Even as the debate continues over when, how and how quickly America can reopen for business, the question on everyone’s mind is “What will the ‘new normal’ look like?”

That question looms large in banking, as banks and credit unions attempt to serve consumers and businesses as much as possible digitally, with branches providing drive-through service for the most part, with some lobby service available by appointment.

Predictions abound that COVID-19 should be carved on the tombstone of branching, because it spells the end of branches.

Jean-Pierre Lacroix, President and Founder of Shikatani Lacroix Design, has been involved in banking and retail branch design for many years. His firm also recently completely a study of thousands of American and Canadian banking customers to determine how they feel about branches post-pandemic, and he’s researched the surrounding trends.

His response to the predictions is two-fold.

First, branches are not going away. How they are used by consumers and businesses (and by bank and credit union staff) will change. That reflects a combination of changing attitudes due to COVID-19 worries, evolution already underway, and the adoption of digital channels by many who had never used them before.

How they are set up, designed and operated will also change, in some cases significantly.

Second — and of far more concern — is something sure to send bankers and credit union executives to their painkiller of choice.

“The reality is that this disease, COVID-19, is just one pandemic,” says Lacroix. “We’re going to see more of these. This is just the beginning. This is training. We have to get used to it, because more is coming.”

An exaggeration? Don’t be too fast to assume so. Lacroix reels off 15 years or so of diseases that many of us might have considered isolated instances. SARs, H1N1 (swine flu), bird flu, West Nile and Zika are among them. He makes a persuasive case that most of us missed the signs of what was coming.

“You’re going to have a population that is very, very aware of the risks, so institutions will have to build anti-virus environments within the branch experience to be more permanent,” says Lacroix. Even after things return to “normal,” he continues, “there is always going to be some residual anxiety. The more vulnerable you are to the virus, the more you’re going to be concerned about going back into a public place like a bank branch.”

Lacroix also warns that as financial institutions further refine their offices for a post-COVID-19 world, going more and more digital and remote, they will expose a new risk to their own existence. But let’s examine post-COVID-19 branch issues first.

Why Industry Cloud for Banking?

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking helps deliver personalized products and services that today’s customers expect.

Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

83% of FI leaders agree investing in AI is essential for 2024 but how you leverage AI is instrumental in success and meeting customer expectations.

Read More about Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

Here’s Why You’re Going to Reopen Your Branches

The firm’s report, “Retail Banking’s New Reality: Responding to the COVID-19 Crisis,” is based on input from about 2,000 consumers. There is no indication in the report that consumers plan to avoid branches completely. Instead, as the study shows in detail, they chiefly want to see clear and extensive efforts to contain any risks going forward. Even if elimination of branches were the goal, it’s not likely to occur soon.

Here’s why Lacroix doesn’t see branches going away.

“The physical channel remains the way to capture new retail customers.”

— Jean-Pierre Lacroix, Shikatani Lacroix Design

First, “the physical channel remains the way to capture new retail customers,” he insists. He points out that even in markets like Ireland, where less than 5% of transactions occur in branches, the banking industry still maintains branch networks as a tool for growing market share.

Second, Lacroix praises the industry, overall, for investing so much in digital channels. Had that not been the case, he suggests, there could have been bank runs as people attempted to maximize their cash as branches curtailed service. Much has been possible because those channels existed.

Changes will be necessary, but Lacroix describes a three-tier prioritization that he’s convinced the industry will impose on its branch networks.

• The first is in congested markets like New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, Atlanta and Detroit.

“That’s where the pandemic has scarred the social fabric of the community and it won’t heal,” says Lacroix. “So in such markets you are looking at a permanent model for social distancing and sanitization.” In markets like that, expect major retrofits, including using special materials for surfaces often touched, in order to give a potential resurgence of coronavirus no place to grow and spread.

• The second is a middle ground of markets and branches where traffic and population are high enough that some changes and some adjustments to processes and procedures are warranted.

There an institution would need to be very visible in exercising caution over too many people assembling, mandating social distancing and including safeguards such as masks and gloves for staff. In some cases more than the basics will be necessary initially, he suggests, “so you need to create systems that you can put in place but later flip back to normal again.”

• The third tier, in Lacroix’ view, could display a minimum of changes, almost “business as [old] usual,” and not have trouble.

This would occur in markets where COVID-19 had little or even no impact. To denizens of locked-down urban centers this may seem impossible but he says there are rural pockets where no one travels and no sign of the illness has arisen. His firm also works with restaurants and in a study of that industry it found that about 17% of food service operators have had little or no impact from COVID-19.

What Will Make Consumers Confident that Branches Are Safe Again?

Now, in an age of social distancing, banks and credit unions face an apparent twist in history. For decades they have been shrinking the footprint of branches. Suddenly, it would seem, they are going to be putting too many people in too small a space.

But that’s not actually right, according to Lacroix. “It’s not so much a matter of space, but a matter of separation,” he explains. “It’s a matter of having someone sneezing or coughing and making sure none of those particles fall on you.”

Instead of increasing space, institutions will take steps to control traffic in physical ways and digital ways, and will make multiple changes in branch layout and practices. In some ways it will be much as Americans have been seeing in supermarkets all through the coronavirus pandemic —controlled access to the branch, marked-out zones for standing in line, plexiglass barriers between the public and tellers and universal bankers, and more. But the effort at banks and credit unions will become much more sophisticated, where it is warranted.

“Somebody coming into the branch has to have a level of confidence that it is a safe haven for them.”

Overall visibility and communication of what the financial institution is doing will be imperative to make it clear that it is taking the public’s health concerns seriously.

“Everything needs to be articulated,” says Lacroix. “Somebody coming into the branch has to have a level of confidence that it is a safe haven for them.”

Institutions will have to go beyond what the public sees, however, to maximize safety. While stripes or circles on the floor put there to separate people are obvious, for example, many may not be thinking of the air they are breathing in the branch.

Six months ago, who did?

But the institution must do so now, because ventilation systems move air in mass quantities. New construction will likely require state-of-the-art systems, and Lacroix says that existing heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems will have to be fitted with filters that will remove potential contagion from the air.

“Think of it as some of the strategies that used to be used to overcome people smoking in buildings,” Lacroix says. “It’s a similar challenge.”

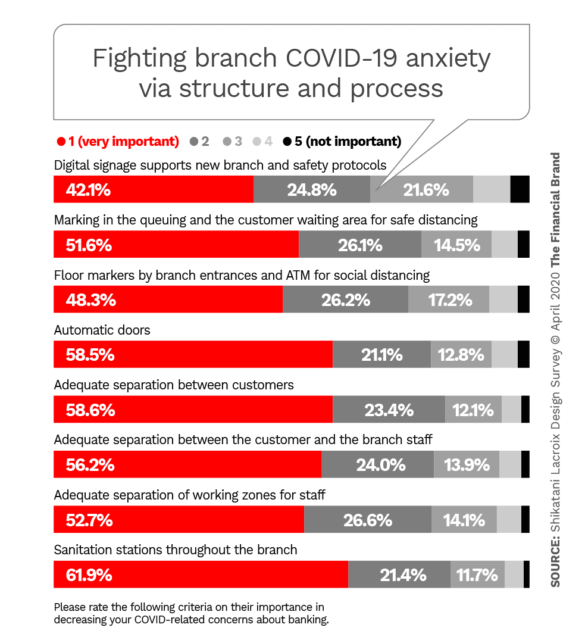

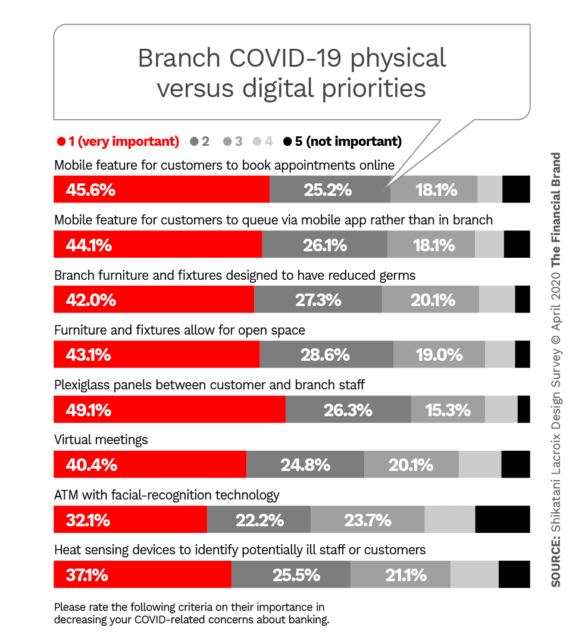

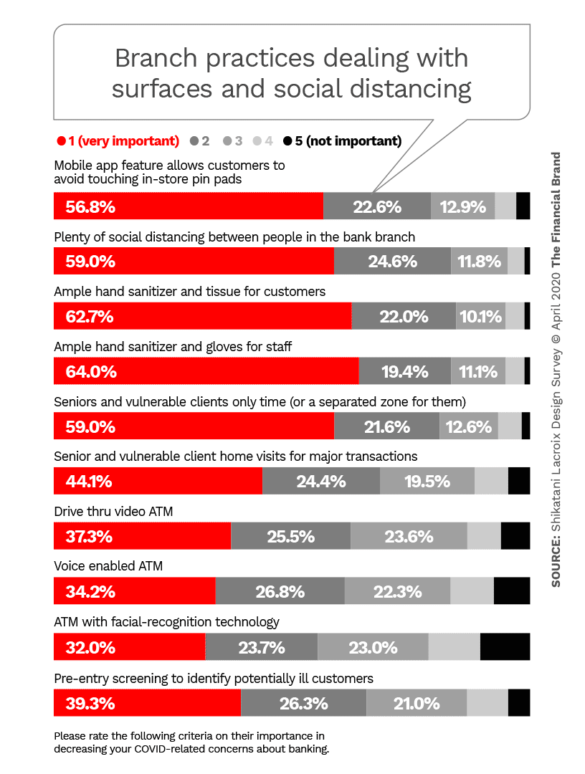

(The three charts in this section detail the preferences of the public in three broad areas, based on the Shikatani Lacroix Design study.)

Branch meeting rooms will need to be reconsidered, both in their purpose and their size and layout, says Lacroix. “It’s a close environment normally,” he says, “so you have to start thinking about how many people can be in a room, how far apart they need to be, and whether the meeting couldn’t be handled virtually. I think videoconferencing is going to take on a whole new level of use in institutions that haven’t used it before.”

Floor plans must be reconsidered and the materials used in countertops, chairs, and more must be weighed.

Employees are another dimension. Their own use of gloves, masks, hand sanitizer and their visible practices need to be considered, both for the impression it makes on the public and practical purposes.

“What’s going to be your protocol if someone is sick?” asks Lacroix.

A key issue that many American banks have resisted up until now is electronic queuing of branch visitors, in order to control the number of people in the office at any given time. It’s not rocket science — Apple Stores has long mandated that consumers make appointments to get help at the Genius Bar, for example, and Disney has controlled traffic through multiple generations of its Fast Passes for years. Multiple vendors sell systems to make queuing practical.

Video meetings between staff and consumers and business people will replace many of the in-branch meetings that are a staple of banking, according to Lacroix. Even so, some groups of customers, such as the elderly, startups, and small business owners will from time to time want a true face-to-face meeting.

One surprise to Lacroix in the findings was that through the COVID-19 period there has been strong use of telephones, both through interactive voice response systems and live calls with staff at various level. Notably, a great deal of the latter has been to obtain live help in figuring out how to use institutions’ digital banking tools, especially for complete newcomers.

What Happens as the Tipping Point to Digital Comes?

Lacroix draws on both the current survey as well as earlier research in a warning to retail bankers about the impact of the changing role of the branch. As people of all ages gravitate increasingly to digital channels, they can become more mobile — not just in the sense of their phones, but the possibility that they will change their primary financial institution.

The current study found that while the percentage of respondents who say they are highly likely or likely to move once the pandemic is over is relatively small (8.9%), but 17% is undecided. The report notes that the undecideds as a group are skewed towards consumers traditionally likely to use branches.

“What this implies is that any physical branch precautions now will have a steep impact on the brank’s perception once COVID-19 is over,” the report states. “This means physical banks must be ahead of the curve in precautionary action now to reassure their customers and gain those who are dissatisfied with their own banks.”

That will secure those who still strongly favor branches. But Lacroix suggests other steps may be necessary to hold onto those who were forced to try digital and who have come to prefer it. In an earlier study the firm found out that once they’ve cut or loosened the umbilical to branches, people will look further afield for banking relationships.

“That was already happening,” he says, “and now we’re just accelerating the process.”