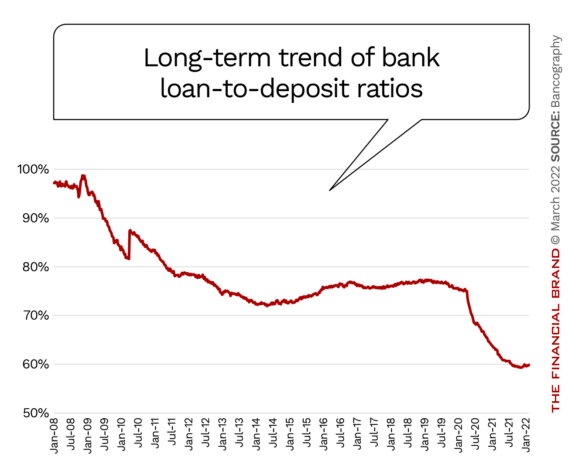

More changes now occur in banking in a year’s time than used to occur in the typical banker’s career. Who would have predicted even just 12 months ago, for example, that one big bank after another would do away with overdraft fees? Or that the industry’s loan-to-deposit ratio would be down around 60%, with deposits still piled deep on the balance sheet?

These and many other challenges face banks and credit unions now competing not only with each other but with an ever-growing list of nonbank companies. But as always change also brings opportunity.

In its annual banking industry outlook, research and consulting firm Bancography provides a detailed review of key industry trends including deposits, lending and branching along with economic and demographic data.

The 52-page report, crammed with charts, also analyzes the often conflicting signals presented by the data. This article summarizes the key trends and challenges identified by the report, and offers additional insights based on an interview with Bancography’s President, Steven Reider.

1. Deposits Remain at Historically High Levels

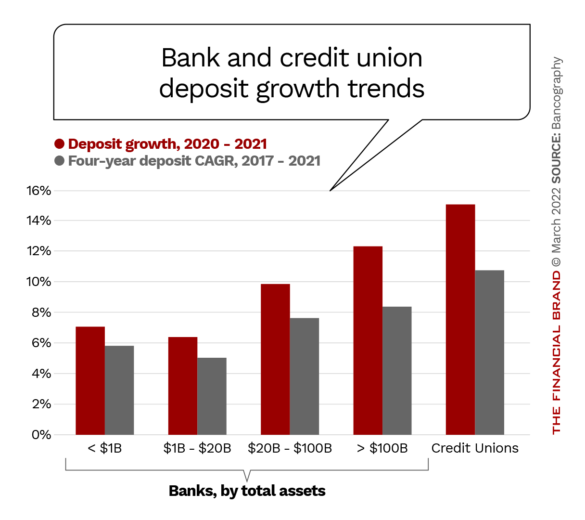

Retail and small business deposits grew a massive 12% year-over-year in 2021, the report states. While that was actually down from 2020’s 20%+ number, it was still three times above historic norms. “Every top 30 market except San Francisco, Pittsburgh and New York City posted at least 10% deposit growth — stratospheric levels compared to the norm,” the report notes. Top markets were Atlanta, St. Louis and Tampa.

Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Achieve a better return on your marketing investment. Leverage behavioral data and analytics to target the right customers with the best possible offers.

Read More about Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th

Explore the big ideas, new innovations and latest trends reshaping banking at The Financial Brand Forum. Will you be there? Don't get left behind.

Read More about The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th

The reasons for the continued above-normal deposit inflows were a repeat of the previous year: federal Covid relief programs, lack of consumer spending (at least initially), and businesses reluctant to invest. “All that adds up to deposits piling up into bank accounts of consumers and businesses alike,” says Reider.

He predicts a reversion to historic norms over the next two years, however — beginning in 2022 — as consumers burn off some of the surplus and businesses invest more. True, high inflation will erode wage gains and cause spending to decline and people to tap savings to cover higher expenses. But that could also bring a positive, the report notes, by reducing banks’ interest expense as savings are drawn down from very high levels.

Among banks, the largest institutions enjoyed the biggest deposit gains, as they have for several years. However, credit unions grew more deposits on a percentage basis. Reider gives two reasons: 1. They’re increasing from a smaller base, and 2. the lending sectors in which most credit unions participate — indirect auto loans and home mortgages — were the most active. That meant many credit unions were actively seeking deposits.

Read More: 2022 Trends Reflect a New Era for Banking

The industry overall entered 2022 still carrying excess liquidity, with loan-to-deposit ratios barely hitting 60% at the start of the year.

Bancography sees solid prospects for loan growth in 2022, despite rate hikes. “A 50 or 100 basis point increase would leave borrowing rates well below historic norms,” the report states. That leads to two key lending opportunities.

2. Credit Cards & Home Equity: Down, But Not Out

The biggest cause of banking’s excess liquidity on the loan side was the falloff in credit card lending, Reider notes. That decline prompted much speculation as to whether the rise of alternative payment products like Venmo and Zelle or buy now, pay later plans have pushed credit cards into early retirement.

Reider doesn’t see it that way. He predicts cards will bounce back from their pandemic lows. “The data show they’ve bottomed out,” he asserts. Also, consider that the sectors most impacted by the pandemic — travel, leisure, hospitality — are very credit card dependent. Reider believes the expected draw-down in consumer liquidity plus an uptick in travel and other card-dependent sectors should boost credit card demand.

Read More: The Future of Consumer Credit in 2022 (And Beyond)

As for alternative payments, they only work “if you have a liquidity cushion,” he points out. Without liquidity, the credit card becomes “a tool not just of convenience, but of income extension and rearranging your payments timing.”

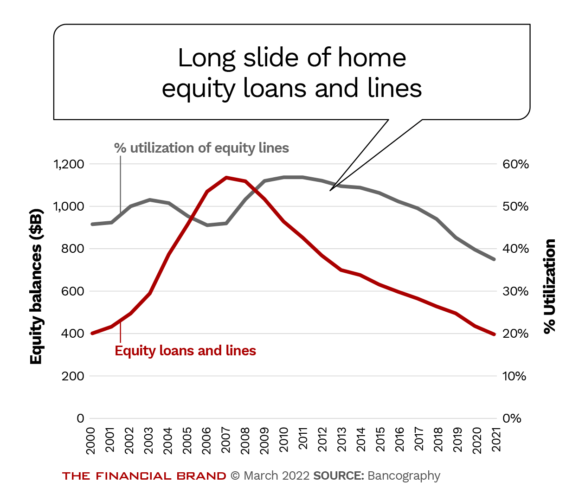

Reider is also bullish on another credit product that has been on the ropes for several years: home equity loans and home equity lines of credit. Indeed, the chart below would seem to depict a product well past its prime.

“We’ve seen more than half a trillion dollars in home equity balances erode since the Great Financial Crisis,” Reider acknowledges. “At some point, however, I think we’ll see that turn around. A few factors right now favor home equity borrowing in a way that hasn’t been seen for ten years.”

The consultant ticks off several: The combination of rising rates, higher tax rates in the uppermost brackets, and, of course, the soaring equity that consumers carry in their homes. All of that may be finally revive that product, which Reider believes is important for banks.

The Case for HELOCs:

Home equity lines are a good way to lock down emerging affluent households that have high income but not necessarily a lot of liquidity.

“If banks can get home equity products going again,” says Reider, “it will bring great cross-sell opportunities for money market accounts and checking. Banks would be wise to reemphasize the home equity product.”

3. Finding New Sources of Fee Income

The Bancography report spells out the unfolding overdraft fee challenge quite clearly: “Banks and credit unions alike that are still maintaining current fee structures will face immense competitive pressure… given the visibility of the initial large-bank announcements and the irrefutably consumer-friendly nature of the changes.”

In his interview with The Financial Brand, Reider says when institutions “face something like this — call it ‘socially responsible banking’ — it becomes pretty untenable not to follow, once other institutions have led.”

Since overdraft/NSF revenue is a huge percentage of their noninterest income, and because they don’t have big commercial loan origination fees or trust or underwriting fees like the largest banks do, community financial institutions need to find other “fee streams,” says Reider.

The Bancography report points to wealth management, insurance sales and investment advisory business as logical options for community and regional banks and credit unions to replace lost fee income. Most of these businesses haven’t caught on in a big way previously.

Insurance sales in particular, strikes Reider as a natural cross-sell opportunity for banks, and quite a few community banks have bought small insurance agencies over the years. “I think interest in insurance is going to perk up now,” Reider adds.

The report adds that such advice-driven business lines are better presented in-person at a branch, which could help offset the declining use of branches for basic transactions.

4. Branches Moving to a ‘Hub and Hub’ Strategy?

“With electronic channels now addressing a large proportion of simple and routine transactions, the frequency of branch visits among mixed-channel users will likely decline, leaving only a diminishing pool of branch-only customers with their behavior unchanged,” the report states.

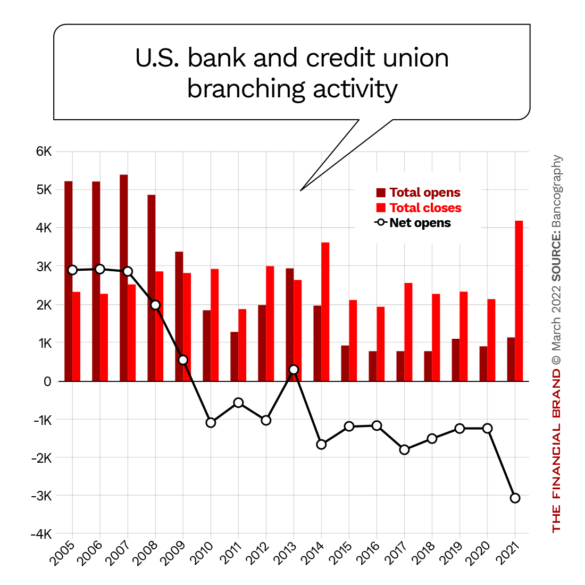

That is one of the reasons for the massive branch contraction seen in 2021 — a net decline of 3,100 bank and credit union branches.

These closures have yielded a less-concentrated branch landscape, Bancography states. Across the U.S., there is now one branch for every 1,240 households, compared to one for every 1,060 households in 2015.

Read More: Why Bankers Won’t Ditch Branches, Despite Digital’s Explosive Growth

In such an evolving environment, bankers have several options. One is to remove certain functions — such as commercial banking, mortgage lending, wealth management — from what Bancography calls “in-between branches,” opting instead to deliver those services from nearby offices in the familiar “hub-and-spoke” model.

Worth Considering:

Pre-pandemic, a downtown hub branch would have been an imperative, but reduced city workforces may have changed that. And the opposite could now be the case in many suburbs.

But the report raises an interesting question: “If the spokes serve purely simple activities, and electronic channels can supplant those, can the institution renounce those branches entirely, retrenching to a ‘hub-and-hub’ model?” In other words, reverting to only primary branches in significant markets with greater space between branches.

As Reider observes, it’s similar in concept to the difference between visiting a grocery store every week versus the doctor’s office once a year. People want the grocery store to be close by, but are willing to travel further for an occasional visit.

“But,” he cautions, “if you go with that hub-and-hub model and you don’t have other means to build your brand — the way Chase, Capital One and Bank of America do —then you better be sure those surviving branches make a statement. They’ve got to be ‘super hubs,’ or flagship branches, that really have some size and branding heft to them.”

An exception to the above, says Reider, are institutions with branches in widely spaced rural communities. “For many community banks ‘community’ is not just a proxy for size,” he observes, “they very much believe that local community presence is part of their mission.” For such banks, he says, “there’s not a real opportunity to get out of a community.”