some type of forbearance program. Of those loans in forbearance, 46% made a payment (partial or full) in April, but only 30% did so in May and 24% in June, suggesting increasing financial hardship as the lift from stimulus checks fades. Although most institutions sell forward the vast majority of mortgages they originate, many legacy thrifts and credit unions still carry sizable mortgage portfolios, and many other banks retain some proportion of originated mortgages.

The earliest crisis impacts may be reflected in an increase in nonperforming loans, which accelerated from a total of $83 billion across all U.S. banks as of December 31, 2019 to $88 billion as of March 31. But bankers clearly anticipate further challenges, as the industry’s aggregate allowance for loan losses grew from $113 billion as of March 31 to $152 billion as of June 30.

Absent an extension of fiscal stimuli or a marked, rapid recovery in the employment market, the expiration of income support, mortgage forbearance, and rent-deferral programs will tax consumer finances, not only accelerating credit losses but also hampering consumer spending to a degree that will further pressure business viability. Thus, we should anticipate reduced earnings; and though bankers can to some extent accelerate the recovery by keeping credit (prudently) available, in the near term the industry will remain constrained by macroeconomic trends.

The Pandemic Impact on Branch Networks

Whenever banks and credit unions face earnings challenges, the branch network emerges as an obvious target for expense reduction. At typical retail-driven institutions, branch operations account for about two-thirds of total noninterest expenses. The forced closing of branch lobbies during the pandemic, driving consumers into other channels, has raised a question of whether institutions need to reopen all their branches.

In assessing this, first keep in mind the fundamental role of the branch is not as a transaction processer; that is simply a cost banks and credit unions absorb for the convenience of account-holders. Rather, the branch exists to add new accounts and to ensure bankers meet clients’ continually evolving needs with the appropriate products and services throughout their lives. In this role, the personal interaction that branches deliver can provide both value and differentiation, especially for smaller institutions.

Still, earnings constraints may demand cost reductions, and if so, the top consideration should be to consolidate around existing strongholds. This would include paring one-off forays into markets where the franchise lacks the critical mass to leverage the network effect Correspondingly, it also implies maintaining branch depth in areas where the institution already enjoys a strong incumbent position.

Further economies may lie in converting from a traditional operating model, where every branch functions essentially as a miniature bank unto itself; to a hub-and-spoke model, where only certain functions are delivered by on-site personnel at every branch, while other functions migrate to centralized delivery at the hub.

“If consumers have adopted to reduced branch availability, that could allow migration to a model where electronic channels assume the role of spoke branches. … The surviving hubs [would then] become essential representations of the institution’s brand.”

If those actions cannot deliver sufficient expense reductions, an institution may need to consider in-market consolidations. And while incremental branch contraction represents the most risk-averse approach, any evidence that the pandemic has permanently shifted consumer preferences to remote channels could allow more radical configuration. If bankers believe consumers have adopted to reduced branch availability, that could allow migration to a model where electronic channels assume the role of spoke branches.

Inherent in this approach though, is that the surviving hubs, the flagships, become essential representations of the institution’s brand; meriting investment in interior and exterior design and merchandising. However, if widespread branch closures occur without offsetting investment in surviving branches, consumers may (rightfully) perceive a distressed institution focused more on survival than client needs, accelerating the institution’s decline.

Even with profitability challenges forcing an examination of expenses, stronger banks and credit unions may still want to consider expansion opportunistically. The commercial real estate issues discussed in the prior section should reduce land and lease prices for new branches.

Although there is a defensible viewpoint that the crisis will precipitate acute permanent declines in branch transaction levels, a counterargument could posit that the early adopters of electronic channels exited the branch channel long ago, and the remaining mixed-channel and branch-dependent users will drift back as lobby availability returns.

As such, bankers should prepare business cases for various points along the continuum spanning from “current depressed activity levels turn permanent” to “everything reverts to prior state.” As long-term trends emerge, they can then pursue the appropriate tactics in reconfiguring branch networks. But in the immediate term, all bankers should be considering opportunities to increase branch network operating efficiency, to offset near certain declines in revenue and increases in credit losses as the recession drags onward.