In the United States, the banking industry generally loathes the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s public complaint database. But at least people have to go to the bureau’s website to view the complaints. In the U.K. the authorities decided to go one step further. Much further.

In the U.K., major banks must now publicize their ranking in an official survey. Notices must be posted on websites, in apps, and in branches — whether it means cheers, jeers, or tears.

Ratings good and bad must go right on the establishment’s front window. It’s like requiring restaurants in the U.S. to post their rating from the local health inspector, where anything less than an “A” grade is wholly unappetizing.

The regulatory measure evokes themes found in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s famous book about infamy, The Scarlet Letter, where public shame and humiliation is the price one pays for bad behavior. The losers in the U.K. ranking system are left with a big black eye that they can’t cover up. Indeed they are forced to advertise that their service sucks.

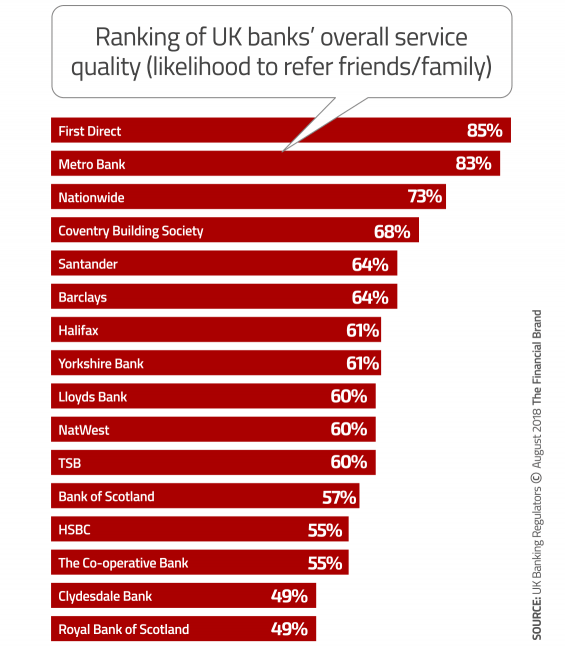

Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and Clydesdale Bank both had the unfortunate and dubious distinction sharing a tie for last place in the “Overall Service Quality” category. Both will have to tell the public that they rank dead last. U.K. regulators may as well be telling the two banks that they have to pour “customer-repellent” around their branches and in digital channels.

In the United States, several different private and nonprofit organizations publish rankings for the banking providers in various categories, and some banks and credit unions eagerly promote their status as a “best bank,” “best mobile app,” etc. That’s a great boost to marketing.

The U.K.’s government-mandated quality ranking system comes with regulatory and legal obligations. All financial institutions covered by the rankings system, which is administered by two different private market research firms using extensive surveys, must display the findings, no matter how well or poorly they placed. While some U.S. “best of” rankings permit companies to display decals or other objects for bragging rights, it would be unthinkable — even in these days where calls for “transparency” have become a battle cry — for any American institution to shout, “Hey, our service stinks!”

The closest thing you’d find to a government-sanctioned “shaming” in the U.S. would be an institution having a “Needs to Improve” or “Substantial Noncompliance” rating on a federal regulators’ public Community Reinvestment Act ratings report. And you’d have to really dig to find that. Every now and then, a major settlement reached between regulators and a financial institution requires the offender to express contrition and make amends publicly, such as the settlements reached with Wells Fargo over its various sales scandals.

Read More: Big Banks Take Beating in CFPB’s ‘10 Most Wanted’ List

Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

83% of FI leaders agree investing in AI is essential for 2024 but how you leverage AI is instrumental in success and meeting customer expectations.

Read More about Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

CFPB 1033 and Open Banking: Opportunities and Challenges

This webinar will help you understand the challenges and opportunities presented by the rule and develop strategies to capitalize on this evolving landscape.

Read More about CFPB 1033 and Open Banking: Opportunities and Challenges

Not Much To Brag About

In the annals of American marketing, bragging about anything but first place is not popular. Perhaps the only notable exception is the old Avis “We’re #2” campaign that explained why the car rental brand “tried harder” than their complacent competitor.

“We have more work to do to improve our service standards and deliver a better experience for customers.”

— Royal Bank of Scotland

But dealing with bad grades? Well, that’s a different matter.

The two bottom banks in the overall category took different approaches regarding their results.

Clydesdale Bank had very little to say publicly about its ranking, but RBS issued a statement:

“RBS welcomes any initiative aimed at improving transparency and comparability between banks’ performance on service quality. We are aware we have more work to do in order to improve our service standards and deliver a better experience for our customers. That is why we are investing in improving the products and services we offer our personal and business customers whether that’s through launching initiatives such as the UK’s first paperless mortgage or ESME, our digital lending platform for SMEs, which are helping us to deliver better service for our customers.”

RBS has taken its public lumps since the financial crisis, but the company’s net promoter scores (NPS) had been improving.

Indeed, the bank flagged NPS improvement in its 2017 annual report, but columnist Alistair Osborne of The Times took the occasion of the poor showing in the government rankings to poke a bit of fun. More seriously, he also commented that “The CMA has done us all a favour. … The new six-monthly surveys will produce national league tables of service quality that are far more useful than in-house scorecards. And they should help ‘drive up competition between banks,’ enabling customers to spot where they’re getting lousy service.”

(Of course, one might respond that favorable survey results don’t mean a hoot if individual consumers feel diddled by their providers.)

Osborne also pointed out that the survey results may make life harder on the U.K. Chancellor of the Exchequer — essentially the U.K.’s version of the U.S. Treasury Department. RBS, post-crisis, is partially government owned due to crisis-era capital injections, and the U.K. has been trying to sell those shares. As of mid-2018, it still owns more than half of RBS.

Read More: Managing Your Online Reviews Can Boost Customer Acquisition

How the U.K. System Works and How It Started

Over the last few years, British financial regulatory bodies have been paying increasing attention to the quality of service for both consumers and small businesses. The Competition & Markets Authority (the U.K.’s version of the FTC in United States) began digging into the delivery of banking services and, sometimes in concert with the Financial Conduct Authority, the principal national banking regulator. The two regulatory bodies took steps to increase both competition and transparency in the U.K. banking industry.

Consumer protection rules are nothing new to banks and credit unions in the U.S. But what makes the British government’s approach so unique is the pair of surveys underpinning this controversial new regulation: one dealing with consumer services, and one with business services. The surveys are conducted in England and Scotland, and a separate but parallel system is conducted for Northern Ireland. Surveys are to be updated twice a year.

In the consumer survey for England and Scotland, thousands of customers with “current accounts” (British for “checking account“) with the 16 largest providers were polled. Researchers asked them to rate their banking provider for each of the following: overall service, branch services, online and mobile services, and overdraft services. Institutions received points for consumers who were “extremely likely” or “very likely” to recommend them, no points for any other rating.

The rub? Institutions are required to pay for the cost to field these surveys.

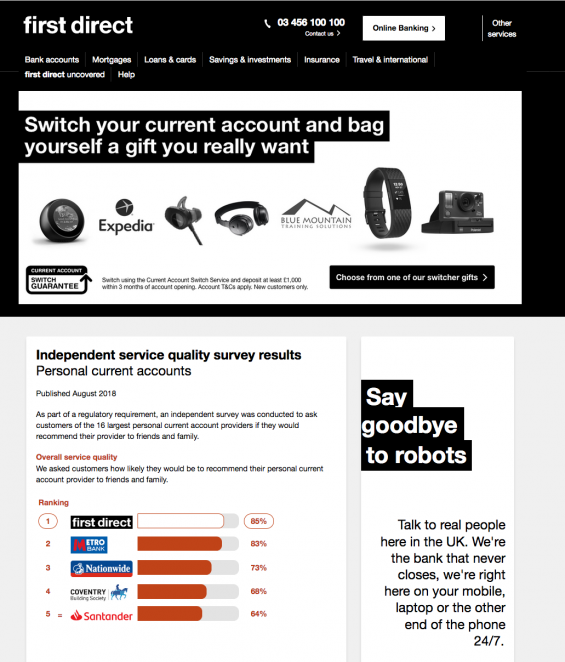

The first round of results came out in August 2018. In the overall consumer service quality rankings, First Direct, a U.K. online bank owned by HSBC, came in first, as well as first in the online and mobile banking services ranking. Metro Bank came in first for overdraft services and for services in branches.

“For the first time, people will now be able to easily compare banks on the quality of the service they provide, and so judge if they’re getting the most for their money or could do better elsewhere,” comments Adam Land, a senior CMA official.

Reality Check: Every bank in the U.K. surveys could have stellar scores, but “last place” is still going to look bad when the “loser” has to publicly disclose their ranking. It doesn’t matter if they got an “A” grade; this is truly grading on a curve.

Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Achieve a better return on your marketing investment. Leverage behavioral data and analytics to target the right customers with the best possible offers.

Read More about Send the Right Offers to the Right Consumers

Why Industry Cloud for Banking?

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking helps deliver personalized products and services that today’s customers expect.

How Institutions Published Their Ratings Online

U.K. rules require institutions to publish the top five institutions’ ratings, and, if they aren’t one of them, must add a sixth line showing their own ranking as well.

In branches, no notice needs to be visible from the outside, but inside the notice must be clearly visible to anyone coming in off the street. A standard piece of computer paper sufficiently meets the requirement — no large posters are mandated. Alternatively, electronic displays can be used to meet the in-branch requirement.

On websites, the information must be no more than one click away from the personal banking services page on the institution’s site, or no more than two clicks from the home page.

Some institutions put capsulized versions of the overall rankings right on their home pages. For example, First Direct bragged about its top ranking right on its home page. But so did Royal Bank of Scotland, who didn’t shy away from their last place finish on its home page, as well as others in the middle of the pack.

Metro Bank decided to promote both its consumer and business rankings with a press release — the only institution in the overall service listing to do so. The release points out that Metro is the only provider to rank in the top five for all qualifying business and personal services.

“As the survey results clearly demonstrate, Metro Bank creates fans,” states Craig Donaldson, CEO.

Similarly, Santander issued a release promoting its #1 overall business banking ranking in the Northern Ireland survey.

A whole other sector thus far has not been pulled into the survey rankings process. This includes the many “challenger banks” formed in the U.K. in recent years. In a blog, Starling Bank, one of those challengers, took the opportunity to crow about its own service quality, taking advantage of larger competitors’ exposure:

“As a new challenger bank Starling has not yet reached the threshold for publishing customer satisfaction scores, but with a user base growing at a rate of 20% a month, we soon will be. We can say with confidence that Britain’s challenger banks are outperforming incumbents when it comes to overall customer satisfaction.”

Starling went on to cite private surveys demonstrating that point, and to promise that as it grows, it will not give way to “complacency.”

Read More: The Challenger Bank Battlefield

Rankings In The U.S.

In the U.S., rankings for customer service have generally been the province of non-governmental organizations — J.D. Power and various national publications — and, with no legal requirement to post any result, the spin has always been on the positive.

Typically these rankings concentrate on larger institutions. Forbes this year partnered with market research firm Statista to publish rankings of the best banks and a separate listing of credit unions that concentrates on smaller players. These rankings come state by state, identifying names that never showed up on the other listings. Between one and five providers were identified as “best” in each state, with 124 banks and 145 credit unions making it into the Forbes rankings. As a group, credit unions averaged a bit ahead of the banks.

Here and there have been other attempts to rank institutions on service quality. In 2017, for example, Professor Ray Bresica of Albany Law School, and partners, unveiled a bank ranking based on 20 consumer-focused measures. Institutions in the New York Bank Ratings Index’s top ten places were either megabanks or large regional players. The project only looked at the 19 largest banks by assets operating in the states. Brescia says the hope is to conduct these ratings at least “semi-regularly.”

The likelihood of the federal government following in the U.K.’s path anytime soon is slim. Acting CPFB Director Mick Mulvaney isn’t a fan of the complaints database — to put it mildly. Indeed, he doesn’t really care much for the bureau that he oversees. And traditionally federal regulators have bent over backwards to avoid even the appearance of endorsing anything beyond necessary regulatory approvals of applications and proposals.