In the context of a (mostly) friendly debate during a banking conference, it’s fine for the CEO of a fintech startup to say “banks have already lost the game” — as one did recently (despite the fact that his firm’s strategy is to partner with banks). There are no facts or logic to back up that statement, but you gotta say what you gotta say to win a debate. My misplaced comment regarding “the British are coming!” is a not-so-shining example.

But if you’re going to make claims and predictions about banking with the intent to influence public and regulatory policy, you need to support your argument with data, logic, and reasoning. And therein lies the problem with a lot of the fintech hyperbole being thrown around: The absence of facts, logic, and reason.

TIME recently ran an article titled Banks Are Right To Be Afraid of the FinTech Boom. The article is rife with unsupported claims and contradictions. Below are direct quotes from the article, along with “my take” on them.

The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Learn how to enhance your brand’s local visibility, generate more leads, and attract more customers, all while adhering to industry regulations and compliance.

Read More about The Power of Localized Marketing in Financial Services

Why Industry Cloud for Banking?

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking helps deliver personalized products and services that today’s customers expect.

Where are Christopher Robin and Barney Fife When You Need Them?

TIME: “Policymakers should take steps to ensure that all Americans have access to secure, functional, and affordable financial services, as these commodities are crucial to financial wellbeing. But in absence of policy action, the market has moved to fill the need.”

My take:

If “the market has moved to fill the need,” then why should policymakers take more steps? Two words should come to mind when considering the impact of Dodd-Frank: Unintended consequences.

Christopher Robin and Barney Fife could have come up with more effective regulations for the banking industry.

It is not a given that policymakers should be ensuring that all Americans have access to “secure, functional, and affordable financial services.” What does “access” mean? I’m not aware of any Americans who don’t have “access” to banking services, although there are some who choose to not avail themselves of those services, and some who don’t qualify for some of them. Maybe what policymakers should focus on is helping those who don’t qualify improve their qualifications.

It is also not a foregone conclusion that these services are “crucial” to financial wellbeing. That said, I actually wouldn’t argue too vehemently against it. But I would argue vehemently that traditional financial services providers don’t necessarily have to be the ones who should, or have to, provide these services.

The idea that providers like check cashing services and payday loans are inherently evil and destructive is wrong, and wrong-headed. I wouldn’t be surprised if the customers of these so-called alternative providers are actually more satisfied than the customers of many so-called mainstream providers.

Is FinTech Enroaching — Or Collaborating?

TIME: “FinTech offers users an array of financial services—from transactions to underwriting—that were once almost exclusively the business of banks. Personal finance apps like Acorns, Digit, and Mint help users track their spending and stay on budget without the assistance of a financial advisor. Personal lending innovators like Lending Club and Prosper enable users to bypass traditional intermediaries with a peer-to-peer lending platform. Companies like Betterment and Wealthfront that facilitate investments, financial planning, and portfolio management have emerged as popular alternatives to traditional wealth managers.”

My take:

I’m struggling with the assertions here. Digit puts money into traditional banks. Mint survives because traditional financial services providers advertise on the platform. Lending Club might “enable users to bypass traditional intermediaries,” but 83% of Lending Club borrowers use the funds to pay off loans and credit card debt from traditional intermediaries. The statement about Betterment and Wealthfront isn’t exactly accurate. These two firms tend to serve investors whose assets don’t reach the level that make them good candidates to be customers of traditional wealth managers, so they aren’t really “alternatives.”

Profit Sappening Not Happening

TIME: “While FinTech is booming, it’s unlikely to replace banks altogether, and many FinTech companies actually rely on existing bank accounts. But it is sapping away the banking sector’s profitability, which has raised concerns among traditional banks about their capacity to maintain low-margin services and in a rapidly changing marketplace.”

My take:

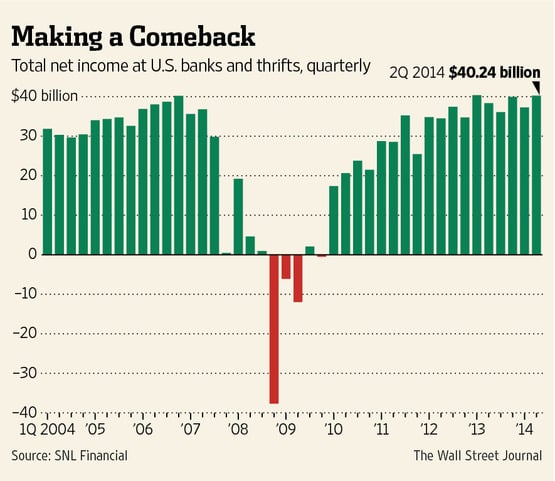

There is no evidence that fintech is “sapping” the banking sector’s profitability, let alone having any impact. As the following chart shows, profits have rebounded nicely since the depths of the financial crisis. Granted, the rebound in ROE still leaves that metric below historic highs, but you’re going to have to try a lot harder to make the connection that fintech is the cause of that shortfall.

Extraction Retraction

TIME: “Generally, banks follow a loss leader pricing strategy: They provide certain products (checking accounts) at a cost below their market value to stimulate the sales of more profitable products (loans) and to attract new customers. Now FinTech companies are extracting the most profitable portions of the banking model, leaving banks stuck with high overhead and less profitable products.”

My take:

Fintech companies are “extracting the most profitable portions of the banking model”? Got proof? Of course not, because it isn’t true. Actually, it’s not even debatable because the statement is meaningless. Different types of financial providers reap profits from different segments of the market. So there is no singular “most profitable portion.”

Recoup D’Etat

TIME: “To recoup their resulting market losses and mitigate the threat of FinTech insurgents, traditional banks and other legacy players in the financial sector are discussing a range of strategies, including charging more for low-margin services, closing bank branches to cut costs, and acquiring FinTech companies. Unfortunately, the impact of some of these strategies has the potential to disrupt the financial lives of low-income households. The worst-case scenario for low-income families if FinTech’s drain on their profitability prompts banks to abandon their loss leader strategies. For people at the margins of the financial mainstream, the loss leader strategy is a financial lifeline that enables them to maintain checking and savings accounts.”

My take:

1) “To recoup their resulting market losses”? What losses? You just saw the profit rebound. From Q1 2009 to Q1 2015, the 10 largest Internet banks grew deposits by a little more than $175 billion. Whoa! Disruption? No. The three largest US banks grew their deposits by $1.27 trillion over that period. The rest of the legacy banking world — banks and credit unions — grew deposits by $1.66 trillion. Recouping market losses, my foot.

2) If the unbanked don’t have accounts with banks, how could banks’ actions to charge more, close branches, and acquire FinTech companies be harmful and disrupt the financial lives of low-income households?

3) If fintech startups were truly “draining” the profitability of large/traditional banks, then acquiring the startups would theoretically boost the profits of the larger banks, thereby improving the lives of low-income families.

4) The notion that “the loss leader strategy is a financial lifeline that enables them to maintain checking and savings accounts” is ludicrous. If banks raise their fees (thereby abandoning the “loss leader” strategy), there is no shortage of credit unions that still offer free checking.

The passage cited above may very well contain the most-egregiously incorrect statements in the whole article. And that’s saying a lot.

Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

83% of FI leaders agree investing in AI is essential for 2024 but how you leverage AI is instrumental in success and meeting customer expectations.

Read More about Navigating the Role of AI in Financial Institutions

Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

Build a modern credit card strategy that balances profitability and risk, adopts the latest technology and delivers the customization that cardholders demand.

Read More about Navigating Credit Card Issuing in an Uncertain Economic Environment

History Hysteria

TIME: “If the threat to their business grows, banks could opt to use their superior resources to buy up FinTech companies. With the five biggest banks controlling nearly $15 trillion in assets, FinTech’s $12.4 billion in venture investments this year look like peanuts. While usurping the threat of FinTech by co-opting it may relieve immediate pressure on the banks, it won’t necessarily stop them from trying to cut costs in other ways that disproportionately impact those at the bottom rung on the income ladder. With the last 50 years of history at our backs (or even just the last 10), do we really want banks annexing every potential rival?”

My take:

1) The idea that cost-cutting initiatives are aimed at — let alone disproportionately impact — lower-income consumers is, once again, not supported by any facts or logic.

2) It’s just as appropriate to ask: With the last 7 years of history at our backs, do we really want the government wasting more effort and taxpayer dollars on misguided, wrong-headed, counter-productive initiatives and regulations that harm the people they think they’re helping?

The last 50 years of history tells us that the banking industry: a) made credit available — through mortgages and credit cards — to millions of people enabling them to buy homes and other things they wanted/needed, and b) has continuously introduced innovations like ATMs, online banking, online bill pay, mobile banking, remote deposit capture, etc. that have improved the banking experience. None of this would have happened without the collaboration of banks and startups, and investments made by banks in startups.

The better question to ask here is: Do we really want the government choking off all innovation and progress?

3) The article contains an underlying assertion that all — or even many — FinTech startups are bank rivals. This reflects a lack of understanding of the financial services ecosystem, and the potential benefits to startups of leveraging legacy banks’ market positions. For facts to back this up, take a look at the recent partnerships between Lending Club and banks, or USAA’s $40 million investment in MX. How are these bad for lower-income consumers?

Going Postal

TIME: “Policymakers should be designing and supporting ideas that promote more financial inclusion, whether that means more community credit unions, subsidies and tax credits for financial services, or a government-run option like postal banking.”

My take:

I’m struggling a bit with the assertion that creating new community credit unions would somehow alleviate the inclusion problem. Maybe someone could explain that one to me.

As for the idea of postal banking, let’s again try to inject a little logic and reasoning into the discussion.

The author states that “one in three unbanked households reported high or unpredictable account fees as a reason for not owning an account.” If it were profitable for banks to serve these households at lower fee levels, I can assure you that banks would reduce their fees. Now, if banks can’t profitably serve these customers at below-market rates, what makes you believe that the US-run postal service could profitably serve them at those rates?

Reality: Simply having a vast physical presence is no guarantee of the postal service’s prospects for success in banking. Where’s the technology to support banking functions going to come from? Where is the customer support going to come from? Where is the risk management and security controls going to come from?

The level of investment needed to create and support a banking operation would be immense, and if you think the Unbanked — who account for just 8% of households in the US — are going to come flocking to the post offices to open accounts, you’re nuts. Right off the bat, half aren’t even likely to consider a postal service-run banking offering, because they’ve opted to manage their financial lives with prepaid debit cards.

Here’s a radical idea to counter the one in the TIME article: What if policymakers designed and supported ideas that increased the number and quality of jobs in the market, thereby reducing the number of people for whom we had to worry about “including” in the traditional banking market? A boy can dream, you know.

Bottom Line

There is no shortage of opinions on where the banking industry is headed, as well as where it should be headed. Stating your opinion on the matter is a good thing. Supporting your opinions with data, facts, logic, and reasoning will give your opinions a lot more credibility. Without them, you’re just spewing fiction, fallacies, and fantasies.

The TIME article is just that — fiction, fallacies, and fantasies. The article is troublesome, however, because it:

- Accuses banks of intentionally harming low-income consumers with their pricing policies and investment decisions (i.e., basically accusing banks of being inherently bad or evil);

- Positions FinTech as some monolithic construct that is all socially-beneficial, and that will someone how save us from the evils of the legacy banking industry; and

- Advocates for policy changes based on these misguided assumptions and attitudes.

Devoid of facts and logic, the prescriptions and warnings put forth in the TIME articles are irresponsible and counter-productive. The article is an example of the rapidly-increasing politicization of banking, where policymakers and policy influencers twist and conflate the role of banks in the economic structure, and seek to place blame for the perceived wrongs in the world.

There’s No Debate

Towards the end of the Great Debate (referenced at the beginning of this post), I suggested that the question at hand — Who would rule banking: fintech or banks? — was the wrong question to ask. There is no one or the other. Banks need fintech, fintech needs banks. And banks become fintech, as fintech become banks.

In many ways, fintech is a — or the — path to reinvention for many banks. This is why a Capital One acquires design firms, or a BBVA acquires a Simple. It’s not simply to acquire the technology, and certainly not to “usurp the threat of FinTech by co-opting it.” It’s to inject new thinking and new capabilities into the company.

Slowing down, or preventing, this reinvention with the policy prescriptions proposed in the TIME article doesn’t help anyone, and — just the opposite — harms the majority of consumers who are customers of the legacy banking world.