Financial institutions do not summarize important policies and fee information in a uniform, concise, and easy-to-understand format that allows consumers to compare account terms and conditions. It doesn’t necessarily take a study to come to this conclusion, but that’s precisely what the Pew Charitable Trusts did anyway.

Pew studied data from the 12 largest banks and the 12 largest credit unions as determined by their domestic deposit volumes — a total of 274 different checking accounts. The median length of bank checking account disclosure statements was a cumbersome 69 pages, with a range of 21 to 153 pages. For credit unions, the median length was better — 31 pages, ranging from 9 to 53 pages — but a far cry from a breezy read. Although shorter, Pew says credit union disclosures often do not include information that would allow a customer to compare account fees, terms, and conditions.

Are financial institutions deliberately trying to take advantage of people by confusing them? Some would say yes, while banks and credit unions might argue they are merely victims of legal obfuscation, a consequence of our society’s litigious zeal. Either way, consumers are drowning if financial legalese.

A research study conducted by UC San Diego found that the average U.S. citizen consumes 100,500 words of information daily, including email, messages on social networks and other online sources. That’s just over 200 pages of information every day. Giving consumers a 69-page disclosure is like asking them to give up one-third of their available reading time (34.3%). It isn’t going to happen, especially when you consider the average American reads around 250-300 words per minute. That means it would take around 2 hours and 18 minutes to plow through the typical bank’s checking disclosure document (just over an hour for credit union disclosures).

“If you sat down and read all the disclosures for everything you bought, own and use, it would take you over a year.”

Key Questions: You wouldn’t read a 69-page disclosure document, so why would you ask anyone else to? When was the last time you read one of those bulky, tedious legal agreements — your credit card contract, the conditions of your mobile phone service, or the SLA for software you installed?

If you had to sit down and do nothing but read all the disclosures for everything you bought, own and use, it would take you well over a year to plow through it all. Your refrigerator, car, phone, wireless plan, internet provider, Facebook, Twitter, medicines, kids’ toys, etc., ad naseum — they all come with a deafening volume of terms and conditions. How refreshing it would be for a financial institution to stand out among this bureaucratic din by offering consumers a simple and easy-to-read disclosure document. If a bank or credit union is looking to differentiate itself, it should look all the tools at its disposal. Disclosures are no exception.

Reality Check: Banks and credit unions can’t say they are listening to “the voice of the customer” while dumping ponderous legal mumbo jumbo in people’s laps. You can’t claim “consumer advocacy” or a “strategy of transparency” if you’re giving folks a mountain of disclosures to wade through.

Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Vericast’s 2024 Financial TrendWatch explores seven of today’s most critical financial services trends to provide a complete view of the current loyalty landscape.

Read More about Move the Needle from Attrition to Acquisition

Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Achieve a better return on your marketing investment. Leverage behavioral data and analytics to target the right customers with the best possible offers.

Read More about Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Today’s Checking Disclosures Riddled With Issues

Pew says varying fee names and disclosure designs make it very difficult to compare options and can create substantial obstacles for consumers. For example, one credit union stated that an account had “no monthly service fee,” but, in fact, had a “minimum balance fee” that was assessed monthly unless the customer’s balance was above a certain threshold. This fee appeared to be functionally identical to a monthly service fee, but the use of different terms has the potential to mislead customers.

“You can’t claim ‘consumer advocacy’ or a ‘strategy of transparency’ if you’re giving folks a mountain of disclosures to wade through.”

Consumers also may be confused by the inclusion of fees or terms that apply exclusively to legacy accounts. As banks acquire other banks, account policies from the old bank are often “grandfathered in” for that bank’s accountholders. As a result, fees and terms may be added to fee schedules and account agreements that are not applicable to new accounts. Standard disclosures for each type of account offered could lessen this confusion.

These issues are exacerbated by the sheer number of different fees that a customer may encounter. While Pew identifies and discusses 12 fees that are common and central to checking accounts, the median number of additional service fees charged by banks was 26, and some accounts listed as many as 48. The median number of additional service fees charged by credit unions was 18, and some accounts listed up to 29.

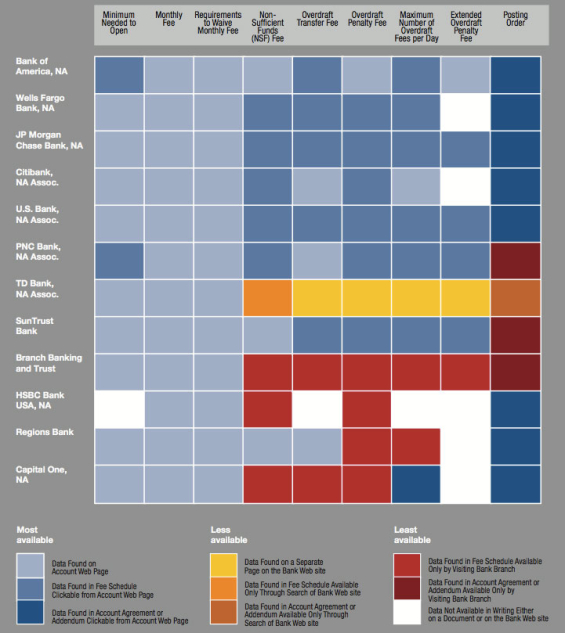

Problems Finding Disclosures at Banks

Pew also evaluated the location of the disclosures for certain fees and rules — or if they were disclosed at all. In some cases, terms and conditions were accessible on the institution’s checking home page or the Web pages of specific accounts, making them accessible to consumers. Information also could be accessed in fee schedules and account agreements available from the financial institutions’ websites. However, in other instances, details were not disclosed in any of these online locations, requiring customers to visit bank branches in person or request disclosure documents by mail.

Uniform disclosure of overdraft fees and terms would be especially helpful to consumers. At this point, however, banks do not even provide this information in a clear and concise manner. Four of the 12 banks did not disclose the size of overdraft penalty fees on their checking account home page or on the Web pages describing specific accounts, nor did they make available this information on any fee schedule linked from these Web sites. Three banks in the study did not disclose online their fees for non-sufficient funds (NSF), and three banks omitted from their Web sites out-of-network automated teller machine (ATM) fees.

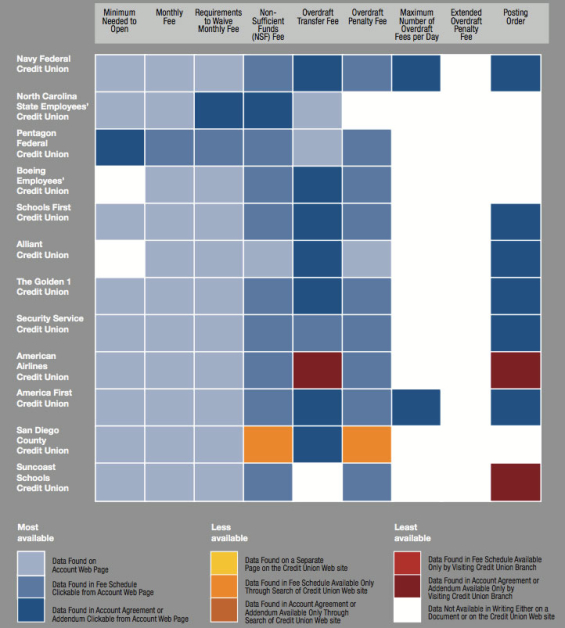

Problems Finding Disclosures at Credit Unions

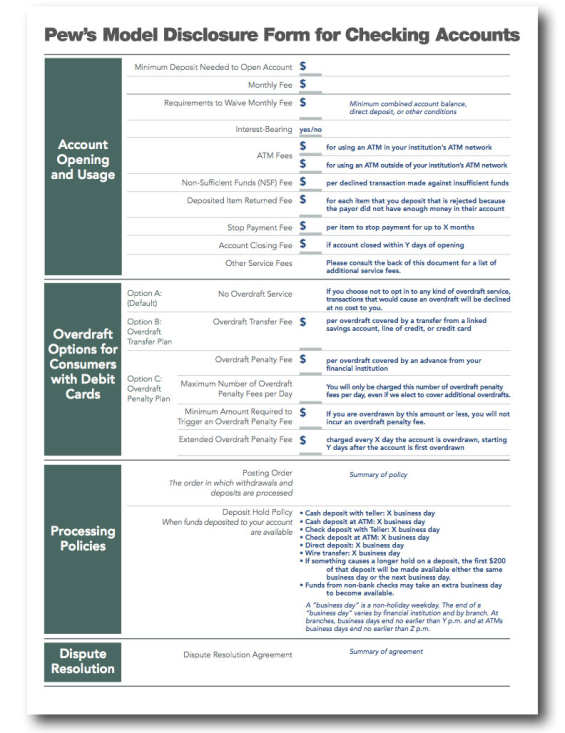

Pew’s Model Disclosure Box for Simplified Checking Accounts

Pew developed a model disclosure form, similar to a nutrition label for food or a Schumer Box for credit card offers. This model disclosure box would provide consumers with clear and consolidated information about the key fees, terms and conditions of their checking account. Researchers tested the disclosure box with consumers who said the box would be a useful and valuable tool when opening an account. The summary would also help consumers understand banking fees and important policies when comparing bank checking accounts.

Two senators are trying to turn Pew’s standardized fee disclosure form into law. Dick Durbin (D) and Jack Reed (D) are pushing for more transparency from banks, specifically with respect to fees and how they are disclosed.

“We’re calling all of the nation’s financial institutions to adopt a one-page, easy-to-read model disclosure listing the fees and key terms for their checking accounts,” Durbin said. “Giving consumers information clear, upfront and accurate information about the fees that they will be charged will allow consumers to shop around and make sound financial decisions.”

The duo also sent a letter to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau with a request that banks be required to post simpler disclosures on their websites.