Banking acquitted itself well during the real-life “stress test” of the 2020 pandemic year. That fact isn’t acknowledged often enough. The overall response was impressive at all levels and the industry and its two-million-plus employees can feel justifiably proud.

But in business, as in all other human endeavors, all glory is fleeting. The Covid experience had a lasting impact on banks and credit unions in almost every aspect of their business. So far, dire predictions of massive business and consumer defaults have not materialized, thankfully. Also, the widely discussed idea that accelerated use of digital banking will cause the branch banking model to fade into history remains very much an open question. Branches continue to be pivotal to the business model of many institutions.

These and other broad trends impacting banking are covered in the banking industry outlook report released each year by bank research and consulting firm Bancography.

The first part of the 51-page report tells the tale of the pandemic’s impact through multiple charts and graphs. The second section, “The Challenges of the Post-Covid Era,” explores various trends unleashed (or amplified) by the pandemic and is followed by “Advice for the Year Ahead.” This article summarizes the key trends identified by the report, expanding on them based on an interview with Bancography’s President, Steven Reider.

Uneven Deposit Flood

The foremost impact on banking of the pandemic, from a balance sheet perspective was the skyrocketing growth in consumer and business deposits. This has left the industry with “immense liquidity” and few ways to use it given sharply reduced loan demand.

“Every top-30 market except San Francisco and New York posted at least 10% deposit growth in 2020 — stratospheric levels relative to historic norms,” the report states.

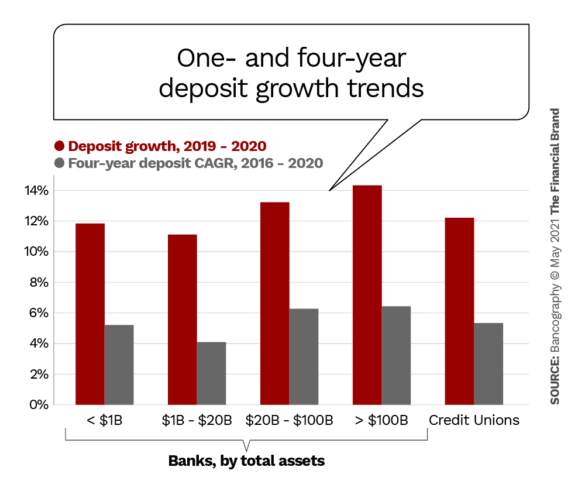

However, as can be seen below, the deposit growth was not evenly distributed by size or type of institution. Continuing an ongoing trend, the largest banks attracted the biggest share of deposits, with banks in the $1 billion to $20 billion “middle ground,” as Bancography calls it, lagging the rest of the industry.

Regarding credit unions’ comparatively strong deposit results, Reider observes that “credit unions, because of their nonprofit member-owned structure, are probably less able to turn down the spigot on deposits. So they ended up a little bit more liquidity-bloated than the banks.”

Read More: Why Bankers Won’t Ditch Branches, Despite Digital’s Explosive Growth

Industry Cloud for Banking from PwC

PwC’s Industry Cloud for Banking applies our deep industry knowledge to your specific business needs

How Banks Are Fortifying Their Data Against Increasing Cyber Threats

This webinar from Veeam will detail the value of working together across your organization to be better prepared in cyber defense and response readiness.

Read More about How Banks Are Fortifying Their Data Against Increasing Cyber Threats

Squeeze in Banking’s ‘Middle Ground’

Overall, Reider believes that financial institutions can expect to see some mitigation of excess deposits. Clearly consumers already are moving money back into the stock market, and based on rising bookings for airlines and Disney World, are starting to spend some of that spare cash.

This is good news for banking, especially if lending also picks up, but Reider expects the pressure on “middle-ground” institutions will not only continue, but increase. He views them as being much like department stores, which have been outflanked by Walmart, Target and Amazon — competing on the basis of relentless price and efficiency — on the one hand, and small local boutiques that thrive on personalized service on the other.

“In banking,” he states, “a $15 billion dollar bank doesn’t have the relentless scale for nationwide advertising of a BofA, Chase or PNC, but also is probably a little too layered to compete effectively with a good community bank.”

Further, the most advanced technology is so expensive today, he says, that it is beyond the budget of mid-tier institutions.

Read More: Banking Mergers: Bigger Isn’t Always Better

How the Merger Outlook Has Changed

This technology “squeeze” is a big factor driving mergers among financial institutions in that middle tier. Reider cites the South State/CenterState, First Horizon/Iberia and M&T/People’s United deals as examples of institutions looking to push north of $50 billion in assets to get technology scale.

But part of it also is pandemic-induced earnings pressure.

“Some of the pandemic relief programs masked bank earnings problems,” Reider maintains. “We didn’t have massive defaults because of mortgage forbearance programs and eviction moratoriums,” he states. But mortgage payments don’t go away with forbearance. They just get tacked onto the end of your mortgage. At some point, some credit challenges that have been hidden will manifest themselves, he believes. The Bancography report looks into this in some detail.

Another merger driver is the “strategic pick-up,” Reider points out.

“If you’re a mid-tier institution like Fifth Third,” he explains, “and you’ve got a major metro market where the leaders have 30 branches and you’ve got ten, it’s pretty appealing to buy a strong local community bank versus trying to build market share yourself.”

Beware of Linear Branch Predictions

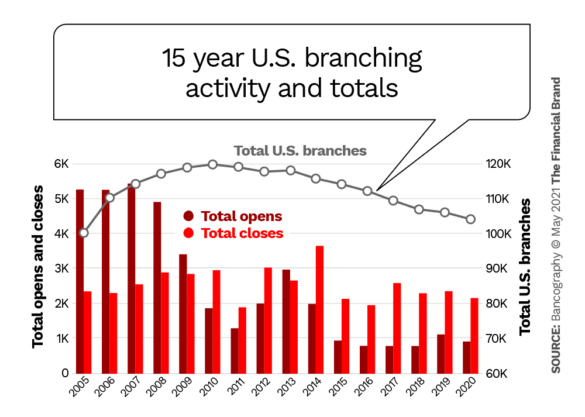

Bancography has a specialty in branch analysis. Last year’s report pointed out that given the sudden shift from branch to remote channels, banks and credit unions may need to accelerate branch contractions. Some did, but overall, the pandemic year did not turn out to be much different from the previous six years in terms of net branch closings.

“Certainly the pandemic changed the way people interact with their financial institutions,” Reider agrees. How durable that change will be remains to be seen, he adds. “One of the things we’re seeing is that consumers are very quickly reverting to their prior habits, which is why the pandemic may not bring the seismic change in behavior we initially thought.”

One reason for this is that the early adopters of digital banking — the “I don’t need a branch for anything” crowd — were gone long before 2020, according to Reider. The regular branch users who are left are small businesses, some seniors and some mass market consumers.

“Anecdotally, most of our clients are telling us that when they reopen lobbies, they’re seeing already an 80% bounce-back in transaction volumes.”

— Steve Reider, Bancography

In fact, a few credit unions the company works with are once again having branch congestion issues on Fridays.

The consultant agrees there is surplus in the system, but to say that the current rate of net branch decline is linear and will result in zero branches is not plausible, he maintains. Mergers will continue to reduce the overall numbers.

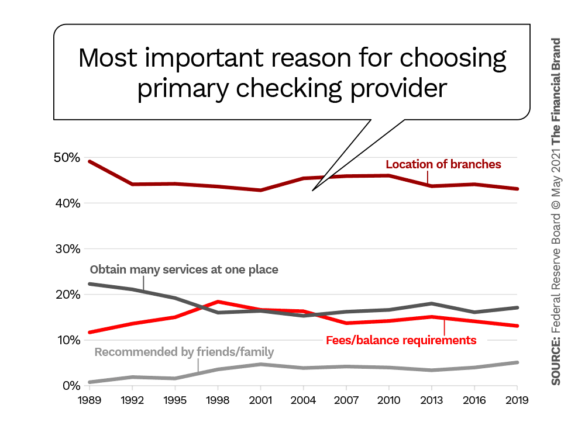

Federal Reserve data shows that 43% of people in 2019 still chose their primary banking provider on the basis of a nearby branch location. Based on his work with clients, Reider believes that percentage would not have changed much since then.

“I don’t think consumers see nontraditional bank alternatives as so superior to traditional institutions that they say, ‘Well, I should open an account digitally because it’s such a hassle to stop off at my branch’,” says Reider.

The absolute number of branches is less important than what proportion of American households live within X miles of a branch, Reider states.

Bancography’s most recent data found that there has been a slight increase in that distance. What’s happening there, Reider explains, is some bankers are saying, “You know what, we can tolerate a little more deposit-loss risk because we believe that with our electronic channels, consumers are willing to accept a little bit more spacing between branches.”

Once people open that account in branch, they may never be seen in the branch again, Reider agrees. And thus up-to-date digital product offerings are critical.

Zero Transactions Would Be Great

The Financial Brand asked Reider if, given the reduced traffic in branches, it was economically sustainable to have so many of them. He made two points in response:

First, banks and credit unions are paying a great deal of attention to the cost efficiency of their branches. They’re using interactive (video) teller machines, which help reduce head count, they’re shrinking branch footprints, and using cash recyclers to enable cross-trained universal bankers to provide service and also to roam.

Against the Grain:

It’s a mistake to fixate on declining branch transactions. A 50% decline is a good thing, if your new account openings are strong.

Second, Reider says, “If you separate what the branch does into revenue generating sales and cost generating transactions, to the extent that we lose the latter from the branches, that’s not a bad thing — in fact, it’s a good thing. We’ve seen anywhere from 35% to 50% decline in branch transactions over the past five years at most institutions. New account volume, though, really has not dissipated for most, and to the extent that it has, most institutions have been able to replicate that through their other channels.”

That’s good news for the majority of traditional financial institutions. But closely monitoring branch data and making appropriate adjustments will always be a critical exercise.

“To the community bank, the branch is the awareness indicator. Think of a world in which everybody banks only online. Who wins the day? It’s the one with the biggest advertising budget.”

— Steve Reider, Bancography

Read More: Community Bank Amplifies Niche Strategy Based on ROA/ROE Analysis

What’s the Key to Community Institution Survival?

Circling back to the technology issue, Reider points out a another challenge to smaller institutions, and offers a suggestion.

When Wells Fargo builds an in-house mobile application the fixed cost of that development amortizes downward with every new customer it adds, he notes. By contrast, smaller institutions that “rent” their technology typically pay X cents a month per customer and Y cents per transaction. So every time they add a customer, their costs go up.

So how do the “renters” overcome that disadvantage?

The answer lies not so much in how technology is used, but in adjusting their business model. If banking were in the pizza delivery business, Reider observes, they could compete on cost, speed of delivery or taste, or all three.

He says banks and credit unions should ask themselves, “What are the attributes we compete on?” Are we the low-cost provider or the gourmet pizza? Being all things to all people, however, is increasingly a tough road in banking for all but a few.

But low-cost is tough, too, because community institutions are not going to match the big guys on cutting-edge technology, according to Reider. So what other levers can they pull? He believes specialization is the answer.

“For years, we’ve said banking is a commoditized industry,” says Reider. He maintains that more community institutions will choose to specialize, and many already have. They’re choosing to cater to the emerging affluent, attorneys and accountants or any kind of professional services field, or they’re serving first-generation immigrant families with a selection of high-tech, low-cost products, or they concentrate just on business banking and are not consumer-oriented, or on mortgage lending.

Even some mid-tier institutions have successfully grown themselves out of competitive sameness with a specialty focus. New York’s Signature Bank is an example in the multi-family lending market.