The rise of electronic transaction channels has raised fundamental questions about the role of traditional branches. As consumer preferences evolve and new channels emerge, bankers must consider how the branches fit into their distribution networks. In this extensive, must-read briefing on branches, Bancography tackles everything from transaction declines and network sizes to consumer preferences and cross-selling.

This briefing from Bancography examines the state of branch banking in the U.S., trends in branch activity, and the impact of new technologies to assess the role of the branch in an age of rising electronic channel availability. The bottom line? Branches remain the predominant channel for new account sales, and location convenience remains paramount in institution selection.

This briefing from Bancography examines the state of branch banking in the U.S., trends in branch activity, and the impact of new technologies to assess the role of the branch in an age of rising electronic channel availability. The bottom line? Branches remain the predominant channel for new account sales, and location convenience remains paramount in institution selection.

Financial institutions shouldn’t view the migration of transactions to electronic channels as a threat to branches, but rather as an opportunity to reorient them toward higher-value sales activities. The combination of reduced staff requirements and new technologies makes smaller, less expensive branches a reality, yielding more viable locations for expansion, which in turn provides consumers with the convenient access they want.

The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th

Explore the big ideas, new innovations and latest trends reshaping banking at The Financial Brand Forum. Will you be there? Don't get left behind.

Read More about The Financial Brand Forum Kicks Off May 20th

Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

83% of FI leaders agree investing in AI is essential for 2024 but how you leverage AI is instrumental in success and meeting customer expectations.

Read More about Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

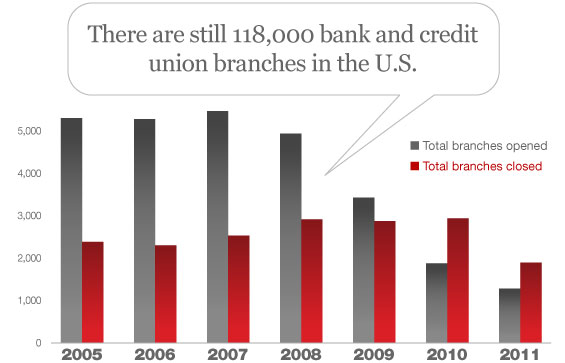

Are Branch Networks Really Shrinking?

“There are still 118,000 bank and credit union branches in the U.S. now, or roughly one branch for every 1,000 households in the nation.”

The middle part of the last decade saw unprecedented levels of branch construction. Banks and credit unions built more than 5,000 new branches per year in 2005, 2006 and 2007, with branch inventories increasing by 3,000 units (net of closures) in each of those years. Although the pace of construction slowed significantly during the economic downturn, there are still 118,000 bank and credit union branches in the U.S. now, or roughly one branch for every 1,000 households in the nation.

After many years of increases, branch closures outpaced branch openings in 2010 and 2011, and the total inventory of branches has declined by about 1,600 units from its 2009 peak. The reality is that the overwhelming majority of those reductions were merger related. Indeed half of the net 1,600 unit decline arose from just two institutions — Wells Fargo and Bank of America — and 80% of the net decline in branch inventory was impounded in just eight of the country’s biggest banks (including PNC, BB&T, BBVA Compass and M&T Bank).

Even in the face of one of the worst economic environments of the last 50 years, more institutions added to their networks than reduced. In the FDIC reporting year that ended on June 30, 2011, 480 banks had added branches, versus only 418 that reduced their networks. Of course, this indicates that the vast majority of the nation’s 7,500 banks left their branch networks unchanged.

Heavy Competition Results in ‘Prisoners Dilemma’

The performance of recently opened branches has been modest. Of all the branches opened in 2004 through 2006 (i.e., the group of branches that have five years of FDIC deposit reporting history), the median deposits for traditional branches (excluding in-store locations) on their fifth anniversary was only $19 million. And only 17% of new branches exceeded $40 million in deposits after five years. This compares to a median of $38 million in deposits for mature branches (defined as those opened for more than five years), and more importantly, falls acutely below the $35-$50 million five-year range most bank CFOs typically demand from branch capital investments.

While branch opens reached record levels in the prior decade, the results of those opens remained modest, at least in part because multiple institutions targeted the same intersections. In doing so, financial institutions diluted the forecasted demand to untenable levels. This phenomenon, akin to the “Prisoner’s Dilemma” from the game theory discipline of economic research, holds significant implications for new branch construction formats that will be discussed later in this briefing.

Branch Transactions Plummet 25% in 5 Years

“Across the industry, median branch transaction counts have declined to 7,600 transactions per month, compared to over 10,000 five years ago.”

As alternate channels reduce the need for cash, allow remote or direct deposit of checks, or provide alternate outlets for obtaining cash, in-branch transaction activity (defined as the average monthly number of paying and receiving transactions) has eroded. Across the industry, median branch transaction counts have declined to 7,600 transactions per month, compared to 10,200 five years ago.

While the decline in transactions is significant, the magnitude varies by market segment. Branches in market areas with a high concentration of entry or affluent households have seen the most substantial declines, but many branches in areas dominated by mass market or seniors segments have experienced little (if any) erosion of in-branch transaction volumes.

A Conundrum Creating a Cross-Selling Culture

“The continued dominance of the branch channel for account opening seems to reflect the simple fact that consumers like branches.”

The branch reigns as the dominant sales channel. Irrespective of the use of the branch for transaction activities, the traditional branch remains the near exclusive venue for new account openings in all market segments. While average branch transaction volumes have declined by 25% during the past five years, branch-based new account sales have increased slightly, and more than 95% of new accounts are still opened in the traditional branch channel.

In an era in which consumers visit branches less frequently once they’ve established a banking relationship, it is imperative for institutions to cross-sell effectively in initial sales interviews. Yet despite decades of investments in sales training… despite nearly every bank and credit union CEO claiming a desire to “create a sales culture”… despite million-dollar customer relationship management (CRM) platforms… sales performance remains woefully inept.

“The median cross-sell ratio in banking is just 2.2 products per household, the same level as 15 years ago.”

Across the industry, the median cross-sell ratio is just 2.2 products per household. While that modest ratio is troubling, perhaps more damning is that 15 years and millions of dollars of sales culture investments ago, the median cross-sell ratio was 2.2 products per household.

Across the industry, about half of all relationships consist of only a single product, also unchanged over the past decade. So while transaction counts are diminishing, presumably allowing more time for customer conversations, institutions are not leveraging the additional time to improve relationship depth.

Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Vericast’s 2024 Financial TrendWatch explores seven of today’s most critical financial services trends to provide a complete view of the current loyalty landscape.

Read More about Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Are You Ready for a Digital Transformation?

Unlock the potential of your financial institution's digital future with Arriba Advisors. Chart a course for growth, value and superior customer experiences.

Why Do Branches Still Matter? Because Consumers Say They Do

“Despite the rise of alternate channels, location convenience remains the primary determinant of institution choice for consumers.”

Location convenience remains preeminent when consumers select a financial institution. In primary research interviews conducted for clients, Bancography invariably finds 45% to 55% of respondents saying “convenience of locations” is the main reason they selected their primary banking provider.

Recent research by the Federal Reserve Board corroborates this finding. In its Survey of Consumer Finances, a triennial survey of the financial behavior of American households, the Fed asks consumers to cite “the most important reason for choosing [current institution] for their main checking account.” In the 1992 survey, 44% of consumers cited “location of their offices” as the primary determinant. The proportion citing convenience never dropped below 43% in the next six iterations of the survey. In the most recent edition, it was 46%.

Probing further into the data reveals that the great majority of decisions are made through a filter that at least considers branch locations. Take for example consumers who are concerned about rates and fees. Ask consumers how they found out that their institution had the lowest fees, and the majority will expand their answer to reveal that the fees were the lowest available from convenient branches, not the absolute lowest fees. Consumers will look for the banks and credit unions in their neighborhood, then might call four or five branches to find the lowest rates and fees among them.

Banks Add Channels and Never Take Them Away

There has never been real channel replacement in banking. The ATM did not replace the branch. The call center did not replace the branch or the ATM. Internet banking did not replace the branch or the ATM or the call center. And mobile banking will not replace the branch or the ATM or the call center or Internet banking.

Each time the banking industry has given consumers a new channel, consumers have said “thank you, I’ll use that, too,” and simply reallocated their transactions among a broader array of channels. But almost every consumer reserves some set of transactions for in-person interactions. The institution that seeks to replace branches with digital channels is constraining consumer choices just as severely as the institution that offers only branches.

As Consumers Age, Channel Preferences Change

Preferences change over time. While younger generations have embraced alternate channels for transactional banking, that might not always be the case. A consumer who has little need for a branch in their 20s will have different needs and expectations as they age.

In midlife, financial needs grow more complex, necessitating direct interactions for questions. In later life, the reduction of time constraints and the social implications of an “empty nest” may create a social desire for personal interaction in business transactions, despite the availability of remote alternatives. Boomers were the first generation to adapt electronic banking channels in large numbers, but the leading edge of that generation is entering retirement and enjoying longer life expectancy than prior generations. Yet as declines in cognitive ability set in, won’t those aging retirees covet, demand and require in-person explanations of financial concerns?

The Network Effect

Larger branch networks capture disproportionate market share. An eight branch network will gain more than twice as much in deposits as a four branch network. Larger networks outperform smaller ones even on a per-branch basis. This relationship holds in markets of all sizes, as convenience-seeking consumers gravitate to perceived ubiquitous networks.

This “network effect” supports the argument in favor of dense branch networks concentrated in a few markets rather than toehold presences in numerous markets — i.e., depth over breadth. This especially holds for smaller banks and credit unions seeking to compete against the market-wide networks of regional and national banks.

As consumers reward convenient institutions, each successive branch provides an incremental lift to the other branches in the network, providing strong rationale for increased branching.

Note that the consumer preference for institutions with broad branch networks does not imply that consumers actually use numerous branches of those institutions; in fact, most consumers use no more than two branches of their primary provider.

Why Industry Cloud for Banking?

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking helps deliver personalized products and services that today’s customers expect.

Industry Cloud for Banking from PwC

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking applies our deep industry knowledge to your specific business needs

The Path Forward: A Prescription for Effective Branch Networks

New digital channels provide a means of reducing transaction costs, improving the customer’s overall service experience, and positioning an institution as forward thinking and technologically astute. But these channels require significant investments in both capital and non-interest expenses, creating pressure to reduce cost elsewhere in the delivery network. The obvious candidate for cuts: branches. But eliminating branches can prove detrimental to an institution’s growth.

Banks and credit unions must meet their customers across all channels and can do so with proper realignment of the branch network by considering the following options:

Embrace, Don’t Replace Branches. Ask any community bank or credit union executive what differentiates their institution, and inevitably you’ll hear “our people.” And if the quality of service those people deliver is truly a differentiator, then institutions should seek to maximize contact between their people and their customers. Financial institutions should value the face-to-face interactions that occur in their branches every day.

Less Transactions, More Interaction. Transactions cost money, sales earn money. The more of the latter and the less of the former, the more profitable the branch will become. Banks and credit unions should position their branches as venues where consumers can build a lifelong financial strategy, not just a place to cash a check. The goal is to encourage the use of alternate channels for routine transactions, not to exclude branches for more sophisticated inquiries. Banks and credit unions should promote branch visits as an integral part of a customer’s financial routine. Advertising and messaging should remind customers of the convenience of an institution’s branches and their ability to provide expert guidance on a broad array of borrowing, savings and investing challenges

Eliminate Full-Time Tellers. In all but the busiest branches, retail financial institutions should eliminate the full-time teller position. But in branches with lower transaction volumes, a teller may experience significant idle time, when no customers are in line in the lobby or the drive-in. Financial institutions can not afford to pay for that slack time with a teller tethered to the teller line, unable to perform other functions. They must adopt universal agent staffing models, in which cross-trained employees perform the functions of both tellers and customer service representatives, gravitating from one role to the other as needed.

CRM Must Become a Reality. The reduction in in-branch transactions represents a gift to financial institutions, as profitable sales activities can supplant costly transaction processing. But to leverage this benefit, the industry needs to improve cross-selling skills and migrate beyond the basic needs- assessment checklist to true consultative selling, delivering holistic advice for consumers in the lifelong management of their financial portfolios.

Be Flexible. “One size fits all” branching is not effective, especially as increasing competition divides many top markets into ever-smaller slices. In actuality, there is a service model that could prove profitable in just about any type of market. Financial institutions need a portfolio of service models — their own unique combination of branch sizes, technologies and staffing. Then, in any situation, an institution can select the service model that best aligns with specific market opportunity for each branch.

Think Small. Retain financial institutions need to test smaller branch configurations. This includes self-service branches with image-enabled ATMs and direct call center phones, cashless kiosk formats with attendants to open accounts and fulfill basic service requests, virtual branches with videoconferencing to customer service specialists, bank-at-work formats, and other small footprint, light staffed options. Ultimately, the goal should be to maximize the number of delivery outlets within the context of profitability constraints. Smaller operating models make more locations feasible, carrying with it two ancillary benefits: increasing perceived convenience, which in turn, pushes the financial institution farther up the market-to-outlet share curve. Mathematically, two $20 million branches are equivalent to one $40 million branch if each delivers the same proportionate returns; the key is operating the smaller branch for half the expense level of the larger branch.

About Bancography

Bancography provides consulting services, software tools and marketing research to financial institutions to support their branch, product and brand positioning strategies. Bancography offers branch planning and network optimization services in addition to Bancography Plan, our market analysis and branch planning software tool. In support of our clients’ current operations, Bancography builds branch staffing models, provides product and profitability assessments, and performs primary marketing research to measure market awareness, brand strength, onboarding, satisfaction and attrition factors.