Nine in 10 Americans have checking accounts. Unfortunately, the formal disclosure documents outlining these accounts’ fees, terms, and conditions are often long, unintelligible, and opaque. Overdraft and transaction processing practices often result in surprise fees. And dispute resolution terms leave little room for consumers to choose how they want to proceed in the event of a problem.

According to study by Pew Charitable Trusts, banks’ disclosure policies have improved, especially those related to overdrafts. With some regularity now, Pew has been examining how consumers are affected by the terms and conditions of checking accounts — with a particular focus on overdrafts — by reading, reviewing and analyzing account agreements to determine bank policies and practices. Pew’s latest report evaluates the practices of 44 of the 50 largest retail banks in the U.S. These institutions hold approximately 65% of all domestic deposits.

Improved Presentation of Disclosure Documents

More banks have adopted a summary disclosure box that highlights key terms — 43% in 2014 vs. only 22% in 2013. In fact, 26 banks and credit unions have worked with Pew to voluntarily adopt a model disclosure box for checking accounts, covering approximately 45% of deposits in the United States. At least six other banks have adopted a summary disclosure box that meets all of Pew’s criteria on their own. Some disclosure practices — such as identifying key overdraft information and fees — have universally improved, in large part due to the adoption of these summary disclosures.

In a separate study by research firm Which?, 18 volunteers were asked to calculate the total cost of overdrafts charged by the 12 biggest UK banks. Each of the volunteers were given a mock statement and asked to calculate the overall cost by finding the overdraft charges on a bank’s website. They then had to work out any interest charged and any fixed charges, like monthly or daily fees or penalties for unpaid transactions. Between them, they got just 10 of the 72 calculations correct. Across almost all the banks, the overall cost was so difficult to work out that even a principal inspector of taxes only got one of his four calculations right, and a retired headteacher got his answers all wrong. It also took an average of 10 minutes for volunteers to find where the charges where listed on the banks’ websites.

Read More: Consumers Want Banks to Dump All The Mumbo Jumbo

Fractional Marketing for Financial Brands

Services that scale with you.

Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

83% of FI leaders agree investing in AI is essential for 2024 but how you leverage AI is instrumental in success and meeting customer expectations.

Read More about Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

More Banks Are Making Their Disclosures Available Online

More banks make their account agreements and fee schedules available online than did in Pew’s 2013 study. In Pew’s most recent study, 12 banks did not make their information available online, and of these, six did not provide all the documents by mail or email when requested (yikes!). In our earlier survey, 20 banks did not provide their disclosures online, and 14 did not make them available in any medium when requested.

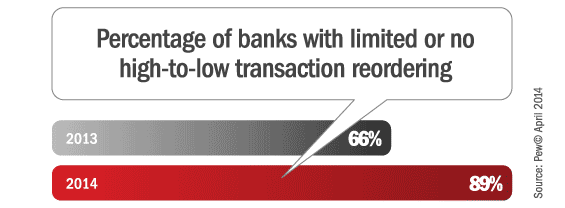

Deceptive ‘High-to-Low’ Transaction Reordering Remains a Problem

The percentage of studied banks that do not reorder transactions from high to low, which has the potential to increase a consumer’s overdraft fees, is virtually unchanged from last year. In 2014, 50 percent of banks abstain from this harmful practice. In 2013, it was 47 percent. Limiting this comparison to banks in both our 2014 and 2013 reports, the percentage abandoning this practice has grown by two banks, raising the share from 46 percent in 2013 to 51 percent in 2014.

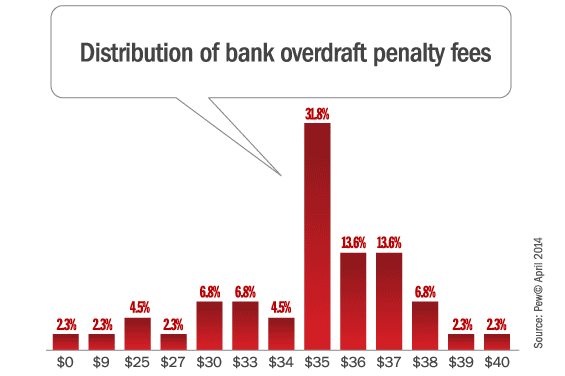

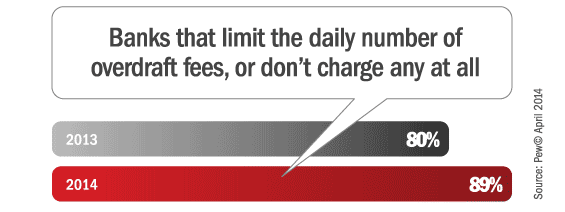

Detrimental Overdraft Practices Remain

Some overdraft practices have improved, such as including a threshold amount before an overdraft fee is charged and limiting the number of overdraft fees a consumer can incur in one day. Yet the same number of banks allow consumers to overdraw their accounts with their debit card at the cash register. And more banks are charging extended overdraft fees, which are incurred when the consumer does not pay back an overdraft loan and the fee within a certain number of days, usually five.

Little Change in the Number of Banks That Prohibit ATM Overdrafts

While the shift in the number of banks preventing ATM overdrafts remains fairly small — approximately one in five in 2013 and approximately one in four in 2014 — the impact on customers banking at institutions that have adopted this practice can be significant. The percentage of banks Pew studied that disclose they deny ATM withdrawals that would overdraw a checking account is virtually unchanged: 20% in 2014 compared with 19% in 2013.

Read More: More Banks Adopting Simplified Disclosures For Checking Accounts