Wells Fargo’s $3 billion settlement with the Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission under a “deferred prosecution agreement” is intended to finally allow the megabank to put its sales scandal behind it. But while the signatures were barely dry on the document, further potential reputation damage reared its head as a key congressional committee announced a trio of hearings that promised to produce a fresh round of Wells bashing.

The February 2020 settlement announcement by the bank and the federal agencies might have seemed like the last act in the main drama. Continuing waves of bad publicity and penalties began in 2016 when wide attention surfaced concerning fake and fraudulent sales of products by Wells employees, done in an effort to meet increasingly stringent sales goals.

The settlement follows closely on the late January 2020 announcement by the Comptroller of the Currency concerning major legal actions with eight former Wells Fargo leaders who served during the period of the bad practices. This included a settlement with former Chairman and CEO John Stumpf that carried a $17.5 million civil money penalty and his personal banishment from further involvement in banking.

After the Justice Department and SEC released the settlement, House Financial Services Committee Chairwoman Maxine Waters (D.-Calif.) announced that in March 2020 her committee would reveal the results of its yearlong investigation of Wells Fargo’s compliance with a series of regulatory orders that had been issued in the wake of the sales scandal.

The committee will hold three hearings in March under the theme of “Holding Wells Fargo Accountable.” One will look at “CEO Perspectives on Next Steps for the Bank that Broke America’s Trust,” featuring Wells’ new CEO and President Charlie Scharf. The next, “Examining the Role of the Board of Directors in the Bank’s Egregious Pattern of Consumer Abuses,” will hear from Elizabeth Duke and James Quigley, chairs of the parent company and the bank, respectively. The third hearing is titled “Examining the Impact of the Bank’s Toxic Culture on Its Employees.” (Subsequent to this article’s initial publication, on March 10, 2020, both Duke and Quigley resigned their board posts. Both still testified before the committee on March 11.)

“This fine barely dents Wells Fargo’s $200 billion in profit over the last ten years,” Waters said in a statement. “In short, this fine, which is coupled with a deferred prosecution agreement, is the cost of doing business for a bank with $1.9 trillion in assets. Wells Fargo must be fully accountable to the public for its crimes.”

Notably, the 12-page deferred prosecution agreement acknowledges the government’s expectation of the bank’s assistance in any prosecution of individuals connected with the unethical sales practices.

The case continues to offer fresh lessons for financial institution sales and marketing directors. These range from the realistic setting of sales and promotion goals to the balance between plain and careful disclosure and promotional speech in such documents as annual reports.

Unlocking Digital Acquisition: A Bank’s Journey to Become Digital-First

This webinar will offer a comprehensive roadmap for digital marketing success, from building foundational capabilities and structures and forging strategic partnerships, to assembling the right team.

Read More about Unlocking Digital Acquisition: A Bank’s Journey to Become Digital-First

Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Achieve a better return on your marketing investment. Leverage behavioral data and analytics to target the right customers with the best possible offers.

Read More about Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Big Legal Worry Ends, But the Fed’s Growth Limit Remains

The settlement, agreed to by the bank and the government, is perhaps the biggest milestone reached since Charlie Scharf, formerly CEO of Bank of New York Mellon, came over to Wells in late October 2019. As announced, it is intended to resolve the two agencies’ investigations into the sales practices and related actions of the bank’s Community Bank organization.

In a statement, Scharf said: “The conduct at the core of today’s settlements — and the past culture that gave rise to it — are reprehensible and wholly inconsistent with the values on which Wells Fargo was built. Our customers, shareholders and employees deserved more from the leadership of this company.”

Scharf noted that the settlement was the latest of many steps taken to remediate the bank’s errors.

“Over the past three years, we’ve made fundamental changes to our business model, compensation programs, leadership and governance,” he said. “While today’s announcement is a significant step in bringing this chapter to a close, there’s still more work we must do to rebuild the trust we lost.”

Added Scharf: “We are committing all necessary resources to ensure that nothing like this happens again, while also driving Wells Fargo forward.”

Moving forward is the key challenge, with a prime obstacle being Federal Reserve special oversight and limits on growth.

In a report issued the day of the settlement announcement, Keefe, Bruyette & Woods stated that “We believe an impending settlement was widely expected; still the settlement with the DOJ and SEC removes the overhang of these investigations. The fact that the fine is fully reserved for is a positive; however, in the end the Fed’s consent order remains the bigger overhang on shares of Wells Fargo & Co., in our view.”

The settlement actually consists of three agreements, one concerning the Justice Department’s criminal investigation, another its civil investigation, and one the SEC’s civil investigation. $500 million of the $3 billion penalty goes towards a “fair fund” to be administered by SEC. Fair funds are used by the agency to distribute returns of wrongful profits and portions of penalties to investors.

In exchange for the penalty and admission to numerous actions detailed in the settlement documents, Wells would put this behind it, legally and subject to conditions in the deferred prosecution agreement. Among the latter is continued cooperation with the government in pending investigations of individuals in connection with the controversial sales practices. Any resulting suits or settlements would raise the entire history of the sales practices affair all over again, of course.

Read More:

- Aggressive Cross-Selling Could Get You Banned from Banking for Life

- Get Over Wells Fargo Already and Start Cross-Selling Again

- Banking on the Hard Sell: How Cross-Selling Can Kill Your Culture

- There’s a Better Answer Than Sales-Based Incentives

Documents Provide Overview of Years of Admitted Abuse

The settlement agreements released by the two agencies cover much the same ground. However, the issues each is interested in differ somewhat.

“Wells Fargo admitted that it collected millions of dollars in fees and interest to which the company was not entitled, harmed the credit ratings of certain customers, and unlawfully misused customers’ sensitive personal information, including customers’ means of identification,” the Justice Department stated.

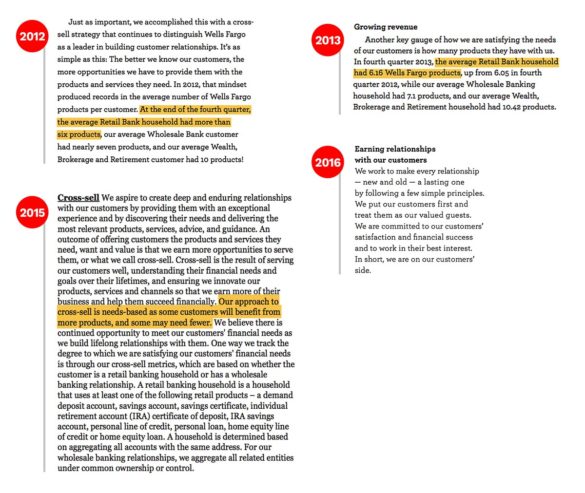

The settlement documents recount a history over the years of Wells’ leadership continually ratcheting up cross-selling targets, especially in retail banking product areas. Managers and employees came under increasing pressure to produce sales to make the numbers.

As recounted by case papers and other documents, the emphasis was on cross selling, even if the accounts brought in through the effort didn’t turn out to be profitable or even active. This led to frontline staff “gaming” the Wells system in numerous ways detailed in the government papers. In some cases consumers were misled in order to get them to open additional accounts. Often accounts were opened for consumers without their knowledge.

“Many widespread forms of gaming constituted violations of federal criminal law,” the Justice Department observes in its documents. Some examples cited:

• “Simulated funding”: Additional deposit accounts opened in consumers’ names but without their knowledge had to have some money in them to count. So consumers’ funds were transferred without their knowledge from other Wells accounts. In other cases, employees used funds of their own, temporarily, to fund the fake accounts.

• Forgery: Some employees were creating false records and forging consumer signatures to put through phony accounts. Where debit cards were issued without consumer approval, some made up fake personal identification numbers. “Employees often did so because the Community Bank rewarded them for opening online banking profiles, which required a debit card PIN to be activated,” according to case documents.

• Changing contact information: “Employees at times altered the customer phone numbers, email addresses, or physical addresses on account opening documents,” federal papers state, in some cases to avoid the consumer learning about the fake accounts opened in their name. sometimes employees used their own home addresses or input Wells Fargo email addresses.

As portrayed in the case documents and elsewhere, internal investigations began turning up evidence of employees faking account openings or gaming the system, but the company’s watchdogs were not always heeded. One internal investigations manager quoted in the papers said he wanted the community bank division’s leadership “to be constantly aware of this growing plague.”

In time, between 2011 and 2016, according to the documents, tens of thousands of Wells employees were accused of gaming the system. Over 5,300 were fired and many more were either disciplined but not terminated, or quit before matters were resolved.

“Almost all of the terminations and resignations were of Community Bank employees at the branch level, rather than managers outside of the branches or senior leadership within the Community Bank,” according to the papers.

Be Careful What You Claim in an Annual Report

The SEC’s function concerns investor protection specifically, and much of its part of the case concerns how investors were misled by management’s references in annual reports and other documents and conversations to the success of Wells Fargo’s cross-selling program.

Before its efforts were discredited, Wells’ cross-selling abilities were almost legendary, reaching ratios of services per customer that many other players could only aspire to.

The case documents note how often and how extensively Wells Fargo’s leadership team would talk up its cross-selling efforts and the results they were allegedly producing. The word “tout” is used multiple times to describe how much Wells made of this. In addition, the company frequently described its sales effort as bringing to consumers the products and services that they needed.

“In contrast to the company’s public statements and disclosures about needs-based selling,” the documents state, “the Community Bank implemented a volume-based sales model in which employees were directed, pressured, or caused to sell large volumes of products to existing customers, often with little regard to actual customer need or expected use.”

SEC pointed to both Wells’ failure to disclose the real nature of its cross-selling program as well as to the increasingly bogus reality behind the cross-selling metrics it was reporting and promoting.

“Wells Fargo publicly touted to investors the success of it’s Community Bank’s ‘cross-sell’ strategy — selling additional financial products to its existing customers — which it characterized as a key component of its financial success.”

Ominously for the beleaguered bank, an SEC news release noted: “The SEC’s investigation is continuing.”